By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Beginning in 2012, The Museum’s curators worked together to plan exhibits for the Bringing Our Stories Forward project (BOSF). As we travelled around the grasslands region to prepare ideas for our new Prairies Gallery, we developed a list of topics that would be essential for a representation of this region. We rapidly agreed on some things that had to go into the Gallery: prairie vegetation, the importance of wind, Indigenous prehistory (and most particularly mound-building cultures), and several other topics. One of these was fieldstone.

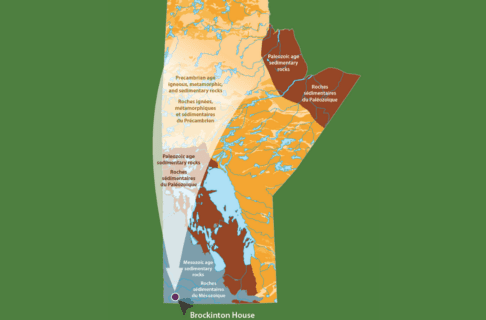

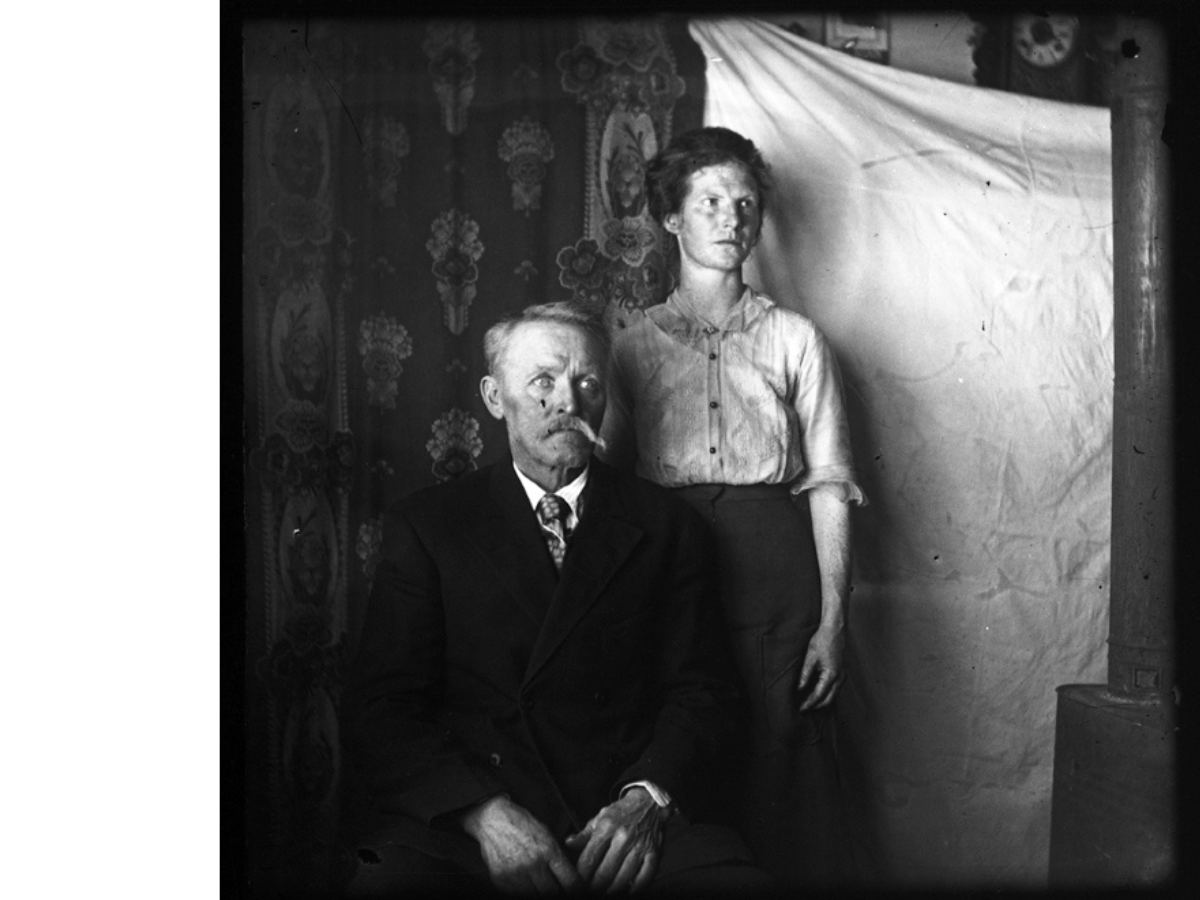

A wall of the Brockinton house shows some of the geological variety of fieldstone types.

What is fieldstone, and why did we think it was essential?

When European settlers arrived on the prairies, they wanted to build permanent houses and other buildings. They were now in a region where there were almost no trees away from the river valleys, so material for wooden houses could be scarce. Many settlers came from parts of Europe where houses were built from stone that was quarried from solid bedrock, but on the Manitoba prairie the bedrock was either buried far below the land surface, or it was soft Cretaceous shale that was useless as a building stone.

There was however, a building stone resource that was readily available: loose fieldstone boulders, which lay on the land surface or could be readily found by digging near riverbanks. Fieldstone is a mixture of many kinds of stone. These stones formed as bedrock at different times, under varied conditions, and include igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rock types.

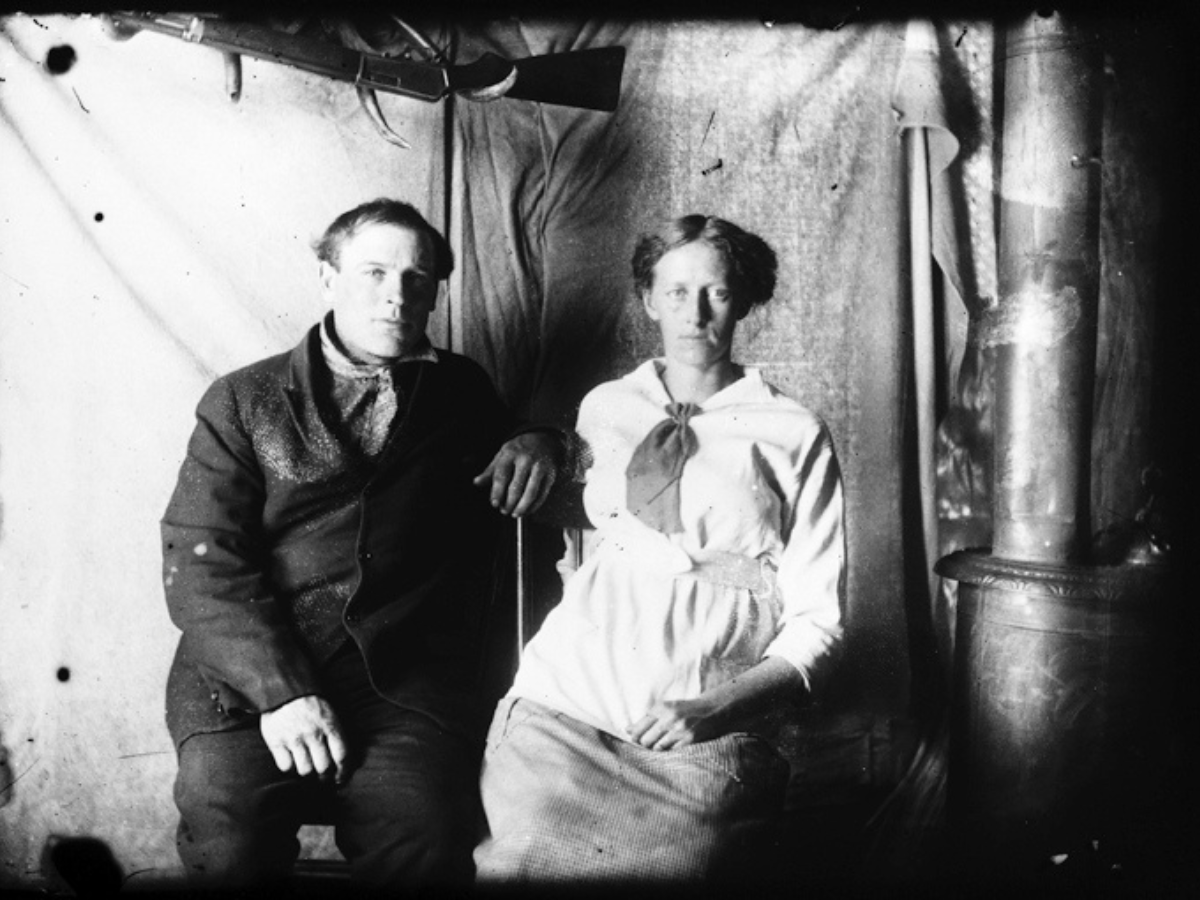

Some fieldstone structures in southwestern Manitoba are much grander than the Brockinton house. These photos show St. Paul’s United Church in Boissevain, built as a Methodist church in 1893.

Doorway of St. Paul’s United Church in Boissevain.

Like the settlers, fieldstone had immigrated to the prairies. During the Ice Age (Pleistocene Epoch), huge glaciers covered Manitoba. Glacial ice flowed southward, pulling blocks of stone out of solid bedrock. Blocks (glacial erratics), left behind when the ice melted, are used as fieldstone. Most fieldstone thus originated far to the north of where it is found today.

Since fieldstone was a distinctive natural material seen across many parts of the prairies, and since it was used by settlers when they built many of the early buildings, it was clear to us that the fieldstone story should be included in our Prairies Gallery. We already planned to build an exhibit about the Brockinton National Historic site, a significant precontact bison kill site in the Souris Valley south of Melita, so it made sense that we also create an adjacent exhibit that would represent a wall of the Brockinton house, a late 19th century structure that sits at the top of the slope above the archaeological site.

But how could we build this exhibit? Stone is really dense, and a mass of solid stone would have been far too heavy to be supported by the floor in our gallery space. Stone is also not really a topic that would have been suited to an animated video like our beautiful Prairies Mural Wall, and a flat panel display would have been just that: flat. We needed some way to allow visitors to observe and touch the genuine stone, in a setting that imitated a real fieldstone wall.

Fortunately, in our various travels around southern Manitoba we had met Todd Braun, a stonemason who works in the Altona area. By consulting with Todd and with our exhibit design team, a plan took form: a frame would be fabricated from steel clad in plywood, and Todd would prepare the stones to attach to that frame, reducing their weight by slicing them thin.

Todd and I selected stones to represent the great variety of fieldstone seen in southwestern Manitoba. Many of these came from boulders and cobbles that Todd had found during his visits to various gravel pits. A few were rocks that we found together, and in one or two instances I went to other geologists to request examples of very particular rock types.

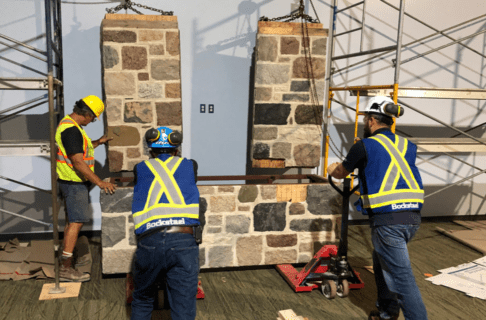

Once we had agreed on the stones to be used, Todd prepared them using traditional techniques, breaking each rock with a hammer until it had a blocky shape. These blocks were laid out in their approximate relative positions for the wall. After a fitted layout was achieved, Todd patiently took each block and trimmed it with a saw so that the visible surface was effectively a “veneer” with only a few centimetres of thickness. These veneers were then attached to the steel and plywood frame using adhesives and metal hardware, and the space between them was covered in traditional mortar. The “corner stones” were a particular challenge, since they had to be cut in such a way that they would look like solid three dimensional blocks once the wall was assembled.

To allow the wall to be assembled in Todd’s workshop prior to its installation in our gallery, the frame was actually built in three sections. This made each piece light enough to be readily moved, and small enough to fit through the smallest doorway between the Museum’s loading dock and our new Prairies Gallery. Very early one morning, Todd arrived at the Museum with the completed wall sections on his trailer. These were hoisted into the loading dock, and rolled through the Museum to the wall’s permanent gallery location. Todd and our construction team had created an ingenious hoist system that would allow each upper wall section to be lifted into position on the base section. Once the wall sections were in place, they were bolted together, and Todd covered the joins with fresh mortar.

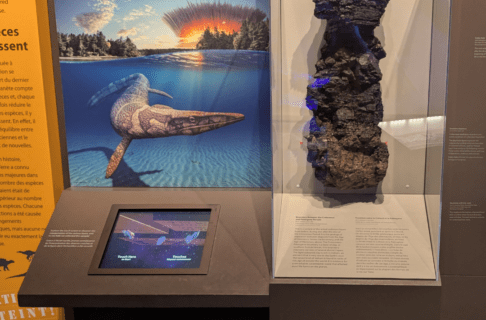

The finished wall looks very much like the walls you can see at Brockinton House and on other buildings in southwest Manitoba, and it beautifully demonstrates both fieldstone construction and the geological variety of this fascinating material. As is the case for some other Museum exhibits, there is no evidence of the incredibly complicated and lengthy development and construction process that allowed this structure to “look like the real thing.”

The finished wall is surrounded by interpretive materials, telling the fieldstone story.