Posted on: Wednesday May 23, 2012

For the last several months I have been helping to organize the 23rd North American Prairie Conference (NAPC) (click here for conference details) which will be held at the University of Manitoba from August 6-10. This is first time that this conference has been held in western Canada (it is usually held in the mid to western U.S.). I’m looking forward to learning more about prairie conservation and restoration initiatives from other Canadians as well as our American neighbours. This conference will feature a number of prominent prairie enthusiasts including Canadian authors Sharon Butala and Candace Savage as well as Dr. Wes Jackson from the Land Institute in Kansas and Dr. David Young from the Natural Resources Institute in Winnipeg. Ojibway elder David Daniels will be talking about Canada’s native plants and their traditional use.

The conference banquet will be at the Manitoba Museum.

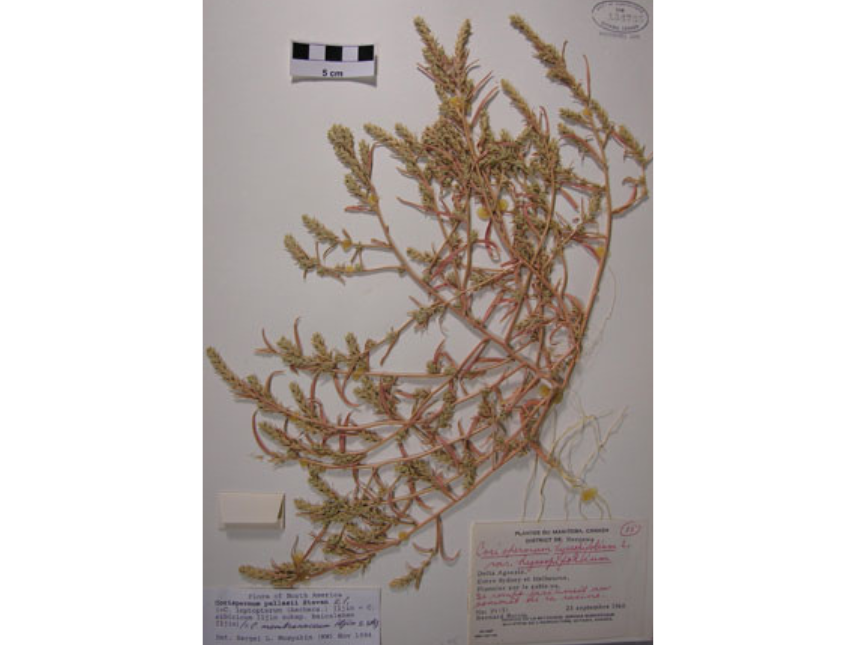

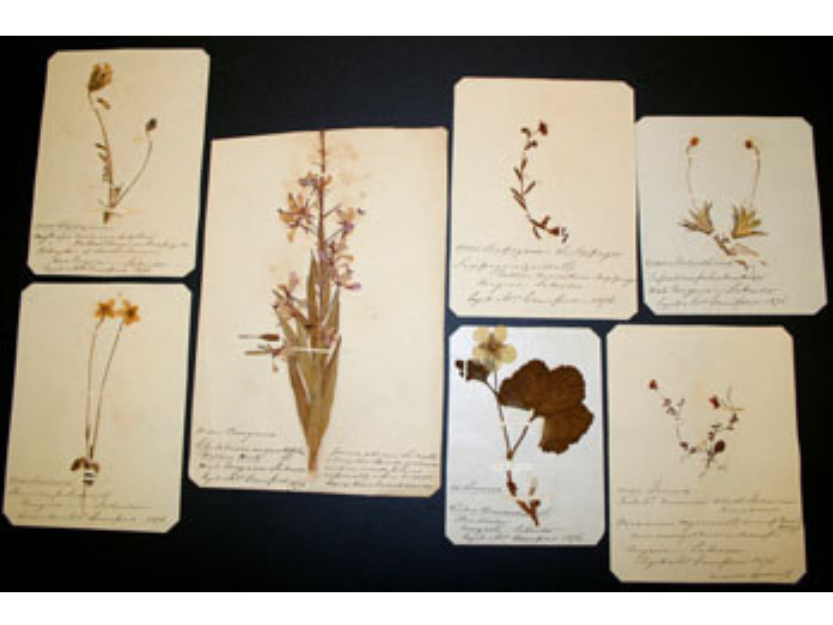

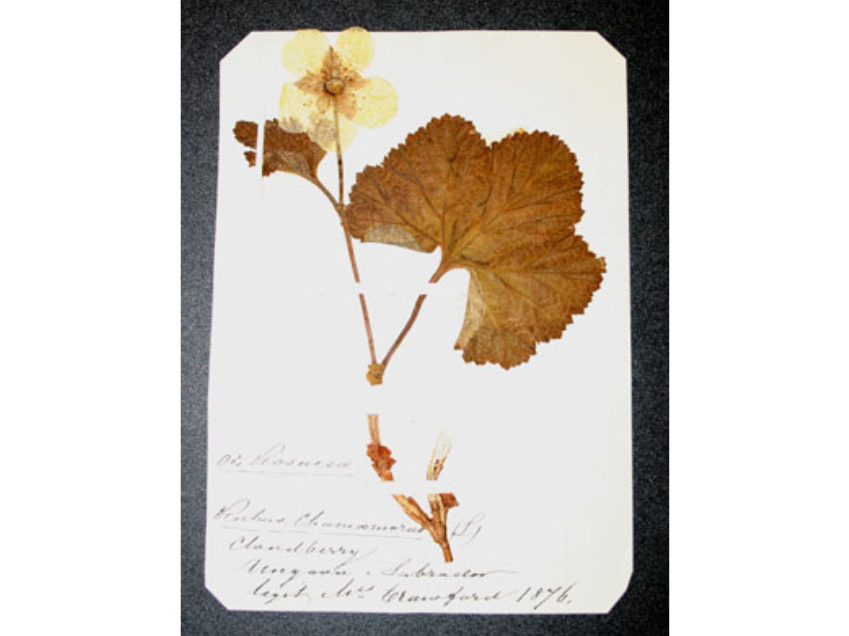

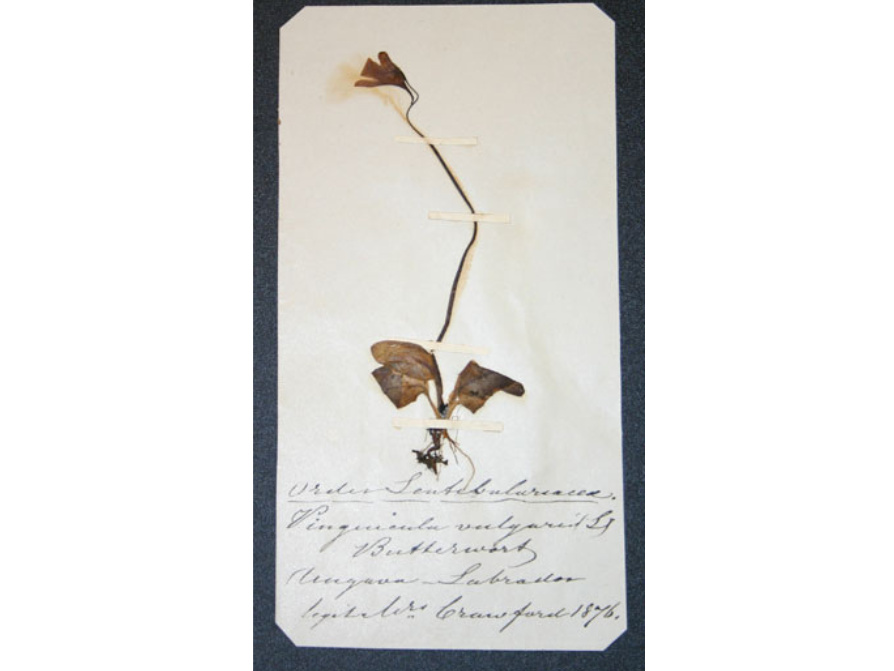

The Manitoba Museum will be hosting the NAPC conference banquet on August 9. Rather than a typical sit down dinner, attendees will be able to graze their way through the Museum’s galleries while socializing and interacting with interpreters and yours truly. I will be presenting some of the findings on my recent pollination and rare plant research as well as leading the conference tours to Spruce Woods Provincial Park and Riding Mountain National Park. The former Curator of Botany, Dr. Karen Johnson, will be leading the pre-conference field trip to the Northern Studies Centre in Churchill, Manitoba where participants will learn more about the wildflowers and whales in the region.

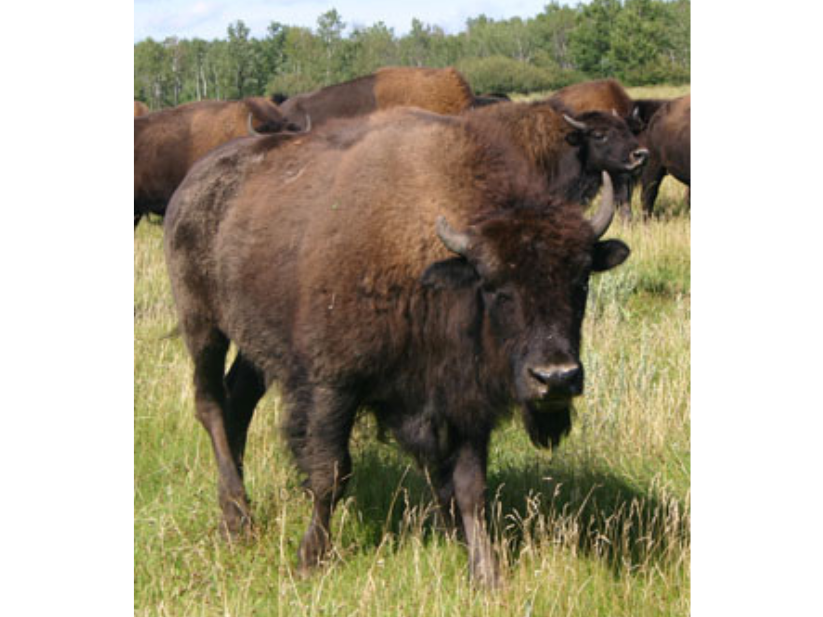

Image: The post conference field trip will go to Riding Mountain National Park, a spot where the prairie meets the forest.

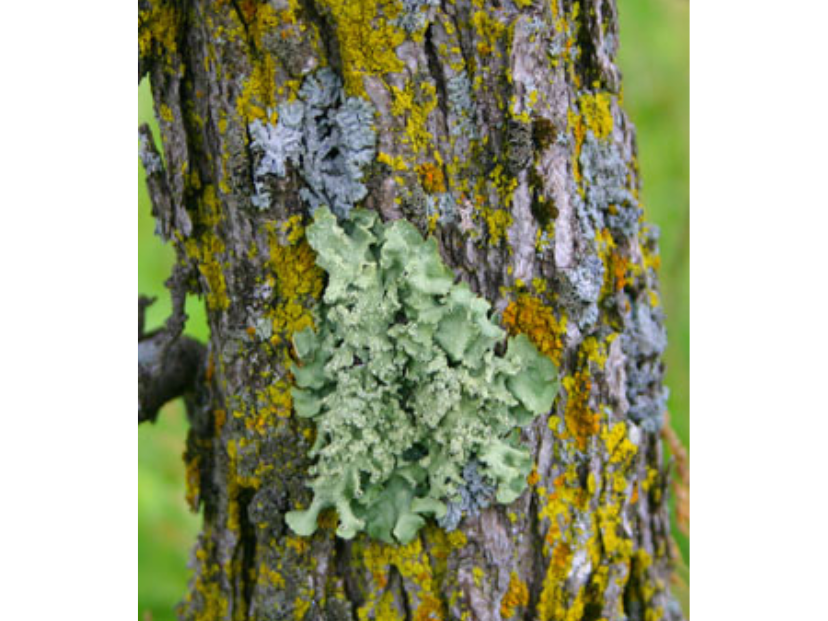

Conferences like this provide a great opportunity for professionals to meet and exchange information that will assist with their work. But it is also a chance for people who are just concerned about prairie conservation to learn more about these beautiful and intricate habitats that are now almost gone. Hope to see you there!