Posted on: Monday September 28, 2015

As a child, the Manitoba Museum was my favourite field trip destination. I loved it all, but my favourite part was the Urban Gallery- particularly Madame Taro’s small apartment, which I thought was quite glamorous. Visits to the museum— either with classmates or family— activated my interest in history and museum work, and this summer I was given the opportunity to join the team through the Young Canada Works program as Collections and Conservation Assistant.

One of the first projects I took on was identifying locations for human history artifacts whose locations are “unknown” in the database – 527 artefacts, to be exact. It could be summed up as a glorified treasure hunt. I spent a good few weeks going through the human history storage room— climbing up ladders, rifling through drawers, looking for catalogue numbers on hundreds of artifacts— and finally whittled the number down to 188! This was certainly one of my favourite projects of the summer. It was really fascinating to explore the variety of objects in the collection – everything from night caps to an Oh Henry bar package.

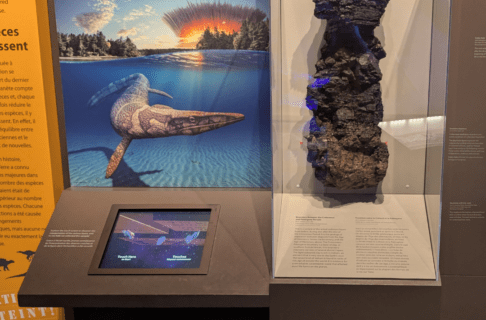

Throughout the summer I performed various forms of preventive conservation. At the end of each month I went through the galleries, labs, and storage vaults throughout the museum to take temperature and humidity measurements, as well as check the bug traps (yikes!). In August, a few of us went down into the hold of the Nonsuch to take taper gauge and trammel rod measurements to determine if the wood of the ship had expanded or contracted in the last six months. Even being on the ship for a couple hours felt a bit claustrophobic – I can’t imagine sailing for months at a time! In addition to these larger projects, I made boxes, altered mannequin forms, and recovered the bales in the Nonsuch gallery. The skills I had learned in 8th grade Home Economics finally paid off.

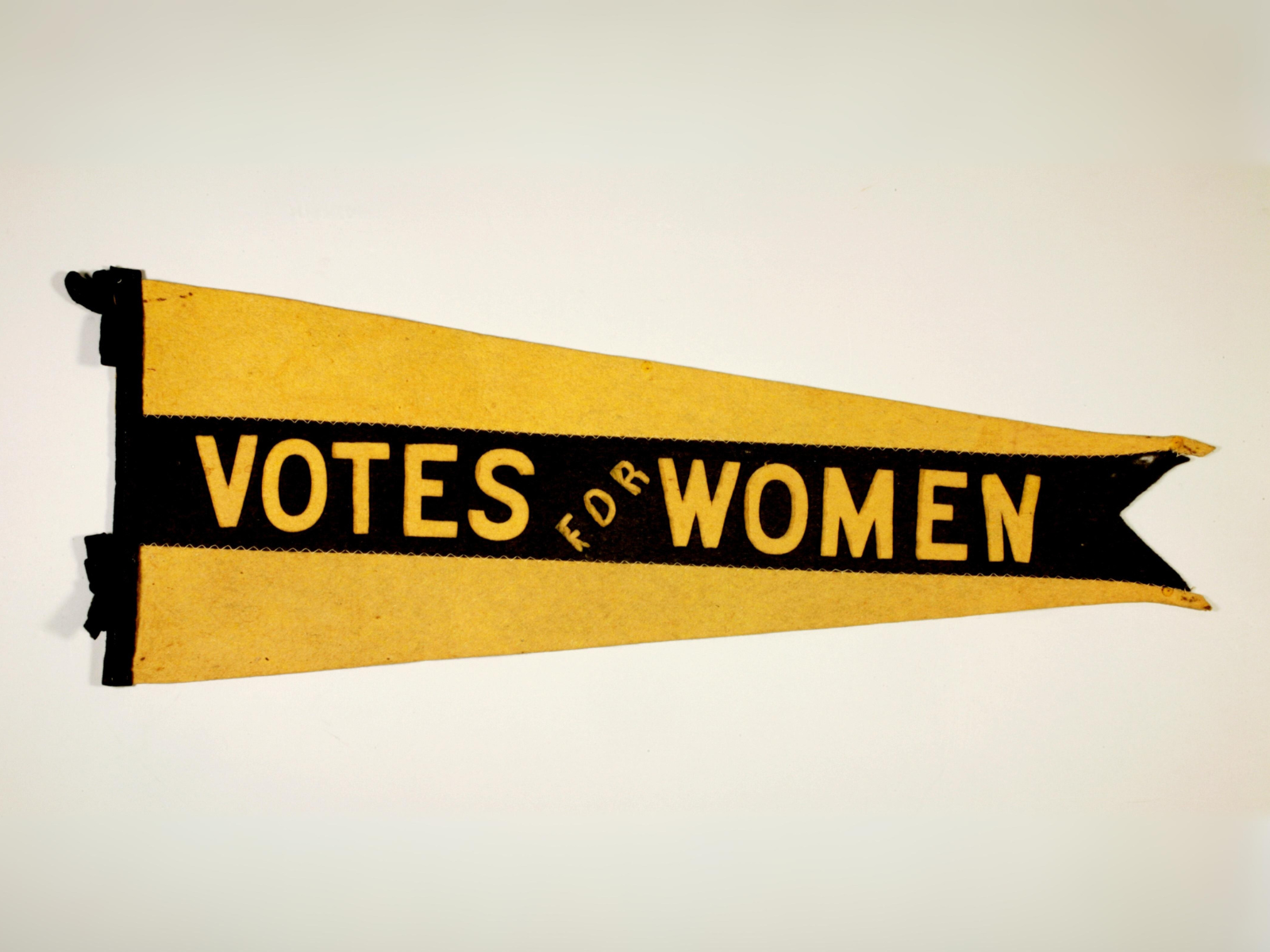

Perhaps one of the coolest things I did this summer was make a replica of a felt pennant for the upcoming “Nice Women Don’t Want the Vote” exhibit (which potentially thousands of people will see – no pressure!). Because the original artifact is quite worn and faded, a replica is more suitable to send along with the travelling exhibit to prevent further damage. Although I was a bit concerned about my lack of sewing and crafting skills, I am incredibly happy with and proud of the final product. The theme of the exhibit—women’s suffrage in the early 20th century—has been an interest of mine for quite a few years, and to be involved in the exhibit in any way was really incredible.

I had a great time at the museum this summer and was able to work on projects in many different areas of collections and conservation. The skills I built on and developed will no doubt open more opportunities for me in my (hopefully) museum-based future. The entire experience—the work and the people—was incredible, and I hope to be back here in the future!