As a repository for over 2.8 million artifacts and specimens, the Manitoba Museum possesses a collection that is made up of pretty much everything and anything you can imagine! One of the more humble artifacts that you might not think of in the museum’s collection, and one that is of practical use in everyday lives, are books. I personally only thought of books as the stories or information that was contained within, until two years ago, when a particular book came across my workbench.

In the summer of 2018, a very excited Dr. Roland Sawatzky, Curator of History, came into the conservation lab with a very large and heavy book in his hands. It was a Brown’s Bible, that belonged to Reverend John Black. I won’t delve into the specifics of John Black but will mention that his story is tied to the early beginnings of the Red River Settlement around 1851.

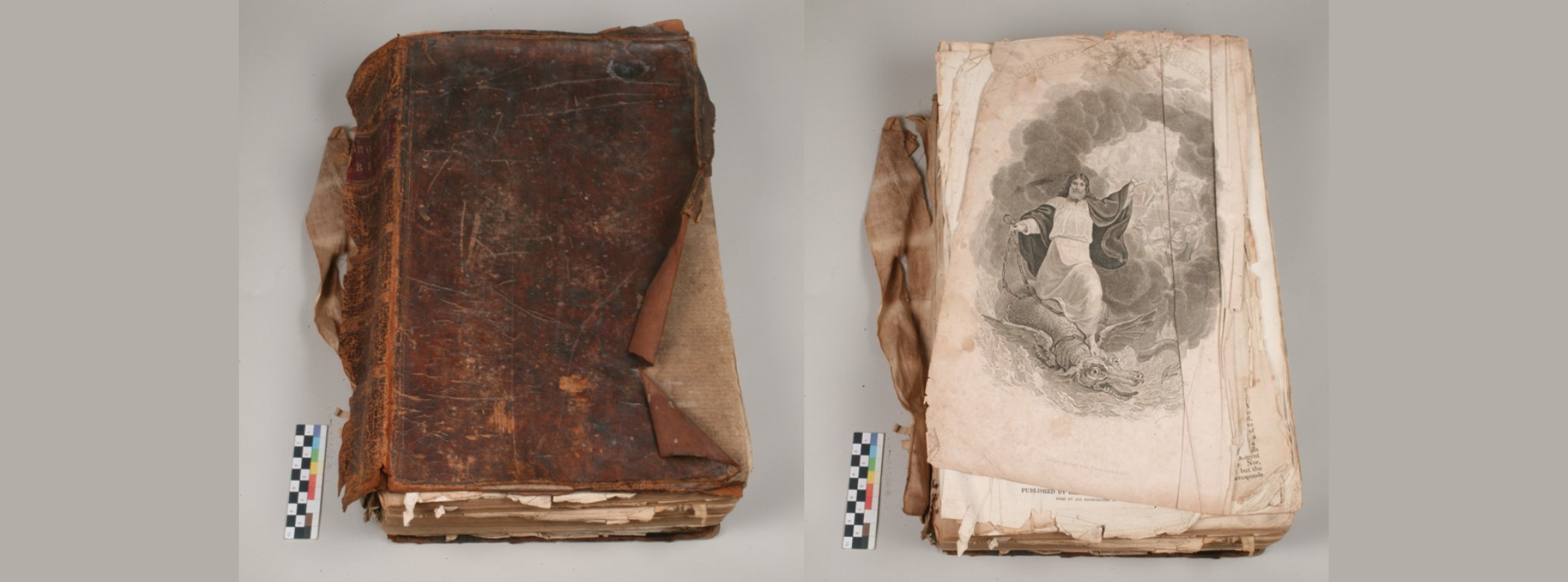

When Dr. Sawatzky brought the Bible into the conservation lab, it was in very poor condition. Perhaps a sign of its dedicated use and a symbol of how far it has travelled both in time and distance. The coverboards were falling off, the spine was torn and abraded, numerous sections of pages were loose as well as heavily soiled and damaged. Chosen to be displayed in the new Prairies Gallery, opening in the fall of 2020, it would need a lot of love and care to ensure its safe display.

In January of 2019, I began to dissect the Bible, knowing the repair would take a few months. Books are interesting objects to work on because they are all created differently depending on their age. Binding structures, sewing methods, the type of glue used, printing methods, and machinery all play an important role in telling the history of these otherwise mute objects. The Brown’s Bible is an excellent example of this, in telling a larger narrative based on how it was made rather than the person who owned it or the written text.

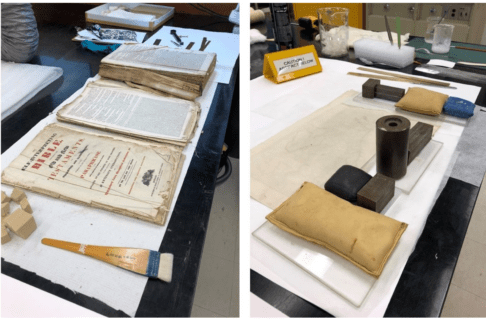

The repair began with taking a large portion of the Bible apart. Loose pages were removed, the front and back cover boards were taken off, including cutting the spine. This was a frightening feeling for someone who is used to repairing damage, not creating more! From there, about one hundred of the loose pages were mechanically cleaned, washed, flattened, dried, and repaired. Did I say washed? Yes, that is correct. A small “secret” in conservation is that paper can be washed, but inks are first checked for solubility and we make sure the paper fibers can handle the process.

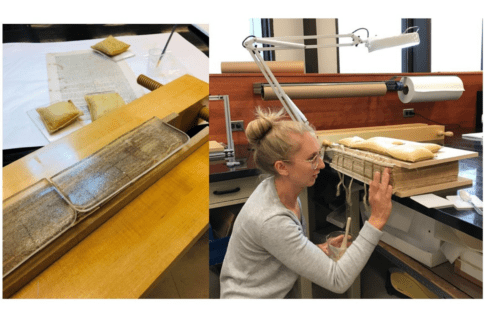

While the pages were drying, the front and back coverboards were worked on. These were cleaned, humidified and the leather re-adhered into the original position. The spine was the trickiest part of the whole piece, in that the original cloth used to hold the coverboards to the text block was too weak and a new cast had to be made for the spine to go on. Small details such as the paper raised bands on the spine are telling signs of the type of intricate details the original bookbinder put into his craft.

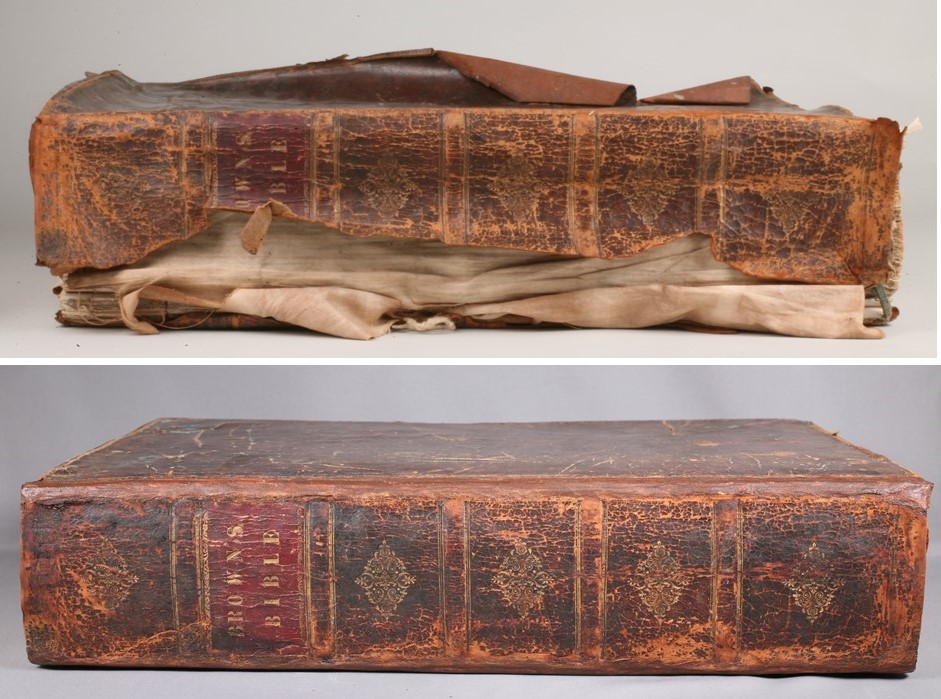

After about 8 months of work, the finale to this treatment was nearing. The old adhesive on the spine was removed, the cleaned pages were re-sewn and coverboards were ready to be attached. Looking at this book now, as it hopefully resembles what it once did over two-hundred years ago, I am excited to see it showcased in the new gallery for others to learn not only who owned it, but how it was made and the story behind its repair.

Spine of the Bible before and after conservation treatment.

Image: © Manitoba Museum, H9-4-973