By Carolyn Sirett, Conservator, and Lee-Ann Blase, Conservation Volunteer

We have all seen those lifeless mannequins looking sad and lonely in a store’s window front, longing for the next wardrobe change of a new season. Here at the Manitoba Museum we like to give our mannequins a bit more attention to detail compared to their retail cousins, what some might call, a full spa treatment!

Humans are uniquely different from one another, and our clothing choices are also uniquely different, from size to shape to style. These human qualities are well represented in our historic textile collection, and when displaying these garments, every detail is assessed to ensure its preservation.

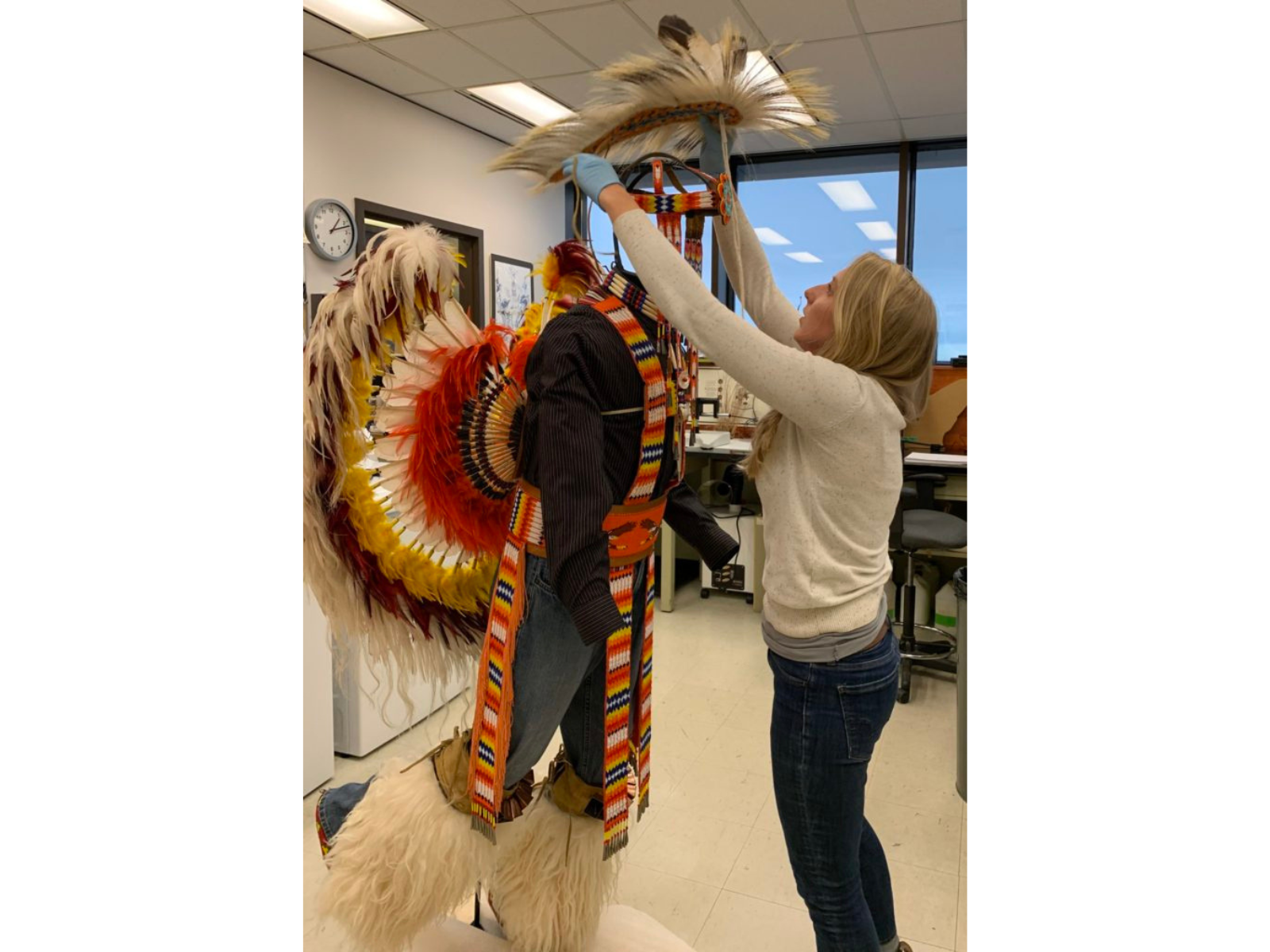

Dressing a museum mannequin is the opposite of fitting a living person. Instead of fitting the clothes to the person, the mannequin is made to fit the clothes. Many of the mannequins we use at the Museum have been custom made by our conservation department using conservation-quality materials. We first begin by measuring the waist, chest, neck, arm, and leg lengths. The mannequin form is then either trimmed down, or padded out with polyester fibre to reach the required dimensions to properly support the clothing.

Once the basic form is made and covered with a suitable fabric, we begin to dress the mannequin. This is where historic photographs are useful to see how the outfits were worn, and to bring a little more personality to our frozen foam bodies. Edith Rogers’ cotton-crocheted tea gown, displayed in the Winnipeg Gallery, is a good example of using research to determine the best fit. A tea gown bridges the gap between dress and undress as a corset is not worn with it. Research shows only an upper-class woman could have afforded this type of dress among their ball, dinner, reception, and afternoon dresses.

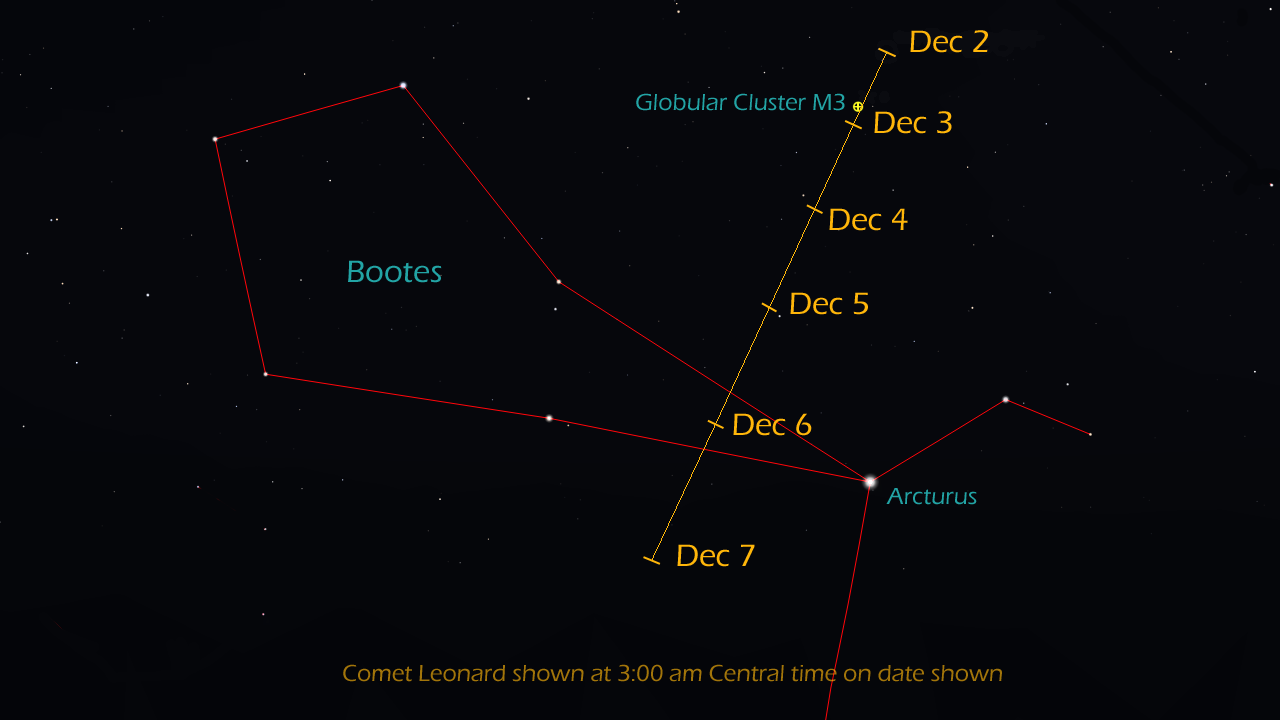

A similar style dress from a 1913 Eaton’s of Toronto catalogue was used as a reference when building the mannequin for the Edith Rogers dress.

Image: Eaton’s Spring and Summer Catalogue, No. 106, 1913

When this dress was chosen for display it first needed to be stabilized in the conservation lab with a fine net in the bodice and a few minor tear repairs. In order to make this garment appear as it would, we added a petticoat from the Museum’s collection to help support the textile. With the petticoat slipped over the custom form, then carefully sliding the dress on and using acid-free tissue to fill any gaps – voila – the tea gown was ready for exhibition.

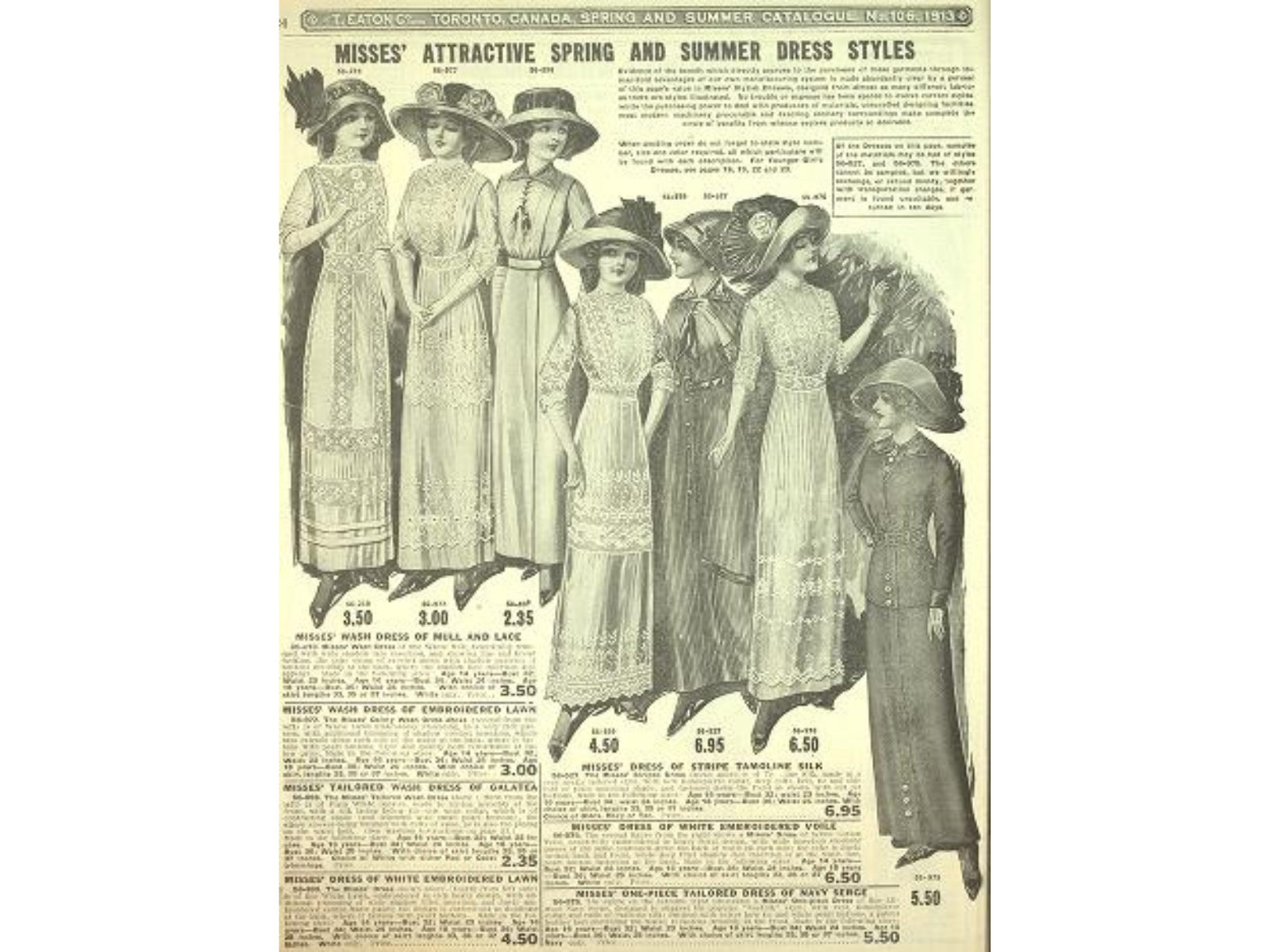

The last part of dressing a mannequin is in the finer details. The arms, hands, legs, waist, and head all need to be positioned. For the modern Pow Wow dancer in the renewed Prairies Gallery, the Curator wanted to evoke the idea that the mannequin is dancing, to look as if the mannequin is in-motion. When trying to imply movement, it can be difficult to balance the mannequin as a structure, but also to balance the preservation of the artifacts that are being displayed.

On your next visit to the Museum, hopefully you are able to see some of these fabulously fitted forms.

Making final adjustments to the mannequin in the conservation laboratory.

Image: © Manitoba Museum

One of 22 custom mannequins created by Conservator Carolyn Sirett and installed in the new Prairies Gallery.

Image: © Manitoba Museum/Ian McCausland