Did you know that these gutskin pants are completely waterproof? Learn more in this video with Dr. Amelia Fay, Curator of Anthropology & the HBC Museum Collection.

Did you know about this Mother-Daughter duo in Manitoba politics? #IWD2023

Did you know about mother-daughter duo Edith Rogers and Margaret Konantz? They were two Manitoban political powerhouses.

Learn more in this video with Anya, our Learning & Engagement Supervisor in honour of International Womens Day!

Did you know about Menelik Lodge No. 528?

Did you know that the Menelik Lodge was founded by the Winnipeg Union of Sleeping Car Porters to support the Black community? Many of the families that were part of the founding of the organization are still here in Winnipeg today.

Learn more with Roland Sawatzky, Manitoba Museum Curator of History, and Naomi Dennie, a teacher in Seven Oaks School Division and creator of the Amplify Us podcast, as they share more about Winnipeg’s “Elks”. Find more details in their recent blog post Menelik Lodge No. 528 here.

The Rogues’ Gallery of the Manitoba Museum

My first day at the Manitoba Museum began with a guided behind-the-scenes tour through the research labs, workshops, and collections storage rooms that are not accessible to the public. On a tight schedule, I got to see a little bit of everything, but when the tour was over I knew I needed to see so much more. Through the next week I found the time to explore the specimens of the Natural History collections room, starting with my favourite group of animals – the insects! The Museum’s insect collection contains fascinating specimens from Manitoba and beyond, sorted neatly by species into glass-topped wooden drawers which are stored in tall, sealed cabinets. In the course of my thorough investigation, I found amazing wasps, rugged beetles, and showstopping butterflies. Nothing, however, captured my imagination quite like the contents of one otherwise unassuming box simply marked “Museum Pests”.

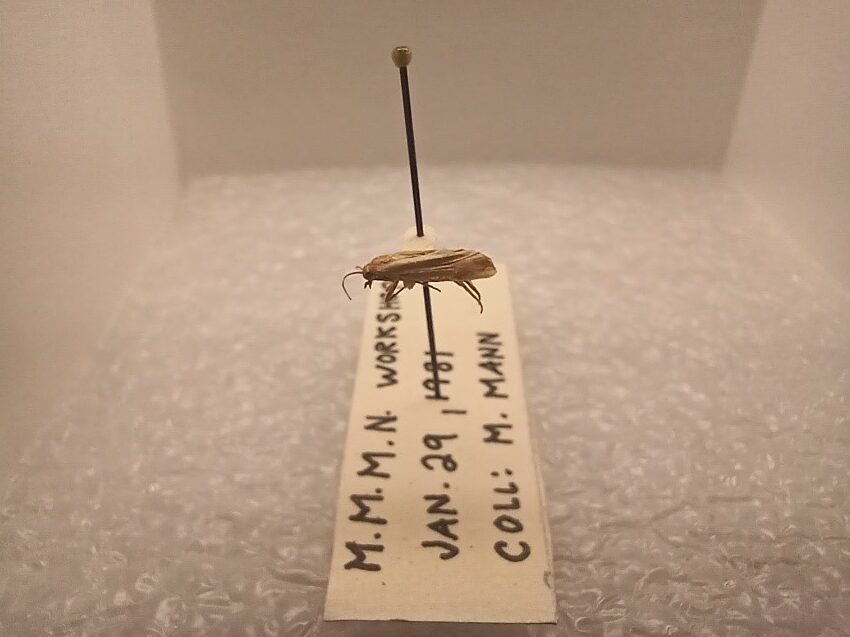

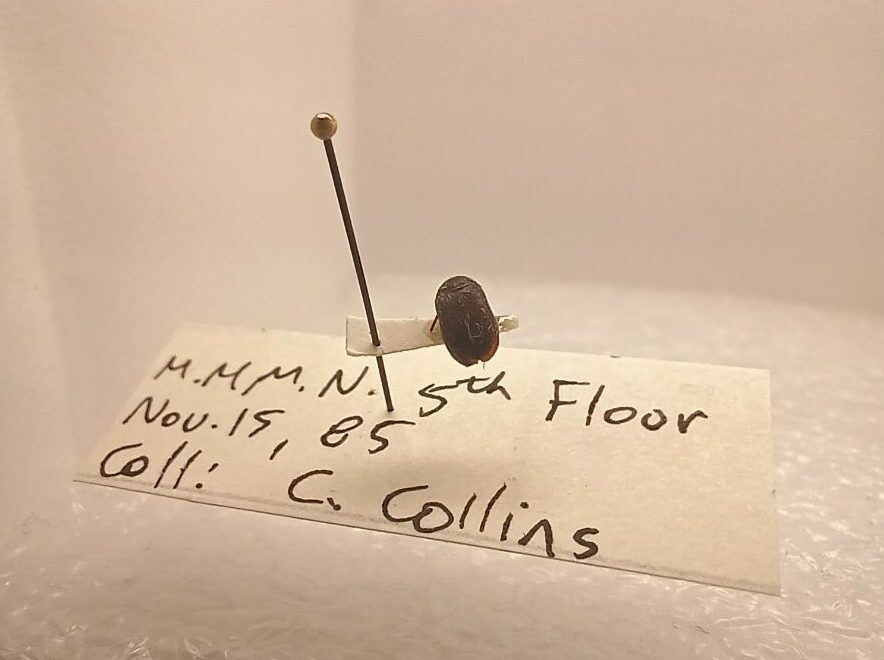

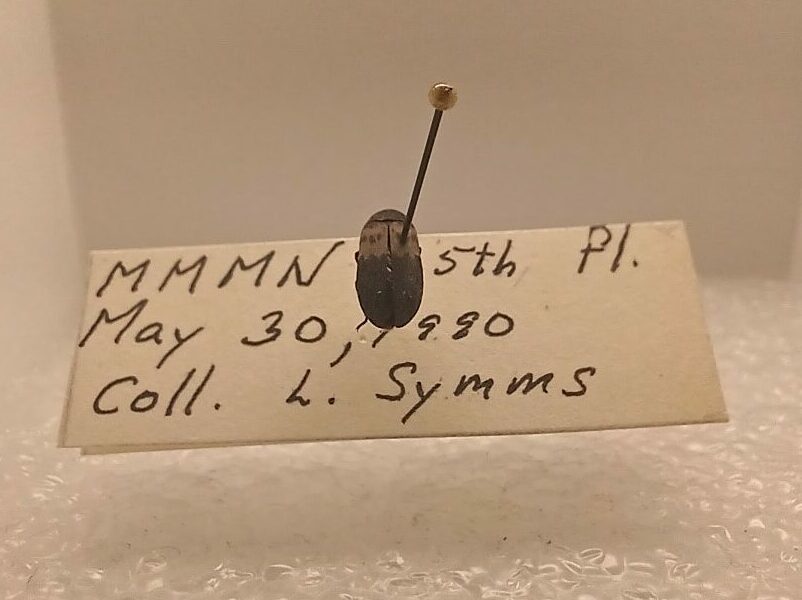

As the label suggested, inside I found a collection of insects that are known to be destructive to museum collections. Capable of eating textiles, paper products, dried plants, and furs, these little insects can be a huge problem if allowed to reproduce in the museum. The specimens were old, their data labels yellowed with age, collected between the ‘70s and the ‘90s by watchful staff right here in the Manitoba Museum.

On an ecological note, it is important to bear in mind that there is nothing inherently “bad” about the organisms we have labeled here as pests. In nature, these insects act as nutrient recyclers and food for many other animals. It is only when their behaviour impacts the livelihood and resources of humans that an animal becomes a “pest”. In this situation, we are simply at odds – our job is to acquire and protect a vast collection of objects with historical and scientific value (or, as the pests would call it, “a huge pile of food with nutritional value”), and their job is to eat well and survive long enough to reproduce.

All that being said, it is my pleasure to introduce you to the insatiable insects of the Manitoba Museum’s Rogues’ Gallery.

Clothes Moth – Tineola bisselliella

The clothes moth is a small, drab moth that packs a punch. In nature, these moths lay their eggs in the nests and carcasses of mammals and birds, providing their caterpillars with easy access to a feast of fur, flesh, and dead insects. In their capacity as pests, they enter buildings and lay their eggs in the presence of animal-derived textiles, specifically those made of wool, silk, and leather. This behaviour ensures that their young have plenty to eat. Walking through the galleries, you may be able to picture the damage that they could do to the historical garments, animal furs, and insect specimens that are on display for the public along, with our stored collections.

Interestingly, the adults of this species do not eat at all, so all of the energy they need to disperse and reproduce comes from food eaten by the caterpillar. The adults of the clothes moth tend to crawl rather than fly. This slow and low movement, combined with their understated colour palette and small size, makes them exceptionally sneaky They can avoid detection by humans with ease, making vigilance and pest control measures a must.

Black Carpet Beetle – Attagenus unicolor

These beetles are tiny – so small, in fact, that the specimens here are pointed rather than pinned directly. As with the clothes moth, the adults disperse to lay eggs near food sources and the larvae that emerge from the eggs do most of the damage. The tiny larvae of these beetles mostly eat natural fibres like wool and silk, making them a threat to clothing, carpets, and rugs stored and on display in the museum. They additionally can eat feathers, fur, and other animal bits, so it is essential that they be kept away from natural history specimens in the galleries and collections. Larvae of these beetles are able to slow their growth when food resources are scarce. Development to the adult life stage can take anywhere from three months to three years! This makes them very difficult to eradicate completely, and even if an infestation appears to be over resurgence is always a possibility.

The Larder Beetle – Dermestes lardarius

The larder beetle (a member of the Dermestid beetle family) may be a familiar insect to some Manitobans. They occasionally wander into kitchens and pantries in search of food, have a distinctive band of yellow hairs crossing their otherwise black bodies, and are generally large enough to be spotted when they move. While they tend to crawl in small, dark spaces, they can also disperse across larger distances by flying. As with the clothes moth, larder beetles are nutrient recyclers in nature, eating plants and animals in various states of decay and returning their nutrients to the soil. If they get into your home, they survive on stored foods such as grains and dried meats, and under the right circumstances major infestations can develop. In a museum, these beetles are able to cause downright havoc

They eat wool, leather, silk, dried plant materials including seeds and grains, animal furs and skins, preserved insects, and even paper. The larvae of this species are particularly hazardous to our collections, as their small size combined with their capacity to climb walls allows them to get to any food that they detect. As if all that wasn’t enough, the larvae are able to bore through solid materials such as wood and plastic. In some cases, they have even been known to bore into tin cans to get at the preserved foods inside!

Pest Control Measures

Due to the damage that they can cause, keeping pests away from the collections of The Manitoba Museum is a matter of utmost importance as we strive to protect the scientific and historical value of the all that is within our care. However, we cannot simply decide that insects will stay out of our museum, as they can fly in through a window, walk through the front door, or even hitch a ride on the clothing of unsuspecting guests. Once they are inside the museum, our pest control measures are the first line of defense.

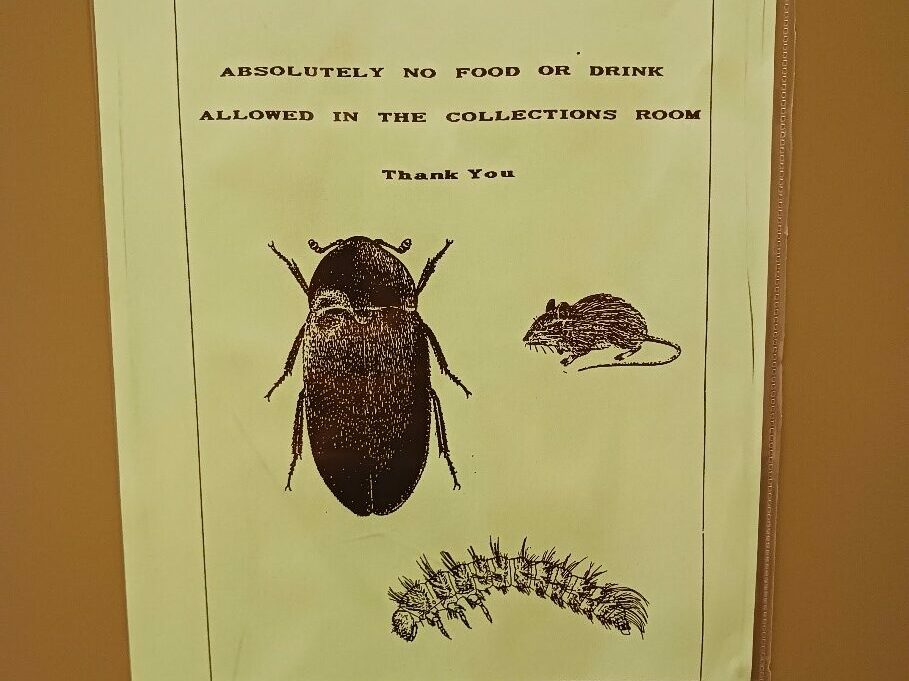

As a basic measure, food items cannot be brought into certain areas of the museum. In the galleries, many displayed objects and specimens are behind glass cases to physically prevent insect access. Baited sticky traps in use throughout the museum are an excellent way to catch insects when they are present, and monitoring them closely allows us to detect problems before they get out of hand. When new items are acquired by the museum, they are frozen twice or exposed to carbon dioxide to get rid of any insects that may be hitching a ride, even as eggs or larvae. Items held in our collections storage rooms are kept in sealed metal cabinets that can keep out even the smallest of insects. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, protection from pests relies on the vigilance of our team. Museum staff monitor items on display and in the collections for signs of insect activity such as feeding damage, shed skins, frass (for the uninitiated, that’s a technical term for sawdust from bore-holes and insect poop), as well as live insects.

Productive Pest

With all that being said, you might think that we strive to keep our museum completely insect free; however, this is not quite true. Hidden away deep in the museum and behind three locked doors there lies a small, sealed room that a lovely brood of six-legged museum volunteers call home. While cleaning the bones of smaller natural history specimens is a painstaking and time-consuming task for a human, our family of Dermestid beetles is always ready for a meal. Paid only in food, the beetles get our bones thoroughly cleaned and ready for final preparation. Next time you visit the museum, be sure to remember the roles that pests play as friends and foes in the museum as we strive to keep our collections in excellent condition for the research and enjoyment of generations to come. And please, don’t bring any food or drinks into the galleries; protection of the collections also depends on you!

Further Reading:

For more in-depth information on our bone-cleaning Dermestid beetles, check out Janis Klapecki’s blog post, Ladies and Gentlemen…The Beetles

Other resources:

https://extension.umd.edu/resource/clothes-moths

https://museumpests.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Larder-Beetle.pdf

https://extension.psu.edu/larder-beetle

https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/fabric/black_carpet_beetle.htm

Aro van Dyck

Collections Technician – Natural History

Menelik Lodge No. 528

To celebrate Black History Month, Curator of History Roland Sawatzky joins forces with Naomi Dennie, a teacher in Seven Oaks School Division and creator of Amplify Us, a podcast series to amplify Black experiences in the Canadian educational system. They share the story you might not know about Winnipeg’s “Elks”.

Image above: Official greeting from Ernest C. Brown, the Exalted Ruler of Menelik Lodge No. 528, in the Souvenir Program of the 10th Anniversary of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, 1952 (which replaced the Order of Sleeping Car Porters, established in 1917). Mr. Brown was himself a porter for the Canadian National Railway. H9-37-195, Manitoba Museum

Menelik Lodge No. 528 was founded by Winnipeg railway porters in 1917 to support the Black community with fundraising, education, and social activities. The Lodge was part of the North American fraternal society known as The Improved, Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks of the World (IBPOEW). The IBPOEW was founded in Cincinnati in 1898 by Arthur James Riggs and Benjamin Franklin Howard, who wanted to form an alternative to the all-white Order of the Elks.

They began the society for “the expression of ideals, services and leadership in the black struggle for freedom and opportunity.” Lodge No. 528 also ensured financial support for members who became ill, and death benefits for relatives of deceased members. According to Sarah-Jane Mathieu, author of North of the Color Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, porters also “likely used lodge meetings as covers for their union plotting.”

The “Elks,” as they were known, held regular meetings at 795 Main St., a building that still stands today beside the Sutherland Hotel. The Lodge had popular regalia, including purple fezzes and ribbons, and the usual oaths confirming mutual support. The Menelik Lodge held large annual picnics in August, as well as dances and banquets. Additionally, there was a Ladies Auxiliary and a “Junior Elks Herd” for kids.

The Elks were profoundly impactful to Winnipeg history and should be honoured for their commitment to the Black community and their involvement in political and social activism throughout their duration.

Fun Fact!

Menelik Lodge adopted its name from Emperor Menelik of Ethiopia, who was said to be the son of the Biblical figures Queen of Sheba and King Solomon. Emperor Menelik II (1844-1913) may also have been an inspiration, as he helped create the independent modern state of Ethiopia.

Join us in Museum Galleries Saturday afternoons in February to see these artifacts on display as part of our Black History Month pop-up mini-exhibit.

Bundle and save! Save 25% when you purchase tickets for all three attractions.

Dr. Roland Sawatzky

Curator of History

Did you know that Manitoba has no Red Wildflowers?

#DYK Manitoba has no truly red wildflowers? Find out why in this video with Dr. Diana Bizecki Robson, our Curator of Botany.

Did you know? Ram’s head snuff mull

Did you know that this bejeweled ram’s head in the HBC Gallery has wheels on the bottom? It’s a snuff mull from the 1800s.

Learn more about this peculiar artifact with Erin from our Learning and Engagement team!

In Manitoba, the Roses Aren’t Red

It’s almost Valentines Day and the flower that most people associate with that holiday is bright red. Long-stemmed red roses have long been the flower of choice for people wooing their sweethearts. But if you’ve ever gone hiking in a wild Manitoba grassland or forest, you might have noticed that the roses we have here are pink, rarely white, but not red. In fact, there are no bright red wildflowers in our province. Why not?

Why Flowers Have Colour

To understand the lack of red flowers in Manitoba, we need to think about why flowers exist at all. Flowers are the reproductive organs of plants; they produce eggs and/or pollen. Since plants can’t move around to find a mate, they often use animals to move the pollen from one flower to another. Successfully transferred pollen fertilizes the eggs of the receiving flower. To attract animals, plants grow structures that animals will find attractive, like beautiful or unique scents, and petals with eye-catching colours. They also usually reward the pollinator with nectar.

Scarlet Paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea) is one of the reddest wildflowers we have in Manitoba, but it tends to be orangey-red rather than bright red. © Manitoba Museum

Wild Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) attracts hummingbirds, but butterflies, moths and bees are also important pollinators of this plant. © Manitoba Museum

The Nature of Colour

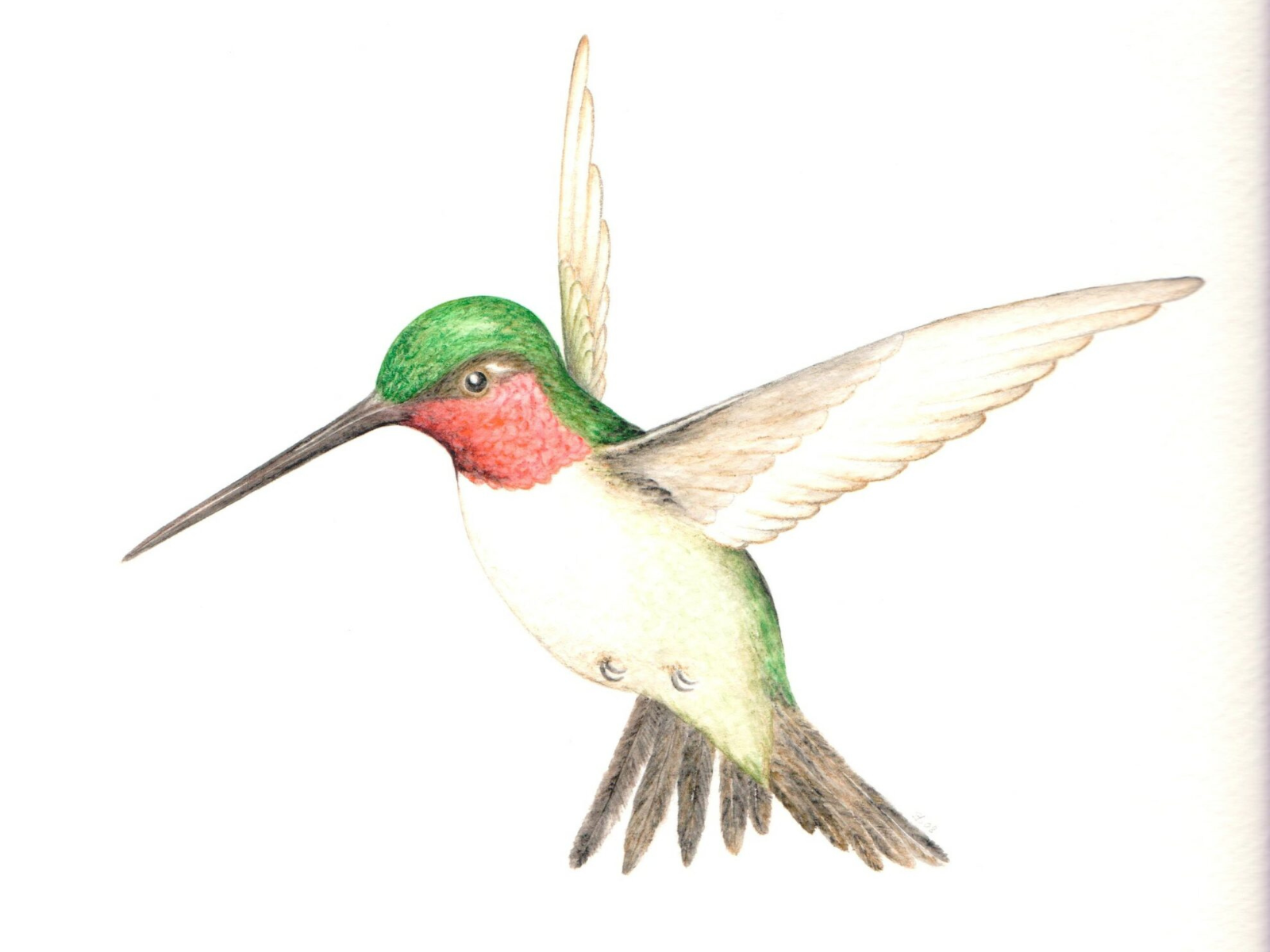

Colour exists because different surfaces reflect different wavelengths of light. Light is made up of a whole spectrum of colours, evident in a rainbow or when light shines through a prism. Just like some animals have a better sense of smell than others, they also see things differently. Birds and humans can see red flowers quite well, but most insects cannot. To an insect, red is difficult (though not impossible) to tell apart from green leaves. For this reason, areas where birds are common pollinators (such as tropical rainforests) tend to have lots of red flowers. Areas with mostly insect pollinators typically have lots of yellow and violet flowers. In Manitoba, our only bird pollinators are hummingbirds, the most common being the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris).

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) move pollen from flower to flower in exchange for a nectar reward. Illustrated by Silvia Bataligni © Manitoba Museum

Abundant Insect Pollinators

Insects are the most abundant pollinators in Manitoba, so most of our flowers are highly attractive to bees, butterflies, moths, flies, wasps and/or beetles. Flowers that are orange, yellow, blue and violet are most attractive to insects, as these colours are readily visible to them. However, unlike humans, insects can also see into the ultraviolet (UV) range. This ability explains the presence of so many, seemingly white flowers in the province. Flowers that we see as pure white or plain yellow, actually usually reflect UV rays, and look much different to insects than to us. White flowers are also often pollinated by moths, because white is more visible in moonlight than any other colour.

Small bees and flies, not birds, pollinate our wild roses, including Prairie Rose (Rosa arkansana). © Manitoba Museum

Many insect-pollinated plants, like Dandelions (Taraxacum sp.) have patterns that are visible only under UV light (left) © Wikimedia Commons CCA-SA 4.0

Why do cultivated roses look different from wild roses?

Humans have been cultivating roses for thousands of years. In the process, we selected features that we find attractive but that make them largely unattractive to pollinators. Colour is one factor. Insect pollinators do not usually visit red roses because they can’t see them very well. Further, cultivated roses have many, densely packed petals (not just five like the wild ones), that cover up the pollen-containing anthers, making them difficult for pollinators to access. So, the end result is that these beautiful flowers now function only as aids to human, not wild, romance.

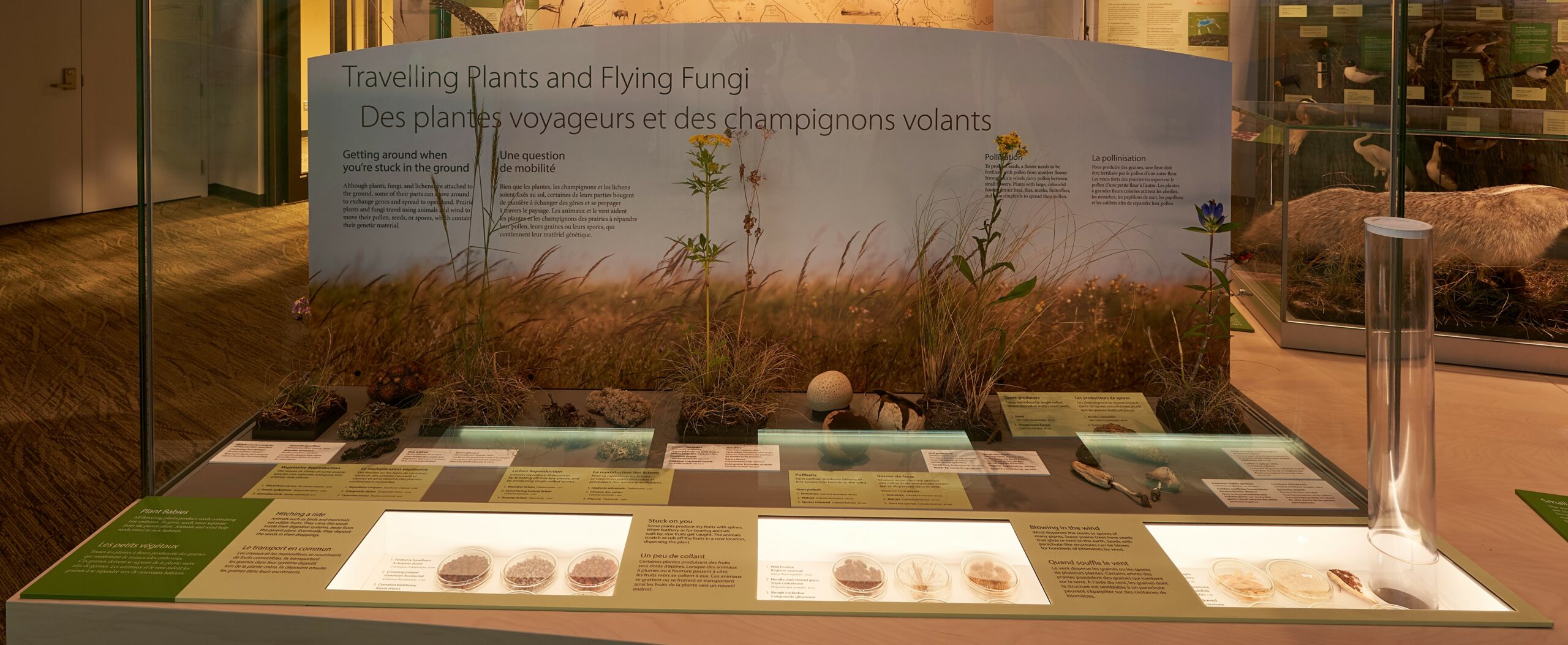

The Manitoba Museum’s new Prairies Gallery has a whole exhibit on pollination where you can see what native pollinators look like. © Ian McCausland/Manitoba Museum

Dr. Diana Bizecki Robson

Curator of Botany

Science in the Snow

By Mike Jensen, Planetarium/Science Gallery Programs Supervisor

When thinking of activities to do on a bright Winter’s day, science doesn’t usually come to mind. Surprisingly, science is at work with almost every fun pastime you can conduct out in the snow. You just need to know what to look for!

Of course, the first thing you think about as you zoom down a snow-covered hill on your favorite toboggan is physics, right? Well, it should be, because the laws of physics are actually in the driver’s seat when you are careening down a slope with no brakes. Next time you hit the slopes, conduct some experiments.

- Do you go faster with more or less weight?

- Does the shape or type of material of your toboggan affect how fast you go?

- Does a steeper or gentler slope make a difference to your speed?

Once you are done experimenting with your sled, shore up your engineering skills by building a snowman. Surprisingly, it’s not as simple as you think. Here are some science and engineering factors to consider when making Frosty in your front yard.

- Moisture content. Snow can be too wet or too dry, so having the right amount of water to ice crystals can make or break your construction. Water is the glue that sticks the ice crystals together.

- Pack it down. This actually melts some of the snow, which then re-freezes and helps to bind the snow together.

- Watch your center of mass. There’s a reason the largest snowballs go on the bottom. Don’t go making Frosty top-heavy, otherwise you risk catastrophic failure.

After you’ve had your fill, come put your new-found science and engineering skills to the test at the Manitoba Museum’s Science Gallery. Design and build your newest creation at the LEGO brickyard, or see if you can be the first to cross the finish line at the Engineered for Speed Race Track!

The Blanket That Crossed the Atlantic During WWII

Did you know that this quilt crossed the Atlantic during war-time only to find its way home over 70 years later?

When the weather turns cold, many of us reach for the warmth and comfort of a handcrafted quilt or afghan. During WWII, local volunteers gathered in Steep Rock, MB to create Red Cross quilts for civilian victims of the war. Across the Atlantic, at Dudley Road Hospital in Birmingham, England, a Matron passed their gift on to Cynthia (Betty) Craddock. Her husband Joe was serving in the army when their only son Anthony was born in 1945.

Anthony’s earliest memories are “of this quilt being on my bed and keeping me warm when times were hard. With no central heating, frost would often appear on the inside of the window.” The young Anthony remembers reading the message on a tag on one corner of the quilt. Betty treasured the gift for many years until finally they decided that it was time for the quilt to be sent home.

You can see the quilt along with photos of Betty and Anthony Craddock in our Parklands Gallery.