Posted on: Wednesday April 8, 2020

With changes happening throughout the museum, we sometimes find opportunities to update existing exhibits and breathe new life into old favourites. Last spring, when our temporary exhibition about the Winnipeg General Strike, Strike 1919: Divided City, was installed in our Urban Gallery and the entire gallery received beautiful, new mannequins, I jumped at the chance to revamp one of my favourite exhibits – Madam Taro’s room.

Depending on who you talk to, Madam Taro is a mysterious fortune teller from the old country or a woman earning her living working in the oldest profession. I’m inclined to believe the latter, but I appreciate her ingenuity in maintaining a ruse for decency’s sake. In a nod to her name, we swapped out her “crystal ball” (a glass orb) for a set of tarot cards we have in our collection, a reprint of a tarot deck from 1910, so they fit our time period perfectly. We laid the cards out as if she’s giving a reading, with her ashtray and cigarette holder at hand. We also added a decanter and glasses, in case any of her gentleman callers fancy a drink.

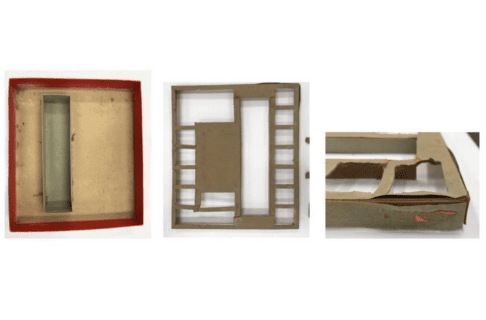

Madam Taro is ready to read your tarot card. Image: © Manitoba Museum, H9-30-731

From there, I decided which pieces should be removed from the room; some based on aesthetics (or the vibe, for my younger readers), others because they weren’t in keeping with the time period. We kept the majority of the furniture and bedding in the exhibit, but put most of the “dressings” like pictures, doilies, garments, and knickknacks back into storage. In their place, I wanted to feature objects that one might find in a woman’s bedroom – make up, nail polish, brushes, hairpins, perfumes, and powders. Thankfully, our collection is chockful of beautiful examples of personal care items from the early 20th century, so I had a lot of selection. The existing wardrobe is staged with the door ajar to give visitors a peek at some clothing, shoes, and accessories from our collection.

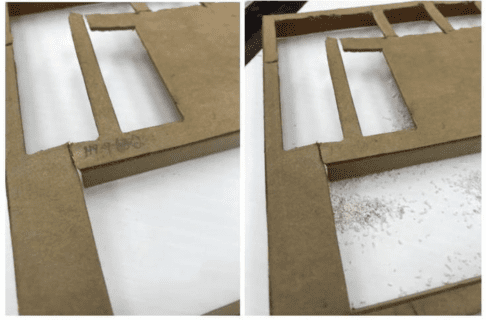

Madam Taro’s dressing table adorned with her personal items. Image: © Manitoba Museum

Close-up of Madam Taro’s personal items. Image: © Manitoba Museum

The main decorative addition to the space is the group of hand fans our talented conservator mounted and hung on the wall as art. This feature complements an existing parasol, feather boa, and astrological chart already decorating the room. We also added a gramophone to the space, along with a few records – and even though you can’t read the labels from the door, I made sure to pick records of the period: for instance, foxtrots by Coleman’s Orchestra, “I’m Coming Back to Dixie and You” by the Peerless Quartet, and “In the Hills of Old Kentucky” by Campbell and Burr.

The less romantic but essential elements of the space include a pitcher and basin for Madam Taro to use for washing up or bathing, and finally, the all-important chamber pot tucked under her nightstand. Her room may have included shared washroom and toilet facilities if any at all, so the chamber pot would come in handy for middle of the night relief.

The most striking change in this exhibit is the new Madam Taro; instead of faceless forms, our new mannequins are lifelike, lending to the story of each exhibit. In this case, we wanted a mannequin who was culturally ambiguous and slightly older, someone who has worked long enough to establish herself and afford the “luxuries” I wanted to showcase in her room. Selecting a head made me feel like I was Princess Mombi in the movie Return to Oz, to be honest! The face we chose has a sympathetic expression with eyes that I feel have a bit of sadness behind them – or like she’s tired after a long day at…the office.

All of these elements – the artifacts, the new mannequin, the staging – work together to create a narrative of a woman working and living in Winnipeg in the 1920s. Next time you’re visiting the Manitoba Museum, make sure you stop by Madam Taro’s for a reading…and maybe more!