Posted on: Monday October 29, 2012

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

It is 7 am, somewhere on the curves near Woodlands, Manitoba, and the sky is still completely dark. The rain is coming down harder now and approaching headlights are blurred by the slicked windshield. I usually love the open road, but this driving is far from fun.

We are well past Lundar before the late dawn. The traffic has diminished now and the rain has eased a bit, but the wind is rising. At the Ashern Petro-Can we stop for fuel: unleaded for the Jeep and junk food for the humans. Ed takes over the wheel for the next monotonous stretch.

Today we plan to go to William Lake, well north of Grand Rapids, then back to Winnipeg before the evening has progressed too far: a drive of 1000 kilometres or so. Why are we subjecting ourselves to this, in this unpleasant wet weather?

Tamaracks and spruce south of Grand Rapids.

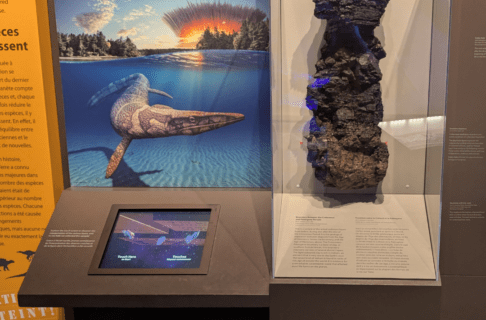

Last summer, in the beautiful warmth of August, we found a greater quantity of interesting rock than we could safely haul back to Winnipeg at the time. In particular, two splendid specimens we discovered on the last day had to be left lying on the outcrop. These were very large slabs, both of which remarkably preserve portions of what appears to be a channel on an ancient tidal flat, filled with fossilized jellyfish! They are the sorts of unusual pieces that the Museum really needs, because they would be very useful for both exhibits and research, and I was determined that we would get them back to Winnipeg before winter.

Then the autumn got busy, very busy, and the trip to retrieve these pieces was placed on the back burner. I began anxiously scanning the calendar and weather forecasts, and determined that October 18th would be the ideal day to make this trip, assuming that it didn’t snow first! Field paleontology is very much a climate-dependent occupation, and we have done this trip north so many times that we know when winter is likely to close our window of opportunity.

Image: The slabs as they appeared when we found them last summer. Both show portions of a large channel that is filled with fossil jellyfish.

So now Ed and I are in a rented Jeep, heading north past the black spruce, yellow tamaracks and bare-branched aspen. At Fairford there is a tremendous flow of water past the bridge, and the summer’s pelicans are nowhere to be seen. Over the lip of the St. Martin impact crater the road is empty and desolate. Much of it has been repaved recently and is beautifully smooth, but toward the Pas Moraine we hit a rutted stretch and Ed has to slow down to avoid hydroplaning on the long pond under our right-hand tires.

At the old burn south of Grand Rapids, I recall the exact place where we saw a lynx last autumn. All self-respecting lynxes are clearly hiding out in the dense brush on this nasty wet day!

We stop again at Grand Rapids for fuel. There is more than a half-tank remaining, but it will be a long drive before we are back here again and it is best not to take chances. Fortunately there is someone on duty at the Pelican Landing gas station, because it really wouldn’t be pleasant to “self serve” in the pouring rain.

I am driving now, up the curves and past the beautiful lakes of the Grand Rapids Uplands. We arrive at William Lake just a bit after noon. Now there is snow blasting in on a north wind, and the thermometer is reading a balmy +1 C. Navigating slowly across the scree, I can see the two large slabs lying right where we left them. After six hours of driving, we now have 15 minutes of physical work: fold down the seat, spread the tarp, slip on gloves, and manhandle the rock into the back. We pause for a few photos, and are grateful that the outdoor work is so brief, because our hands are already frozen and numb.

I move the smaller slab (photo by Ed Dobrzanski)…

… while Ed freezes his fingers taking photos.

Seeing these slabs in the Jeep, it is pretty clear why we couldn’t fit them in with the other fossils and gear during the summer!

Our hands thaw as the Jeep crawls back toward the highway. At the Grand Rapids bridge a solitary pelican flies past; perhaps this one was asleep and missed its flight south? Now we a bit of time for lunch at the Pelican Landing restaurant: smoked meat sandwiches, cream of celery soup, and coffee have never been more welcome. We say hello to a few familiar faces; I guess we are becoming “fixtures” here, but I am not sure when we will manage to get back again. It is an appropriate day for this sort of sombre thought.

Now it is time to confront the long road home. As it turns out, the weather for the drive back will be slightly more pleasant, and we cruise smoothly into Winnipeg just as darkness is setting in. It has been a lot of driving to pick up a couple of rocks, but very worthwhile: within a week it will be winter in the Uplands, and if the pieces had been left until spring they would have been heavily weathered and damaged by the winter’s extreme frost and ice.