Posted on: Tuesday June 28, 2011

Imagine yourself in the basement of the science building at Brandon University, on a Saturday morning in the summer. The place seems to be abandoned, with the hum of the lights and ventilation the only sounds you hear. Opening a door, you walk into a quiet, darkened laboratory. A curtain closes off one end of the room, and something behind that curtain emits an eerie blue-green glow.

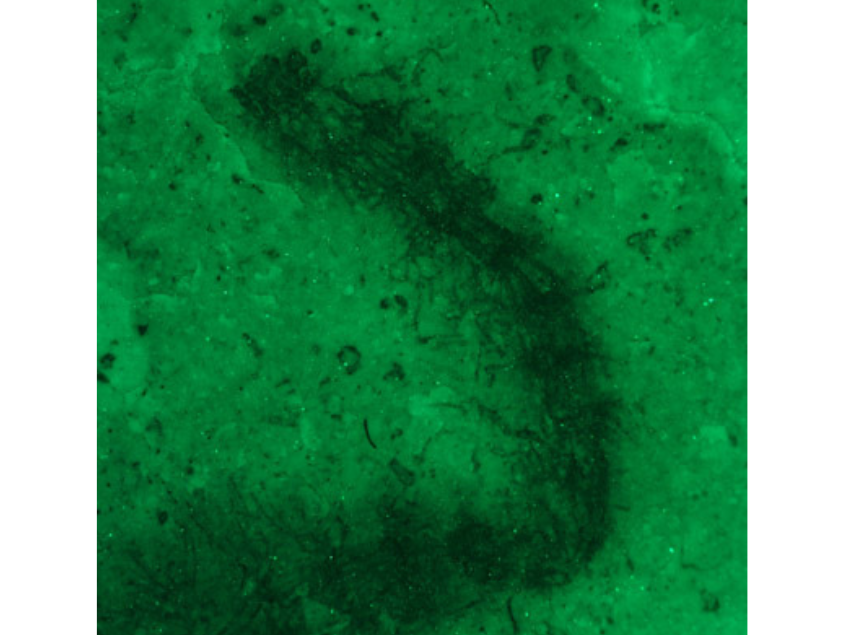

An Ordovician fossil seaweed from Airport Cove, Churchill, photographed with UV radiation and a green filter.

Tiptoeing closer, you observe that there is a man behind the curtain, huddled over a pair of computer screens. Beside the computer, a scientific instrument is producing a blinding bluish light. Who is this mad scientist, and what are the nefarious schemes that bring him here at this strange time?

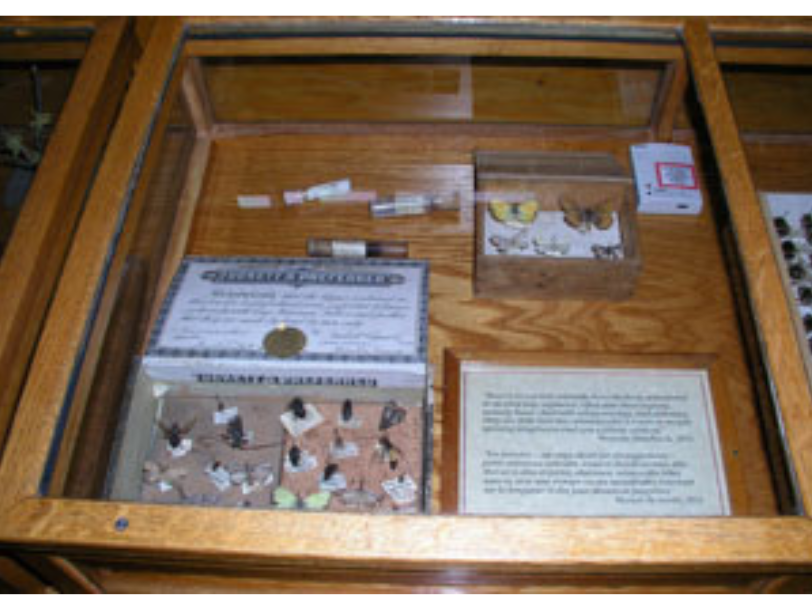

Actually, the man is me, and I am looking at fossils. I travelled to Brandon to use the fine microscope in their Environmental Science Laboratory, by kind invitation from Dr. David Greenwood. At the Museum we have good microphotography equipment, but I had reached its limits trying to sort out the fine structure of some of our unusual fossils. When I visited Brandon a few months ago, David suggested that I might want to try their scope system, which was set up with the aid of a large grant from the Government of Canada.

The digital camera on the binocular microscope feeds into a dual display computer.

The panel on the left screen allows you to select the area being photographed, and to spot focus the image. The right screen shows the captured images.

So a couple of weeks ago, I hauled a variety of fossils out to Brandon, and spent a few days on the binocular scope seeing what it could tell me. It is a lovely Olympus setup, with full digital image capture and focusing, and a variety of illumination options. It took me quite a while to figure out how to get good photos of our material, but once I had it sorted I was very happy with what it could do.

My research colleagues and I are trying to sort out the fine structure of some of the unusual fossils we have collected in the Grand Rapids Uplands and the Churchill area, things like horseshoe crabs, eurypterids, and jellyfish. I felt a bit rushed trying to look at the many specimens of these, but in several instances I was struck by the sudden realization that I was seeing features that I had never been able to make out before.

Some of the legs of an Ordovician eurypterid (“sea scorpion”) from the Grand Rapids Uplands.

Spectacularly preserved cuticle of an Ordovician arthropod (joint-legged animal) from Airport Cove, Churchill.

The front image is a UV photo of the central part of a fossil jellyfish from the Grand Rapids Uplands.

This sense was particularly striking when I was able to image specimens under ultraviolet. Although none showed the bright fluorescence I had hoped for, some of the images were very different from those under standard lighting. With their odd greenish glow, I sometimes felt as though I was seeing the ghosts of the long-departed creatures.