August is a great month for stargazing. Besides the annual Perseid meteor shower, we have some planets gathering in the pre-dawn sky which will make a nice series of photo-ops for early risers. August is also a time when many people vacation to places farther from city lights, giving them the chance to see a really dark sky. Travel during the time near new moon will maximize your dak-sky experience, but even the Full Moon rising over the city skyline can remind us of our connection to the wider universe around us.

The Solar System for August 2025

Mercury is invisible early in the month as it passes near the Sun, but reappears in the morning sky just before sunrise for the second half of August this year. The closest planet to the Sun never rises very high above the horizon before the Sun does, so you will need a clear horizon and good timing to catch it. See calendar entries below.

Venus begins the month rising about 3 a.m. local time, but slowly slips sunward over the course of the month. It passes less than 1 degree from Jupiter on August 12 and is near the Beehive star cluster in Cancer the Crab at the end of the month. See various calendar entries below for details.

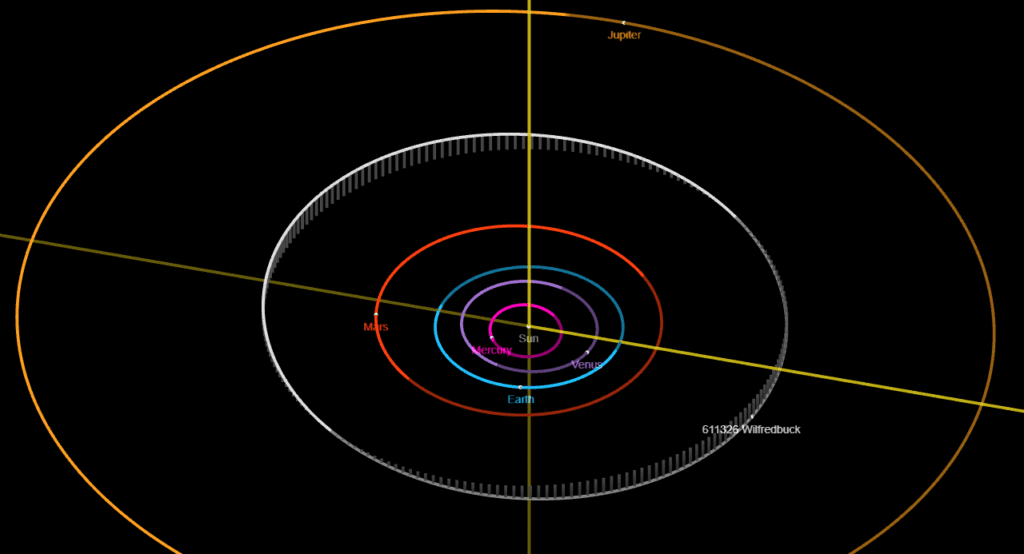

Mars is in the constellation Virgo, so low in the west-southwest that you probably won’t see it. It doesn’t slip behind the Sun until January 2026, but right now the angle of its orbit keeps it very low from northern latitudes like Manitoba. (Despite all the hype of supposed “big events” you might have heard about online.)

Jupiter rises in the northeast before 4 a.m. local time at the beginning of the month, and about 2 a.m. by the end of August. It begins to brighter Venus’ lower left, drawing closer and closer each morning until their closest approach on the morning of August 12, 2025. After this, Jupiter rises higher each morning as it moves slowly among the stars of Gemini.

Saturn rises about 11 p.m. at the beginning of August, and by 9 p.m. at month’s end, finally becoming high enough for reasonably-timed observations. Saturn’s rings are tilted almost edge-on to our line of sight, making them difficult to see in a telescope. Neptune is nearby for most of the summer (see below). The waxing gibbous Moon is nearby on the morning of August 12 (see below).

Uranus is in the morning sky a few degrees below the famous Pleaides star cluster (also known as the Seven Sisters). It is too faint to easily see without binoculars, and even a telescope shows it as a faint dot that looks just like the other faint stars. A detailed star-charting app like Stellarium is required to track it down.

Neptune is in the same binocular field of view as Saturn for the entire month, but since it is even farther than Uranus it is invisible without optical aid. Neptune requires good binoculars or a small telescope to even spot, and a large telescope to make it out as anything more than a faint dot. Again, a detailed star chart like those produced by Stellarium is required to tell which tiny “dot” is Neptune.

Of the five known dwarf planets, only (1) Ceres is close enough to be seen in binoculars or a small telescope. In August, Ceres is below and to the left of Saturn and Neptune, wandering among the stars of the constellation Cetus the Whale. You’ll need a chart like the one in the RASC Observer’s Handbook or an app like Stellarium to track it down. Ceres will be easier to spot in the fall as it gets closer and brighter.

Sky Calendar for August 2025

All times are given in the local time for Manitoba: Central Daylight Time (UTC-5). However, most of these events are visible across Canada at the same local time without adjusting for time zones.

If there’s a little box to the left of the date, you can click on it to see a star map of that event! All images are created using Stellarium, the free planetarium software.

Friday, August 1, 2025: First Quarter Moon

![]() Sunday, August 3, 2025: The waxing gibbous Moon is just below the bright red star Antares, very low in the south this evening and into Monday morning.

Sunday, August 3, 2025: The waxing gibbous Moon is just below the bright red star Antares, very low in the south this evening and into Monday morning.

![]() Monday, August 11, 2025: A busy night for observers. The waxing gibbous Moon is above and to the right of Saturn as they rise about 10 p.m. CDT. Over the course of the night, the Moon will move closer to Saturn as the pair rise higher and move across the sky. This showcases two of the most important sky cycles: the rising of Saturn and the Moon is caused by the Earth’s rotation every day, while the Moon gets closer to Saturn due to the Moon’s orbital motion around the Earth every month.

Monday, August 11, 2025: A busy night for observers. The waxing gibbous Moon is above and to the right of Saturn as they rise about 10 p.m. CDT. Over the course of the night, the Moon will move closer to Saturn as the pair rise higher and move across the sky. This showcases two of the most important sky cycles: the rising of Saturn and the Moon is caused by the Earth’s rotation every day, while the Moon gets closer to Saturn due to the Moon’s orbital motion around the Earth every month.

Also tonight and into tomorrow, the annual Perseid meteor shower reaches its peak intensity – but this isn’t a great year for it. The nearly-full Moon’s light will overwhelm most of the faint meteors. Best time will be to in the early morning hours of the 12th, in the period from about 2am until dawn. During this period you might see a dozen or two meteors per hour, if you are in a dark sky and watch the sky continuously with no breaks. If you are up this late/early, watch for Venus and Jupiter’s conjunction just before dawn (see below).

![]() Tuesday, August 12, 2025 (morning): The peak of the Perseid meteor shower is offset by the bright Moon, but you can still expect a meteor every minute or two if you’re patient. Jupiter and Venus rises in the north-northeast about 3:20 a.m. local time, less than 1 degree apart and probably tinted orange by any smoke on the atmosphere.

Tuesday, August 12, 2025 (morning): The peak of the Perseid meteor shower is offset by the bright Moon, but you can still expect a meteor every minute or two if you’re patient. Jupiter and Venus rises in the north-northeast about 3:20 a.m. local time, less than 1 degree apart and probably tinted orange by any smoke on the atmosphere.

![]() They will rise higher and be due east by dawn.

They will rise higher and be due east by dawn.

![]() Saturday, August 16, 2025 (morning): The Last Quarter Moon is approaching the Pleaides star cluster, growing closer each hour until the sun rises.

Saturday, August 16, 2025 (morning): The Last Quarter Moon is approaching the Pleaides star cluster, growing closer each hour until the sun rises.

![]() The morning of the 16th is probably your first chance to spot Mercury this season, early in the morning in the east, below and left of much brighter Venus and Jupiter. The chart shows the view at 5:45 a.m. local time; the blue circle represents the field of view shown in typical household binoculars, which will definitely help in tracking down the elusive inner planet. Over the next several days Mercury will rise higher and get brighter and easier to see.

The morning of the 16th is probably your first chance to spot Mercury this season, early in the morning in the east, below and left of much brighter Venus and Jupiter. The chart shows the view at 5:45 a.m. local time; the blue circle represents the field of view shown in typical household binoculars, which will definitely help in tracking down the elusive inner planet. Over the next several days Mercury will rise higher and get brighter and easier to see.

Tuesday, August 19, 2025 (morning): The waning crescent moon forms a ragged line with Venus and Jupiter in the pre-dawn sky.

![]() Also look for Mercury very low to the horizon just before dawn.

Also look for Mercury very low to the horizon just before dawn.

![]() Wednesday, August 20, 2025 (morning): The waning crescent has passed Jupiter and Venus, now forming a right triangle with the two bright planets in the morning sky. Above and to the left at much fainter Castor and Pollux, the brightest stars in the constellation of Geminin the Twins.

Wednesday, August 20, 2025 (morning): The waning crescent has passed Jupiter and Venus, now forming a right triangle with the two bright planets in the morning sky. Above and to the left at much fainter Castor and Pollux, the brightest stars in the constellation of Geminin the Twins.

![]() Also look for Mercury very low to the horizon just before dawn.

Also look for Mercury very low to the horizon just before dawn.

![]()

![]() Thursday, August 21, 2025 (morning): A razor-thin crescent Moon stands above Mercury as the dawn sky brightens. Look low in the east-northeast as the sky brightens. The chart to the right shows the view at 5:45 a.m. CDT; the blue circle indicates the field of view of typical household binoculars.

Thursday, August 21, 2025 (morning): A razor-thin crescent Moon stands above Mercury as the dawn sky brightens. Look low in the east-northeast as the sky brightens. The chart to the right shows the view at 5:45 a.m. CDT; the blue circle indicates the field of view of typical household binoculars.

Saturday, August 23, 2025: New Moon

Sunday, August 31, 2025: First Quarter Moon

Summer Meteor Showers

Outside of the regular events listed above, there are other things we see in the sky that can’t always be predicted in advance.

Aurora borealis, the northern lights, are becoming a more common sight again as the Sun goes through the maximum of its 11-year cycle of activity. Particles from the Sun interact with the Earth’s magnetic field and the high upper atmosphere to create glowing curtains of light around the north (and south) magnetic poles of the planet. Manitoba is well-positioned relative to the north magnetic pole to see these displays often, but they still can’t be forecast very far in advance. A site like Space Weather can provide updates on solar activity and aurora forecasts for the next 48 hours. The best way to see the aurora is to spend a lot of time out under the stars, so that you are there when they occur.,

Random meteors (also known as falling or shooting stars) occur every clear night at the rate of about 5-10 per hour. Most people don’t see them because of light pollution from cities, or because they don’t watch the sky uninterrupted for an hour straight. They happen so quickly that a single glance down at your phone or exposure to light can make you miss one.

Satellites are becoming extremely common sights in the hours after sunset and before dawn. Appearing as a moving star that takes a few minutes to cross the sky, they appear seemingly out of nowhere. These range from the International Space Station and Chinese space station Tianhe, which have people living on them full-time, to remote sensing and spy satellites, to burnt-out rocket parts and dead satellites. These can be predicted in advance (or identified after the fact) using a site like Heavens Above by selecting your location.