But many visitors don’t realize that most of the museum’s collections are not on exhibit. For example, over 95% of our bird collections, almost 7,000 specimens, are in climate-controlled storage on the 4th floor.

Why would we have all these bird specimens if they aren’t on exhibit? Where did they come from and why so many?

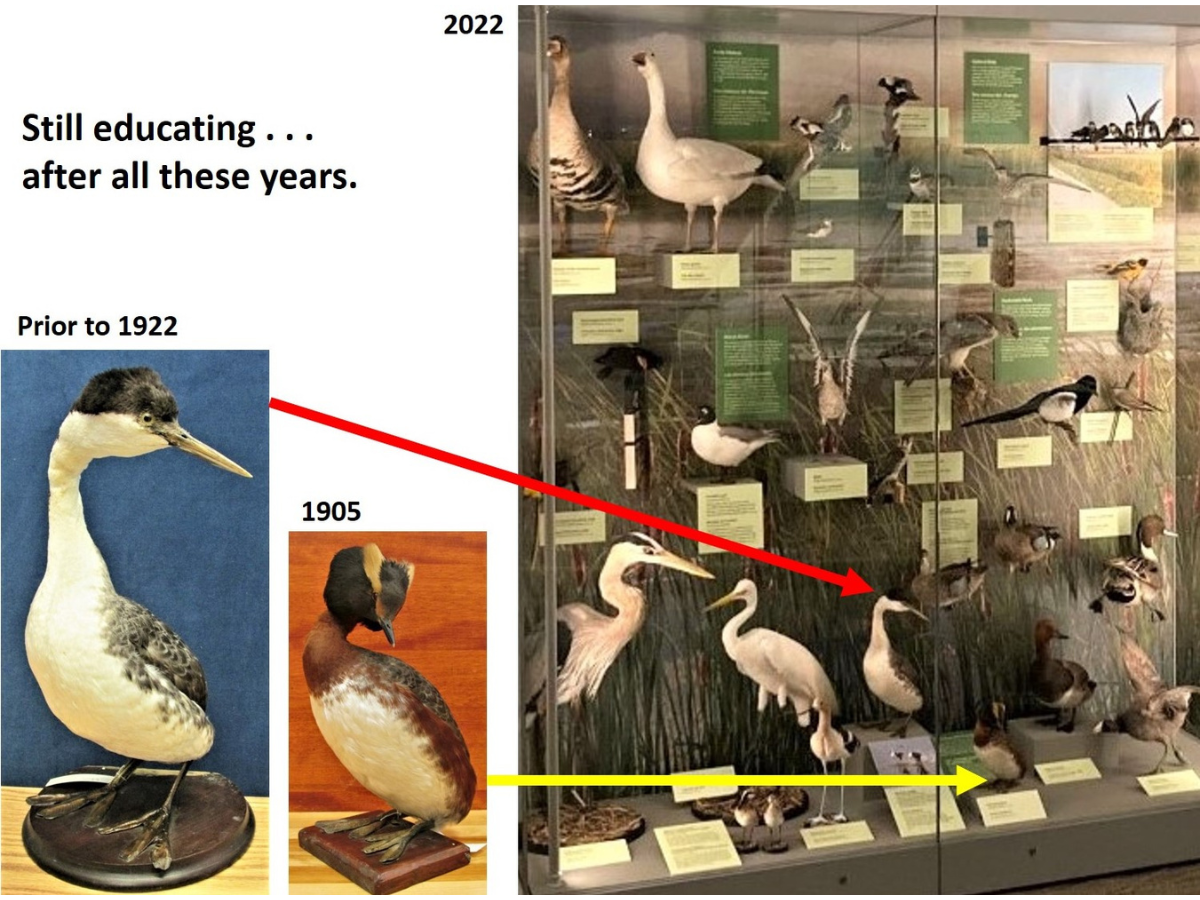

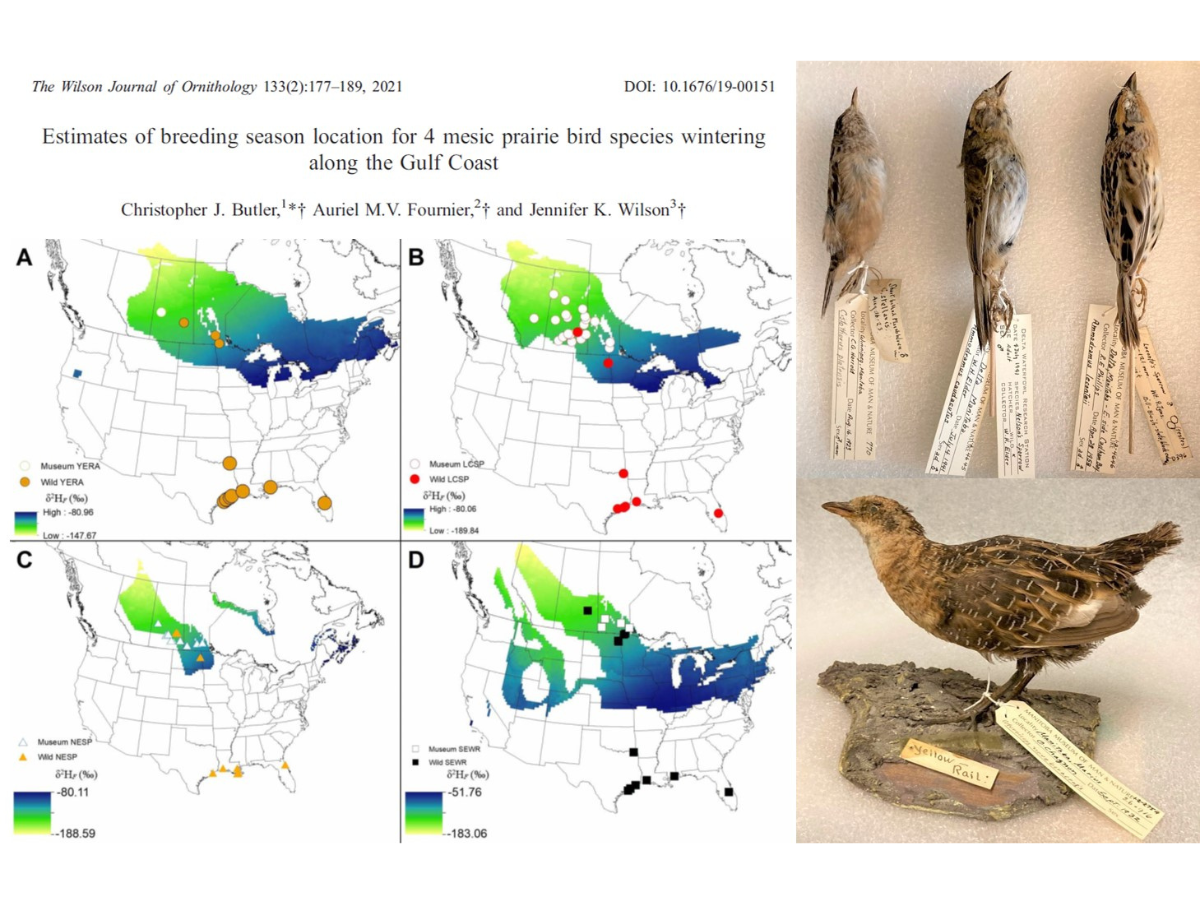

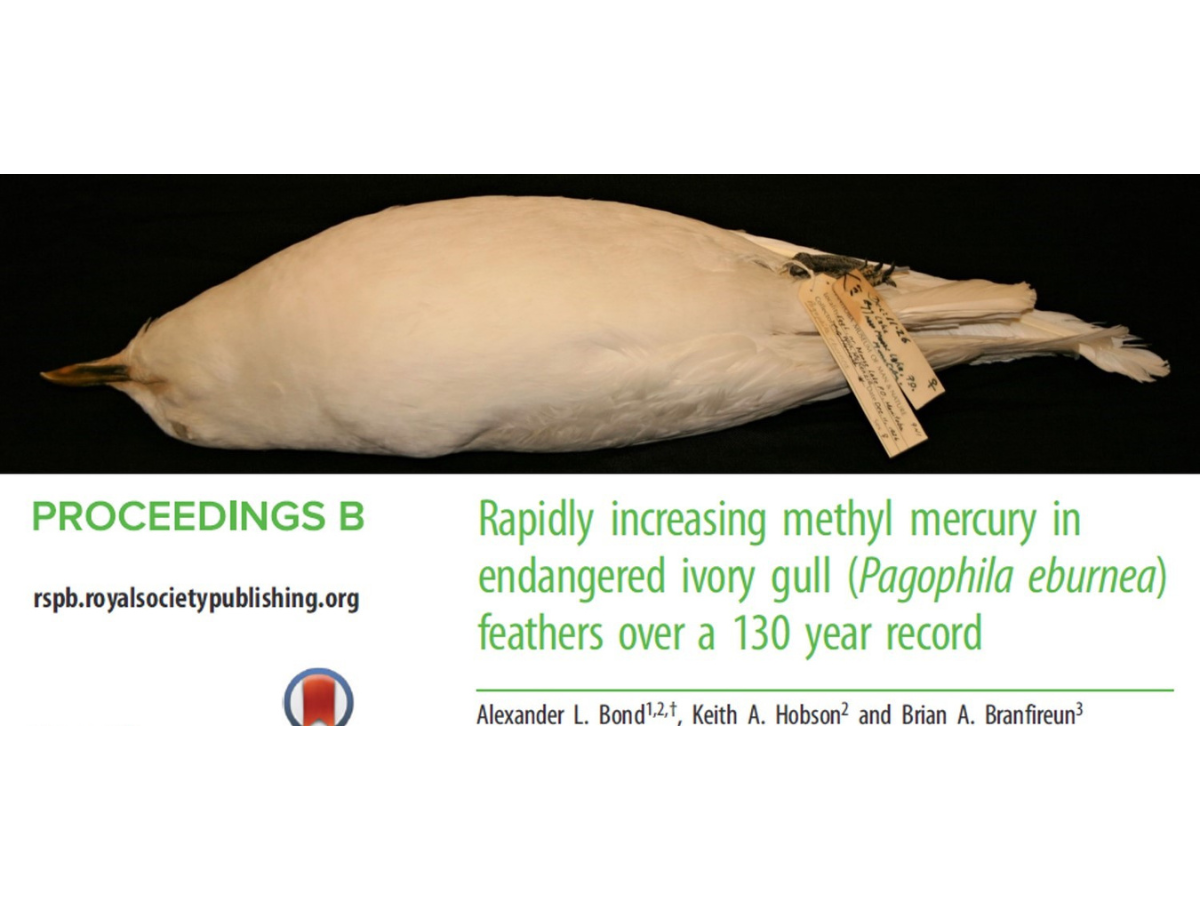

Our behind-the-scenes bird collection is a combination of inheritance from earlier versions of the Manitoba Museum, donated private collections, and, more recently, window and vehicle casualties brought in by the public or through relationships with zoos, government, and universities. In the distant past, birds could be professionally collected and were even traded among private citizens. That practice is, thankfully, no longer allowed, but many of these collections, some more than 100 years old, were eventually donated to the Museum where they have had a second ‘life’ through their value for public education and for scientific study. These specimens not only grace our exhibit halls, but have contributed information that appears in our exhibits as labels, short panels, or videos through primary research by scientists at the Manitoba Museum and researchers from around the world.

Having large numbers of bird specimens means that we can learn a great deal about where they live, what they eat, and other aspects of their life histories. Like people, each individual bird is unique, but having several from different places provides a statistical sample and a better understanding of their biology and a record of geographical variation in size, colour, and behaviour.

The collection is like a library or archive of the lives of birds in Manitoba. And like a library, scientists can read and borrow the ‘books’, the specimens, to study them and to discover the stories they tell about how our birds live and what they tell about our environment in general.