Posted on: Tuesday March 10, 2015

When people ask me what inspired me to work in the museum field, I can pinpoint my answer to a single visit to The Manitoba Museum when I was twelve years old. That summer we spent our vacation touring around Manitoba on day trips, packed into our Pontiac 6000 station wagon, visiting small local museums and landmarks that set one little town apart from the next (here’s looking at you, Sara the Camel!). On the roster of things to see was The Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature (as it was called back then). Thanks to my babysitting job, I was armed with a newly purchased camera and ready to capture every moment of our visit. Rounding the corner away from the bison that greeted us in the first gallery, I stopped. There it was, colourful and bold, larger than life. The mural. Snapping a photo, I decided at that moment, I needed to work at a museum. I still can’t say for certain what it was about that mural that led me to this epiphany, but twenty years later, here I am, working at the museum, blogging about it.

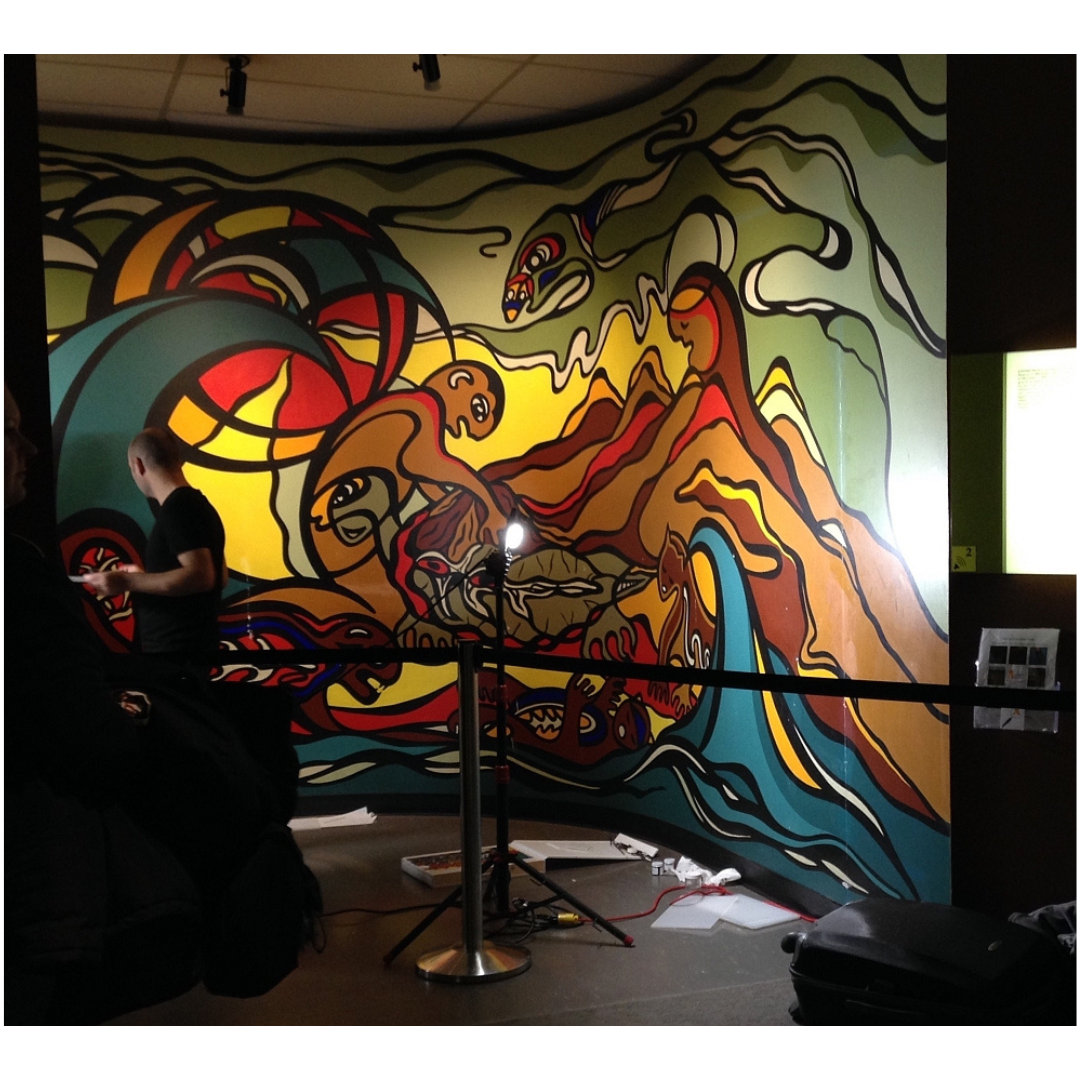

Daphne Odjig, a Potawatomi artist from Ontario, was commissioned to paint the mural, “The Creation of the World”, in 1972 as part of the Earth History gallery. Odjig was living in Manitoba at the time and later went on to cofound the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporated with artists such as Jackson Beardy, whose works also appear at The Manitoba Museum. As I studied Odjig’s larger oeuvre in university, I came to appreciate the uniqueness of “The Creation of the World”, both in its subject matter and execution. Odjig’s paintings often depict human relationships, focusing on mothering, with images composed of darker, more muted colours bordered by softer lines while still harkening to the Woodlands School style “Creation” celebrates.

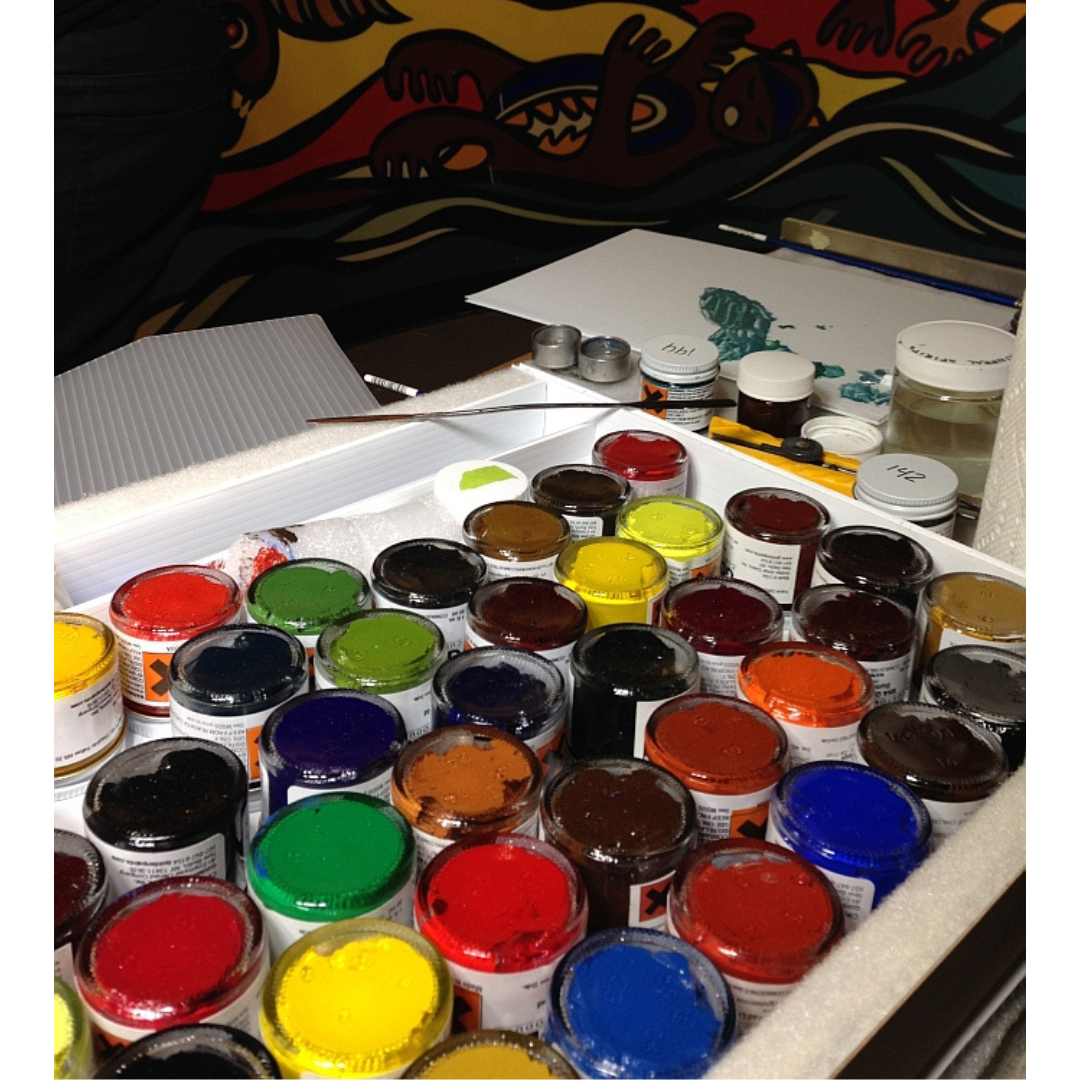

Forty-two years on display had begun to show on the face “The Creation of the World”…pencil marks, gouges from countless strollers crashing into the curved wall, cracks from the shifting plywood have marred the surface of Odjig’s beautiful contribution to the museum. On Valentine’s Day, art conservator Radovan Radulovic and his assistant Vitaliy Yatsewych began a three day restoration of the mural, a process of cleaning, filling in holes, and painting. Radulovic describes the work as trial and error; creating a colour by mixing acrylic paints, painting a spot, letting it dry, deciding if the colour matches the original and starting again, if necessary. The aforementioned cracks, however, are impossible to repair without going in behind the mural or removing it altogether. For the time being, Radulovic and Yatsewych, by all accounts, have brought “Creation” back to its former glory. The addition of a rail guard will prevent errant strollers and carts from damaging the mural and new exhibit panels will put further emphasis on this cherished piece.

Work begins on the mural.

Conservator Radovan Radulovic works on large crack in mural.

A paintings conservator’s tool kit.

Vitaliy Yatsewych mixes colours to create the perfect match.

Yatsewych tests out the colour he created on the mural.

The finished product.

Have a good look at “The Creation of the World” the next time you visit The Manitoba Museum. Marvel at its scale. Absorb the colours. Take a photo. Appreciate its creator and those who continue to preserve it for future museum-goers (so, don’t touch it, ok?).