Posted on: Monday July 15, 2019

Water-saturated bogs and burning hot, cactus-covered sand dunes are not the kinds of habitats that you would normally expect to find near each other. But on a recent trip to Canadian Forces Base Shilo, I was surprised to find just that!

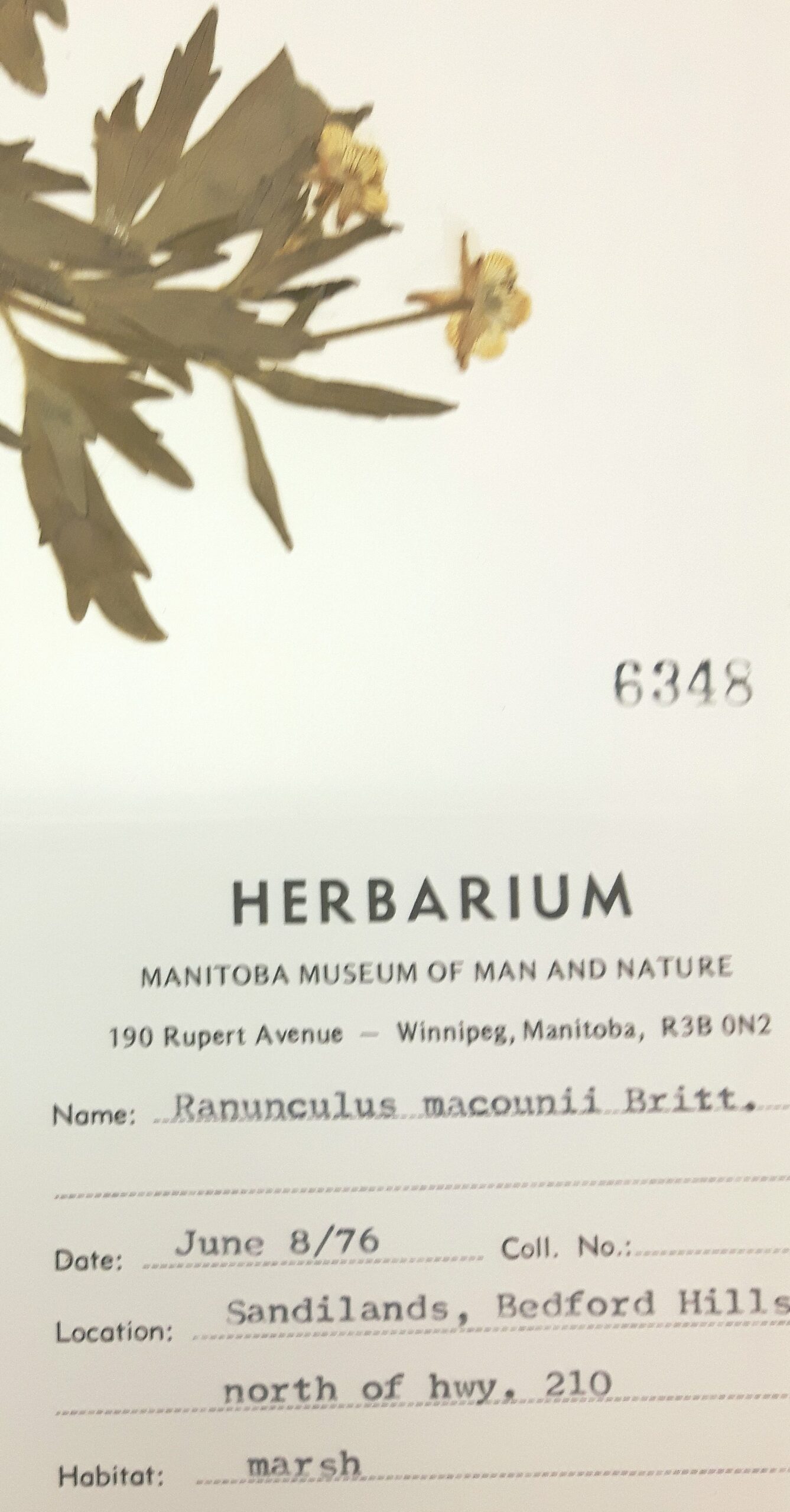

In July, I was able to visit this restricted area to collect plants as part of a research project. We went to a part of the base that I have never been to before: Sewell Lake. I was expecting the kind of vegetation that you typically find along a prairie wetland: cattails, sedges and bulrushes. What I discovered was an area that looked more like a bog in the middle of the boreal forest. Thick mats of moss floated on top of water and threatened to swallow you up if you weren’t careful. Aquatic plants like water calla (Calla palustris), buckbean (Menyanthes trifoliata) and marsh cinquefoil (Comarum palustre) lined the shore. Even pitcherplants (Sarracenia purpurea) have been found in the deepest areas of the bog. Turtles swam in the water and all sorts of amazing insects were everywhere. It was truly unusual and a biologists’ delight.

Water calla (Calla palustris) is usually found in northern lakeshores and bogs.

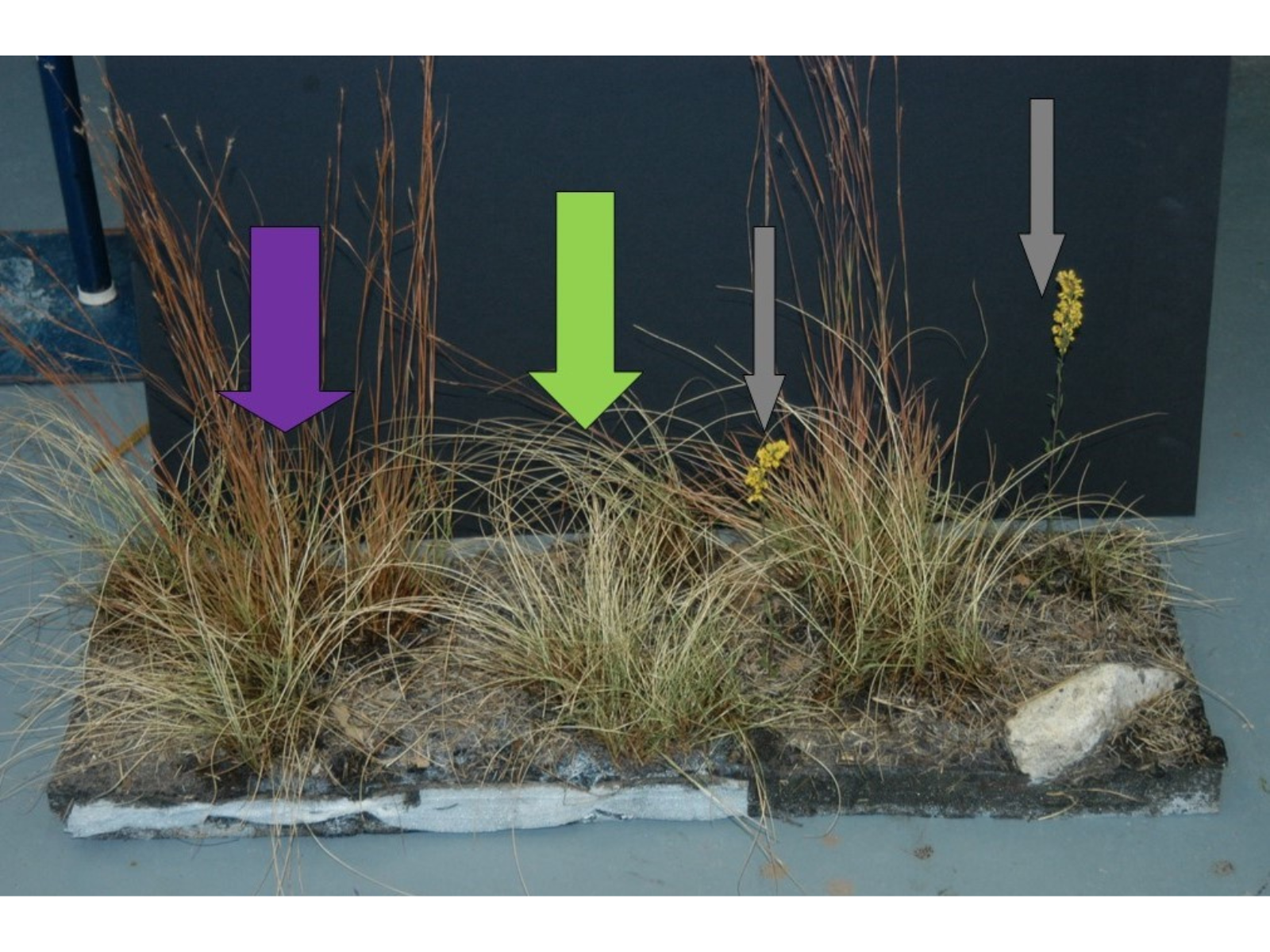

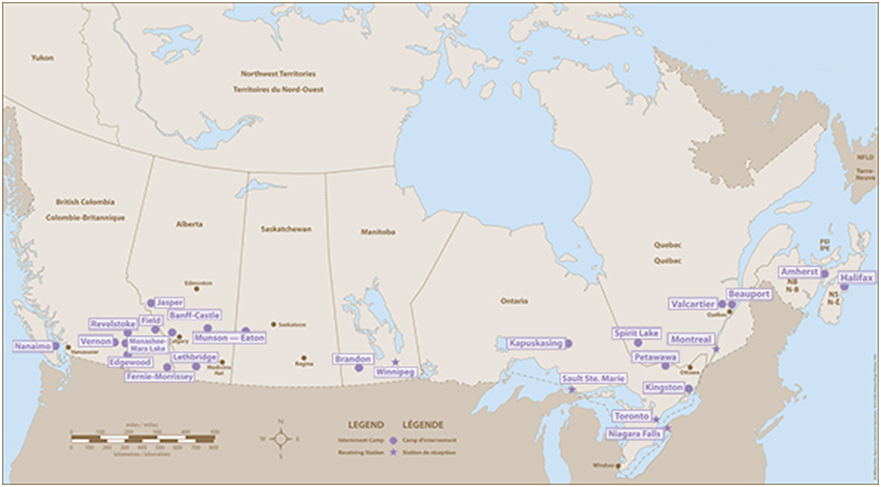

But what was the oddest thing was that not even 50-m away from this wetland there was a huge sand dune that ran parallel to the lakeshore. While walking along the ridge of this dune, I encountered rare plants that you only find on the driest of prairies: prickly pear (Opuntia fragilis), and pincushion cactus (Coryphantha vivipara), winged pigweed (Cycloloma atriplicifolium), American bugseed (Corispermum americanum), and the lovely hairy prairie-clover (Dalea villosa). Our guide told us that there are an astounding 450 species of vascular plants on the base lands, an impressive number when you consider that there are only just under 1700 plant species in the whole province.

Image: Fragile prickly pear cactus (Opuntia fragilis) is a highly drought tolerant species.

So, on the one side there were plants that were adapted to dealing with an excess of water and on the other plants that dealt with an almost complete lack of it. So how do plants deal with these conditions? They possess completely different internal structures. In wet habitats, the biggest danger to plants is a lack of oxygen. You’re probably puzzled. Don’t plants need carbon dioxide? Well yes they need carbon dioxide for photosynthesis, which occurs mainly in the leaves, but they also need oxygen to break down the sugars they create to obtain energy for growth. This isn’t a problem for leaves and roots living in soil with lots of air pockets but it is a problem in water-saturated soils. To get oxygen to the roots, many aquatic plants have special tissue called aerenchyma–tissue with big air tubes in it–which functions a bit like a snorkel. The plant moves oxygen from the holes in their leaves, called stomata, all the way through these tubes to the roots. Problem solved! Regular dryland plants don’t have aerenchyma, which is why over-watering your houseplants can kill them; they basically suffocate.

In contrast, for plants in dry habitats like sand dunes, obtaining and retaining water is the problem. To obtain water they either grow roots deep enough to reach the water table, or absorb water quickly when it does rain by growing extra root hairs. To prevent water loss, they may possess thick “skin” that prevents evaporation; cacti are a good example of this. As well, they can prevent evaporation of their water by keeping their air holes (stomata) closed during the heat of the day, opening them to obtain gases at times when it isn’t so hot.

For aquatic plants, not drowning is an essential skill!

Plants on dune ridges take a siesta from photosynthesis in the heat of the day.

The structural uniqueness of plants is not always appreciated, recognized or understood by non-botanists. But really the difference between plants in bogs and sand dunes is like the difference between a fish and a camel!