Posted on: Thursday January 31, 2013

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Winnipeg has a long and complicated history of museums featuring natural history collections. Our current museum was a centennial project, opened in 1970, but we are very fortunate that we possess vestiges of those earlier museums, such as minerals from the Carnegie Library collection and mounted animals from some of the early taxidermists. The most visible and best-documented of these “inheritances” are pieces that were exhibited in the old Manitoba Museum, which occupied part of the Winnipeg Civic Auditorium from 1932 until about 1970.

We have a good record of specimens from the old museum because they were numbered, with the numbers listed in a book. We also have good knowledge of how some of these pieces were exhibited thanks to a set of photographs that are digitally filed at the Museum. I am not certain of the dates of these photos; some seem to be from the 1930s when specific exhibits were being installed, while others are from the 1940s or 1950s and show finished exhibits.

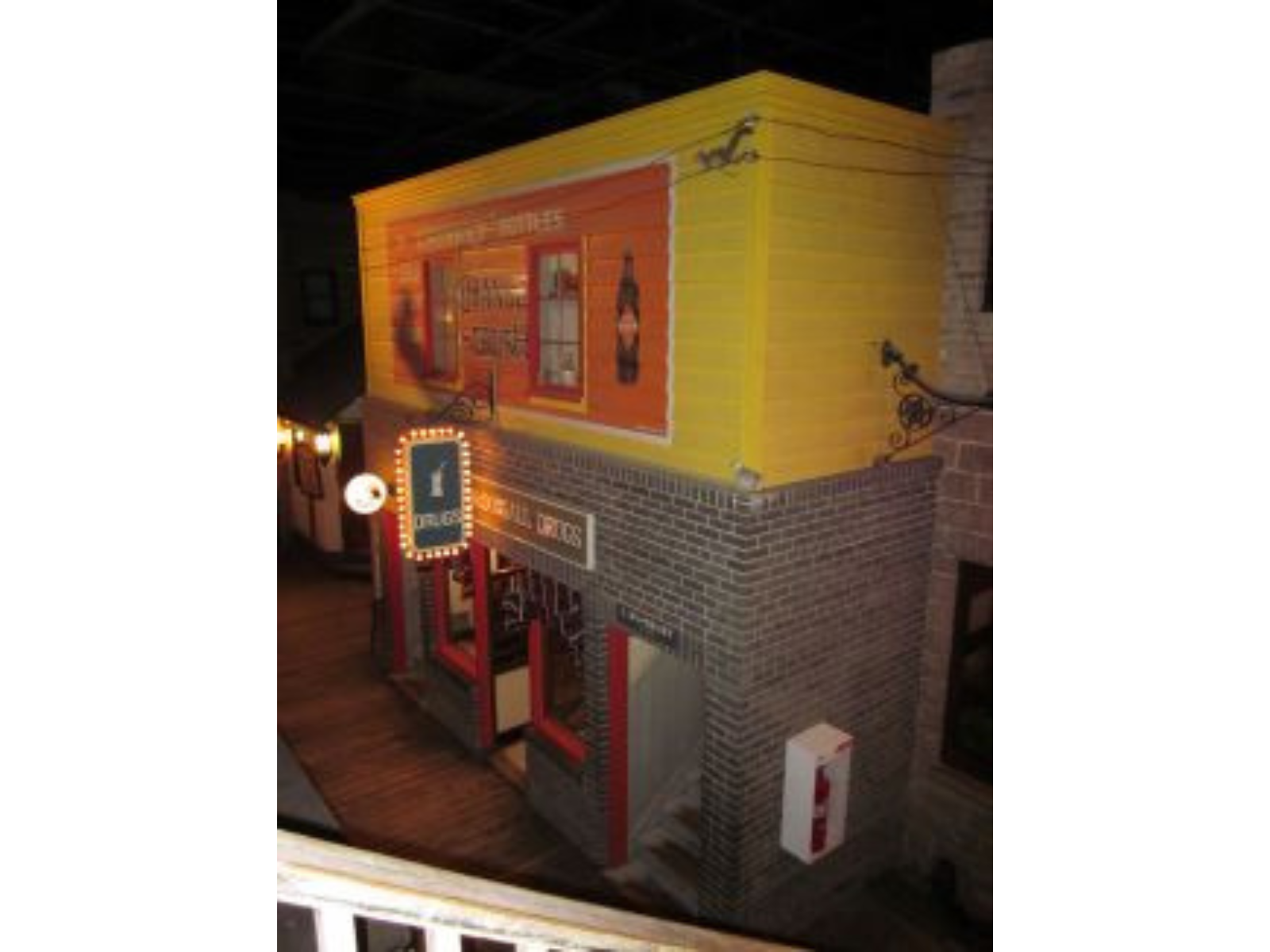

The old museum was not large, but it was clearly a pleasant place to spend an afternoon examining cabinets of archaeological artifacts, First Nations clothing, stuffed birds, and fossils. It was very much a “cabinet of curiosities” of the old school, and a good one. Sometimes when I look at these photos I feel a bit sad, and wish that we had been able to keep that old museum as well as building this newer one.

Image: Some of the exhibits at the old Manitoba Museum.

In a way, though, we have kept some of that old Museum, in the specimens and artifacts we inherited. It is intriguing that, even after all this time, many of those fossils are still the best examples we have for particular groups, and several of them are in the Earth History Gallery or have been selected for temporary exhibits. The most obvious of these is our mounted Cretaceous plesiosaur, Trinacromerum kirki.

The plesiosaur as exhibited in the old Manitoba Museum after 1937.

The plesiosaur on exhibit last week.

The plesiosaur is now exhibited near a mosasaur skull, with beautiful reconstructions of the pterosaur Nyctosaurus suspended above.

This specimen, collected from the Manitoba Escarpment near Treherne in 1932, was a highlight of the old museum. After several re-mountings (including a more accurate replica skull), it remains a focus of our Earth History Gallery today. Skeletons of large extinct creatures never go out of style, but what other fossils can also be traced to the old museum?

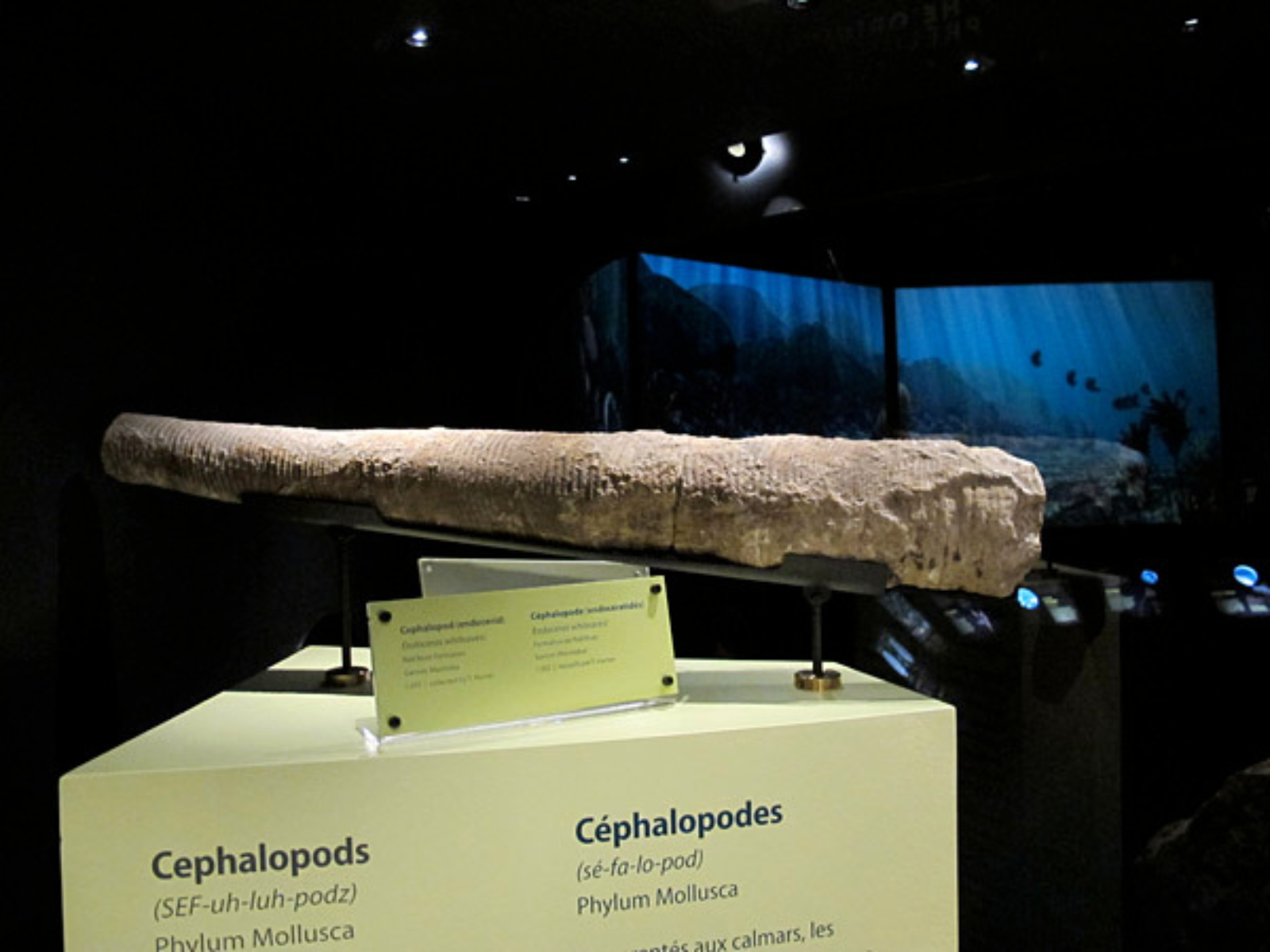

The exhibits there featured some beautiful specimens of cephalopods (relatives of octopus and squid) of Ordovician age (about 450 million years old). Ordovician cephalopods are familiar to many Winnipeggers because cut sections through these fossils are often seen in Tyndall Stone walls. Although the cut fossils are common, complete cephalopods are very rarely found nowadays, because the stone is cut directly out of the quarry walls.

In the early years of quarrying, however, the work was done by hand. Three-dimensional fossils were extracted more commonly, and as a result many of our best large Tyndall Stone fossils come from the old collections. This is particularly striking in the Ancient Seas exhibit, where the finest endocerid cephalopod is one that was on exhibit in the old museum, and where some of the other fossils also came from old collections.

Ordovician cephalopods in the old museum. We have all of these specimens in our collection; look at the next photo for another image of the largest one!

The endocerid from the old museum is one of the highlighted specimens in the Ancient Seas exhibit.

Other specimens from the old museum make appearances almost every time we do a temporary exhibit in the Discovery Room, featuring geology or paleontology pieces. Right at the moment, the cephalopod case in our Marvellous Molluscs exhibit includes a pair of fossils from that source. Looking at the old photographs, I was fascinated to discover that two “old friends” that shared a case in the old museum are right beside one another in this current exhibit!

There is something very pleasing about seeing them together like this, 70 years or so after that previous photo. In this way at least, the old museum lives on.

A group of Tyndall Stone cephalopods in the old museum. Note the specimens at top right and bottom left.

Part of the cephalopod exhibit in Marvellous Molluscs, with the two old museum specimens in front.