Posted on: Tuesday June 17, 2014

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

Those of you who are familiar only with the exhibits and the other “front end” parts of the Museum might be surprised at the constant changes that take place in the hidden parts of the institution. You might think that the dusty backrooms would remain the same from decade to decade, but really it is a whirl: exhibits are built in the workshop and moved out onto the floor, new plant and animal replicas and models are made by the artists, and specimens and artefacts are constantly cycled through the labs and storerooms of the Museum tower.

This state of change is true on the research side of things, too. The curators spend quite a bit of time studying our collections, but the collections are very large and many of the objects are far outside our own expertise. Since the Museum serves as a resource for researchers from outside, we often receive research visitors who wish to study particular parts of the collection. These visits are extremely beneficial to both parties: the researchers have an opportunity to study some of our remarkable material, and the Museum benefits from their expert identifications of our collections, and from the sharing of new knowledge with the scholarly community and the general public. Our collections and exhibits are improved by these studies!

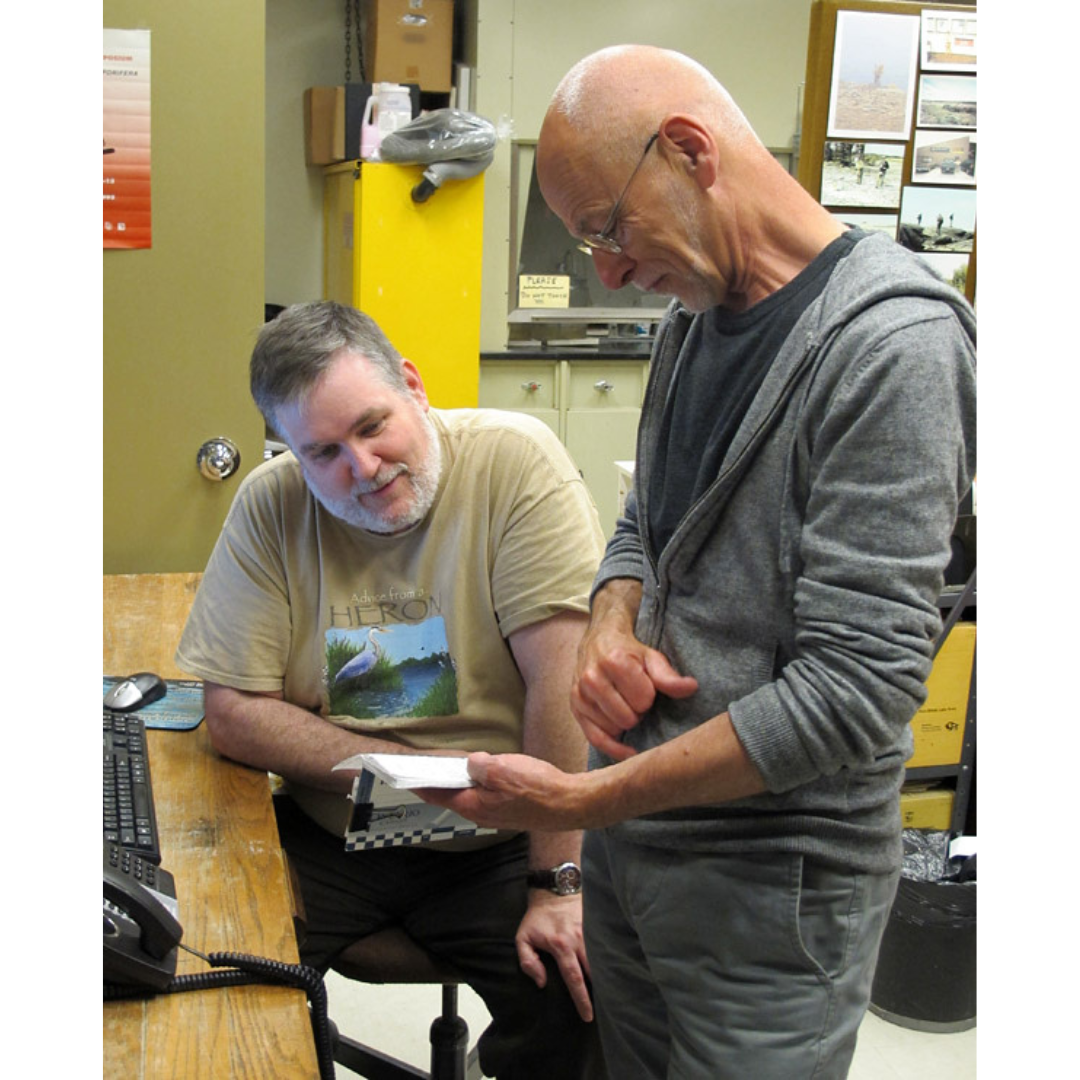

Michael Cuggy (L) and Dave Rudkin discussing specimen notes.

Research visits tend to occur in cycles or waves; researchers from out of town, in particular, seem to plan extended study visits for the summer months. This may be partly because many of them work at universities and other teaching institutions, and the summer is the interval in which they get a break from day-to-day teaching responsibilities. In the case of The Manitoba Museum, it might also have something to do with the climate, as some people from outside the prairies have the (mistaken?) impression that Winnipeg’s weather is something less than tropical from November through April.

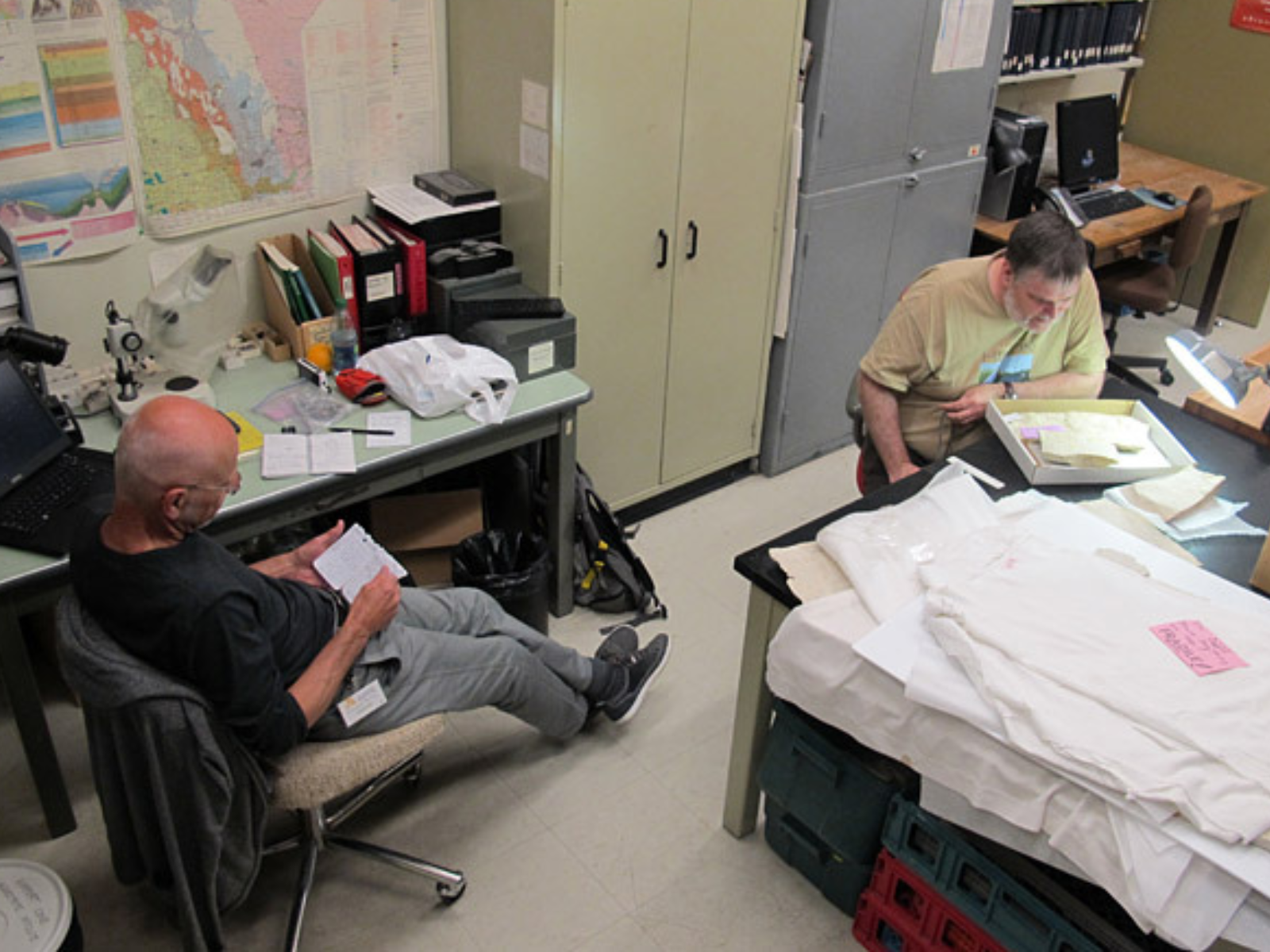

Michael Cuggy contemplates a eurypterid specimen.

Right now we are into that summer stage, and this week I have the pleasure of receiving research visitors in the lab. My friends and colleagues Dave Rudkin (Royal Ontario Museum) and Michael Cuggy (University of Saskatchewan) are here to spend some serious time with the fossil eurypterids (“sea scorpions”) that we have collected from Ordovician age rocks in Manitoba over the past dozen years or more (these rocks are about 445 million years old).

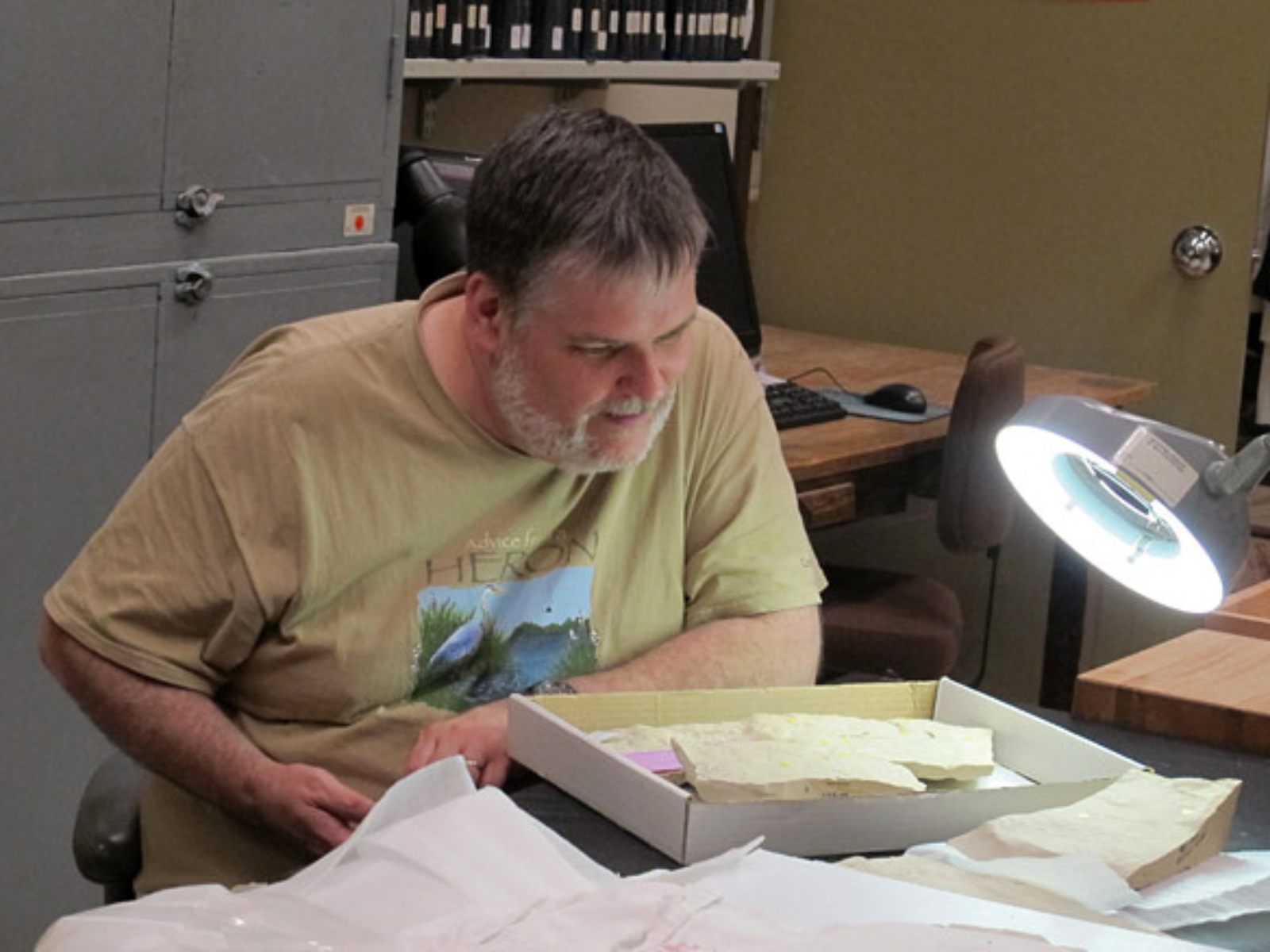

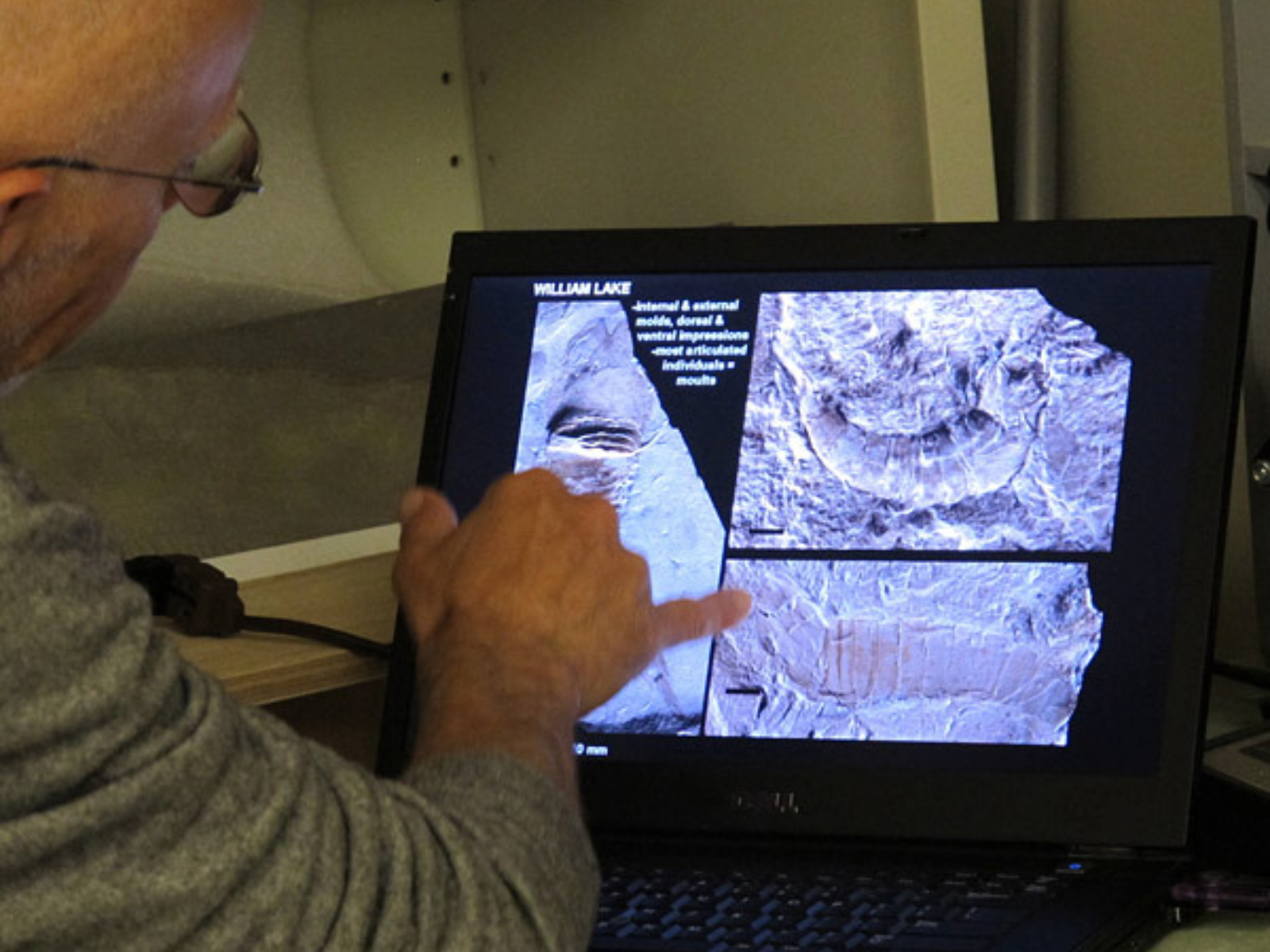

In this particular case, Dave and Michael are collaborating with me on the project, which is particularly nice as I receive visitors and also get to contribute to the research myself. Eurypterids are a very tricky group to study, since they were arthropods (joint-legged animals) that had external skeletons made up of many different components. In the specimens we are considering, the components have come apart in different ways and/or been squashed at different angles as they were buried in mud and fossilized. As a result, the patterns they make are extremely complex and difficult to decipher. One specimen may look like a jumble of legs and segments, while another may have the body twisted so that, at first, it may be difficult to tell where the head is.

One of the eurypterids in our collection, from the William Lake site.

A specimen may, indeed, look like a jumble of legs and segments!

Dave Rudkin discussing some of the eurypterid photos, compiled on his computer.

We have many eurypterid specimens in our storage cabinets, so Dave and Michael are pulling out each one, examining it closely, consulting the notes that they made previously, and in many cases taking photographs to supplement the ones we already have on hand. Ed Dobrzanski and I are making sure that Dave and Michael have all the tools and space they need, and I periodically supply them with opinions, observations, data, and coffee and cookies.

It seems to be working well so far. Still miles to go before we see where we are with the project at the end of the day Friday, but I’m sure the research will be exciting and interesting, at the times when it isn’t exasperating and frustrating!