Posted on: Monday October 24, 2011

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Around the Museum this morning, people are excited that Justin Bieber and Selena Gomez visited over the weekend, enjoying a private dinner aboard the Nonsuch. I am pleased that they liked the Museum, and that they were particularly interested in Ancient Seas. But there is another piece of external attention that I am just as pleased about, even if it is unlikely to ever attract a story on Entertainment Tonight. In fact, I would have to say that I am “chuffed.”

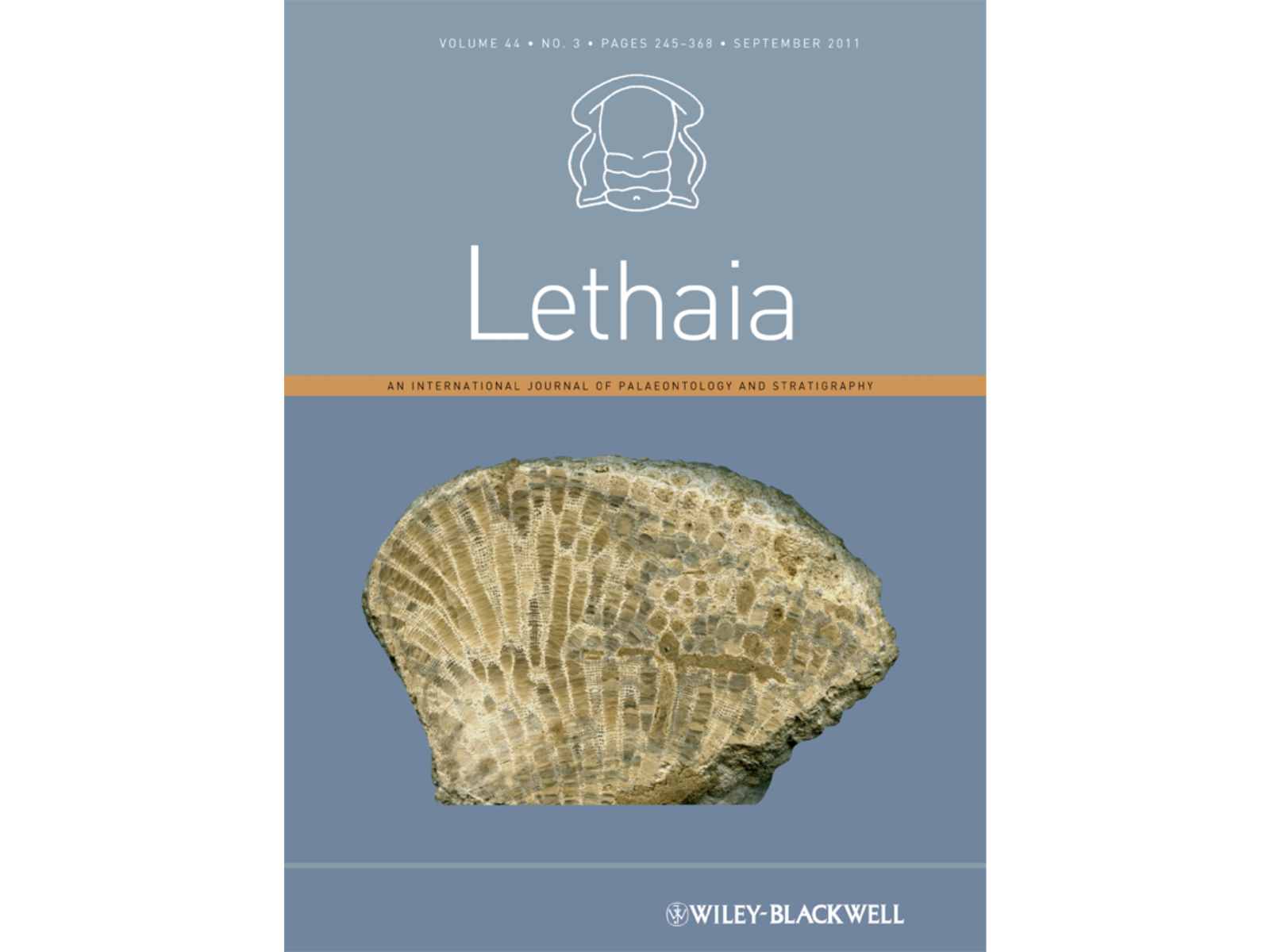

A couple of weeks back, my colleague Bob Elias and I were contacted by the editors of the paleontological journal Lethaia, who were wondering if we might have photos suitable for their cover. It was time for a change from the ammonoid that had graced the cover for several years, and since there were going to be papers about fossil corals and reefs in a coming issue, they were looking for a suitable image of a Paleozoic coral.

So Bob and I scouted around to see what we had. I had some very good photos of Manitoba specimens, but they were all colour slides shot in pre-digital times and I knew from experience that it is hard to get a really first-rate image from a scanned slide. So I delved into the collection, pulling out some of those same specimens and placing them onto the flatbed scanner. With the scanner the pixel count is virtually infinite, and after a bit of editing I was able to get images that seemed to work. Bob and I selected a variety of photos from what we had, and sent them off to the editors.

Last week we received a message with this cover mock-up:

There, snuggled into the standard Lethaia cover, is one of the Ordovician tabulate corals from Garson, Manitoba. This is a coral generally identified as Calapoecia sp. cf. C. anticostiensis Billings; the image is of a colony that had been vertically cut and fine polished. The rock unit in which it occurs is the Upper Ordovician (Katian) Selkirk Member of the Red River Formation. This unit, more commonly known as Tyndall Stone, is quarried at Garson and used as a beautiful building stone all over Canada. The coral specimen actually came from rubble heaps at the stone quarry; what could possibly be more representative of this region?

Image: This vertically cut and polished colony of Calapoecia records growth of the coral animals on the ancient tropical seafloor. The horizontal band of sediment to the right of the middle represents an interval in which the animals in part of the colony had died off. This was followed by regeneration as new polyps grew to colonize the “dead” surface (The Manitoba Museum, I-3413).

Maybe this won’t attract hundreds new visitors to the Museum, but it is still nice to have since it will make our existence known to people in very distant places. It is good to see our collections out there; they are so often useful in ways that we have not even thought of!