During this cold March, the new Prairies Gallery is a comfortable place to explore the diversity, adaptations, and life histories of some of Manitoba’s wildlife. For many visitors, especially the young, the exhibits often provide the first close look at the details of insect wings and wolf teeth, the first chance to explore life underground, or to experience the wonder of just how many other animal species are fellow Manitobans.

That can mean that a gallery or exhibit is an important influence on attitudes towards our environment and might inspire the next generation of conservation advocates. And parts of our collections, including some birds now on exhibit in the new gallery, have a long history educating the public and have been filling that role for almost 100 years!

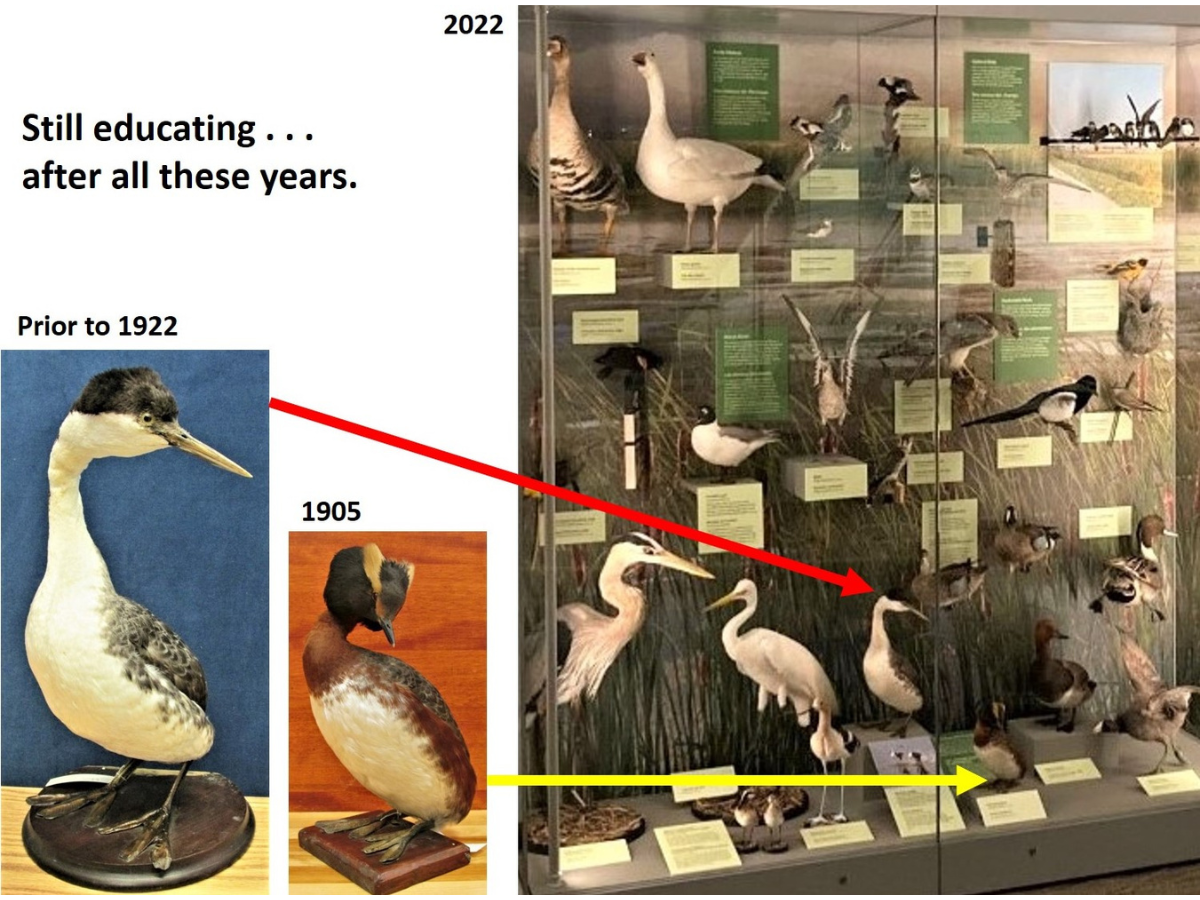

Some specimens in our collections have been teaching about biodiversity for over 100 years, including the western grebe (left) and horned grebe (middle) continuing that role in the new Prairies Gallery (far right). MM 3-6-4, MM 3-6-359

© Manitoba Museum

But many visitors don’t realize that most of the museum’s collections are not on exhibit. For example, over 95% of our bird collections, almost 7,000 specimens, are in climate-controlled storage on the 4th floor.

Why would we have all these bird specimens if they aren’t on exhibit? Where did they come from and why so many?

Our behind-the-scenes bird collection is a combination of inheritance from earlier versions of the Manitoba Museum, donated private collections, and, more recently, window and vehicle casualties brought in by the public or through relationships with zoos, government, and universities. In the distant past, birds could be professionally collected and were even traded among private citizens. That practice is, thankfully, no longer allowed, but many of these collections, some more than 100 years old, were eventually donated to the Museum where they have had a second ‘life’ through their value for public education and for scientific study. These specimens not only grace our exhibit halls, but have contributed information that appears in our exhibits as labels, short panels, or videos through primary research by scientists at the Manitoba Museum and researchers from around the world.

Having large numbers of bird specimens means that we can learn a great deal about where they live, what they eat, and other aspects of their life histories. Like people, each individual bird is unique, but having several from different places provides a statistical sample and a better understanding of their biology and a record of geographical variation in size, colour, and behaviour.

The collection is like a library or archive of the lives of birds in Manitoba. And like a library, scientists can read and borrow the ‘books’, the specimens, to study them and to discover the stories they tell about how our birds live and what they tell about our environment in general.

The Manitoba Museum holds almost 7,000 bird specimens. This library of bird life is not only a resource for exhibit and teaching, but is available to Museum scientists and researchers around the world. © Manitoba Museum

So how can these bird specimens contribute to conservation?

Collections include birds from over many decades that act much like a time machine, letting us know where and in what quality of environment they lived. Specimens provide baseline data for knowing a species occurrence and range at a specific time in the past and whether it is still there. This can help determine if species are being affected by climate change, habitat loss, or other factors. Today, bird records can include photographs and sound recordings, but this technology has only very recently been widely available. Where birds lived 30, 50, or 100 or more years ago can only be determined with certainty by voucher specimens, that is, physical evidence that a species was found at a particular place at a particular time. But even today, because Manitoba is a big province and much of it is difficult to access, we are still unsure of where some species occur. Museum curators are among the few scientists performing on-the-ground surveys to determine baseline data on distribution and retaining physical evidence of that distribution. Without these comparative data we can’t know what might be changing nor determine if conservation action should be undertaken. It is impossible to be responsible stewards of our natural world if we don’t know what lives where!

Most of Manitoba’s birds spend only a few short, warm months here to raise their young and then spend the majority of the year to the south. That means that even if we take appropriate conservation measures to safeguard our birds here, they face further challenges elsewhere. But where is that elsewhere?

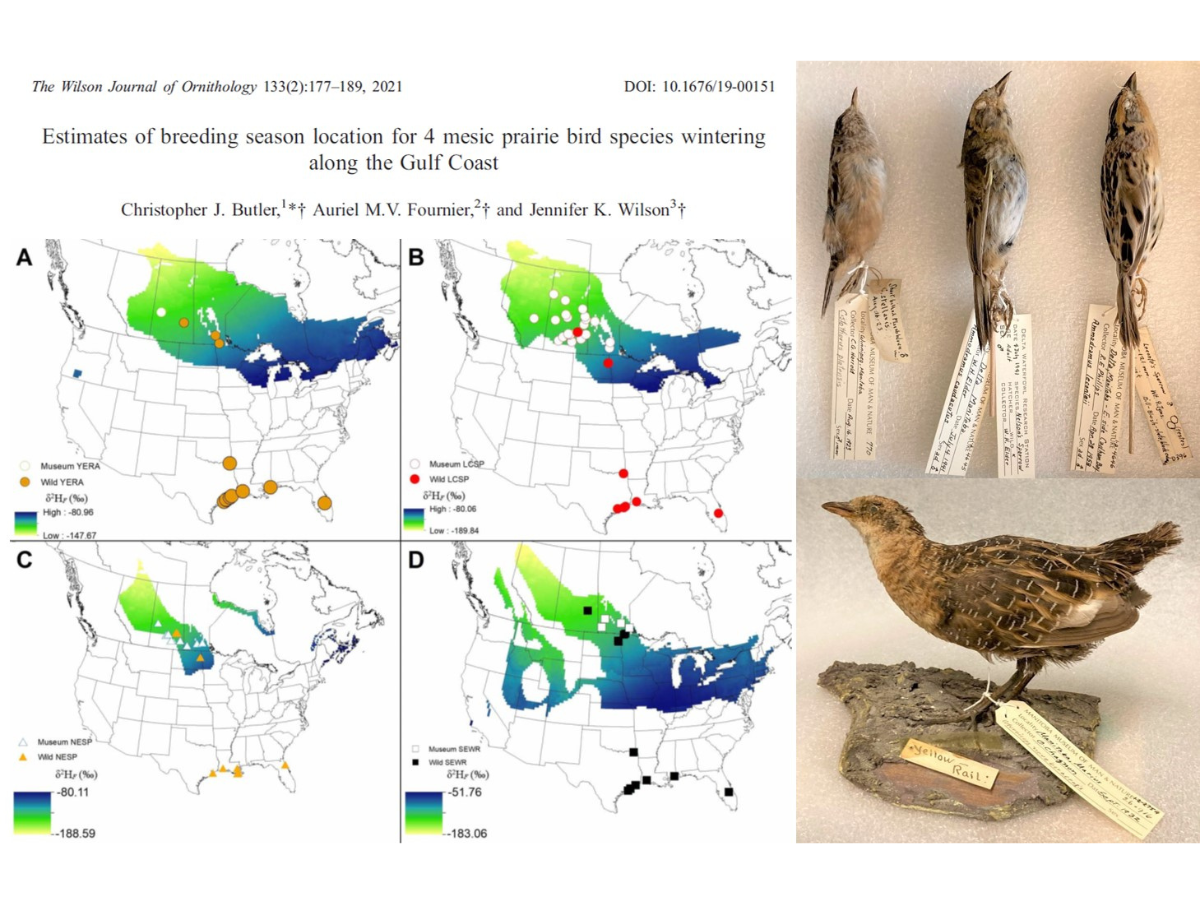

Collections can help to determine where our birds spend the winter and can pinpoint where international collaborative conservation efforts should be directed. A recent study spear-headed by researchers at the University of Central Oklahoma used feather samples from specimens in the Manitoba Museum and other institutions to examine their unique molecular signatures (isotopes) to determine where four species of prairie birds overwinter. They found, for example, that prairie populations of the elusive yellow rail (Coturnicops noveboracensis) – a species of special concern in Canada – spend their winters in the western portions of the Gulf of Mexico. Conservation policies can now be introduced to better manage habitat in both the breeding and wintering ranges for this rarely encountered species.

Feather samples from Manitoba Museum specimens helped to determine that prairie breeders overwinter along the western Gulf of Mexico. From Butler et al., 2021. Estimates of breeding season location for 4 mesic prairie bird species wintering along the Gulf Coast. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 133:177-189. Photos of sedge wren (MM 1-2-770), Nelson’s sparrow (MM 1-2-4645), LeConte’s sparrow (MM 1-2-4646), and yellow rail (MM 3-6-916) © Manitoba Museum

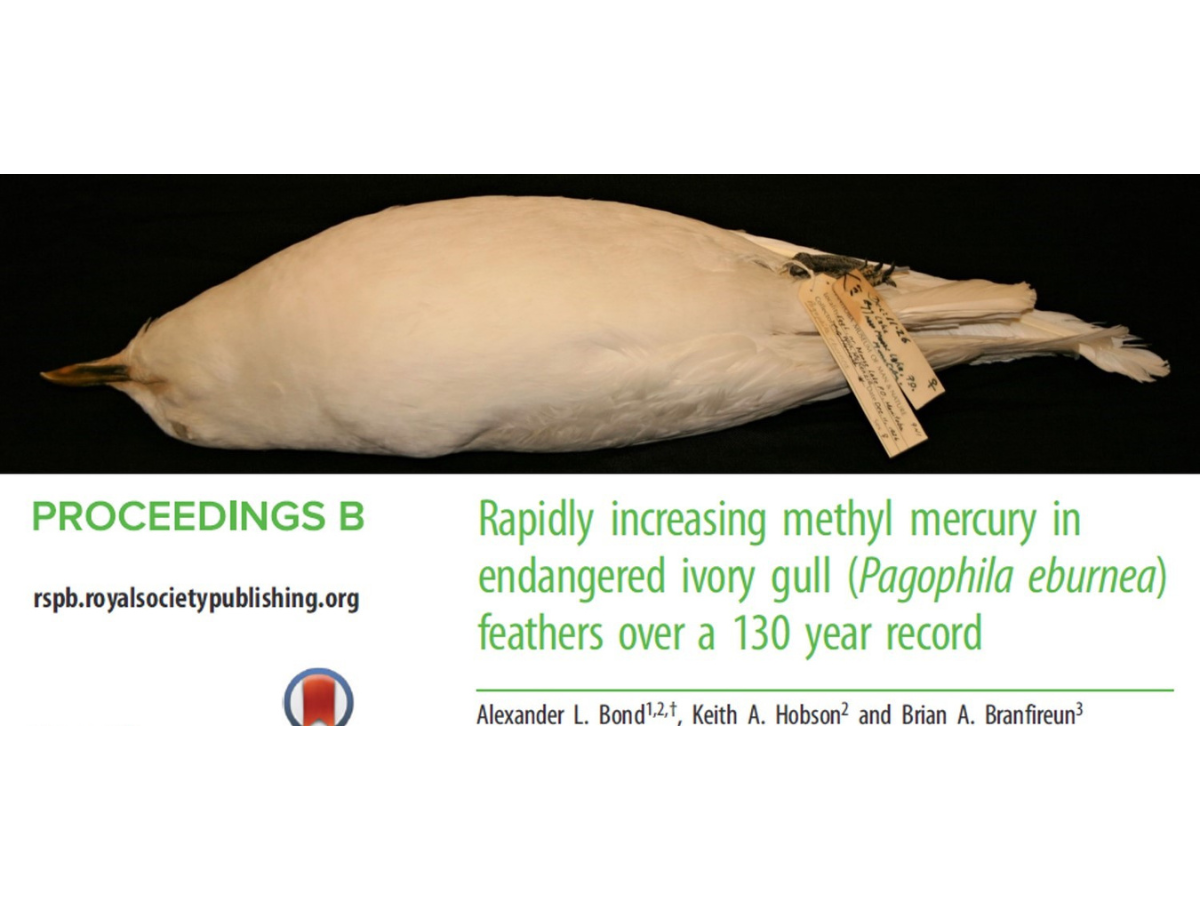

And the collections can provide valuable information about changes in our environment. Using samples of ivory gull (Pagophila eburnean) from several museums, including a 1926 specimen from the Manitoba Museum, university and Environment Canada researchers recreated a 130-year record of mercury levels in this endangered species. This time series, like a time machine, could trace the history of mercury contamination in this Arctic gull, finding that levels have increased dramatically in northern food webs. This museum collection-based study showed that bioaccumulation, the gradual build-up of heavy metals through the food chain, puts top predators like the ivory gull, fishes, and marine mammals at risk from pollutants like mercury.

The 1926 ivory gull from the Manitoba Museum (above) was one of many museum specimens analyzed to create a 130-year history of mercury levels that will inform management plans for this and other Arctic species. From Bond et al., 2015. Rapidly increasing methyl mercury in endangered ivory gull (Pagophila eburnea) feathers over a 130 year period. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282. Photo MM 1-2-941, © Manitoba Museum

Museum collections go well beyond their important educational role in exhibits and programming to create advocates for conservation. As permanent archives of the distribution of organisms and as a critical resource for scientific research at the Museum and at science institutions around the world, specimens in the hand contribute to understanding our environment and determining strategies and policies for responsible ecological stewardship. Although I have focused on bird collections to illustrate a few applications, the Museum collections of insects, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and other animals, along with those of plants, mosses, lichens, and fungi, as well as the representative fossils of these and earlier organisms in the paleontology collections, provide important data to interpret the past, understand the present, and consider the future of the natural world in Manitoba.