Posted on: Tuesday February 11, 2014

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

A couple of weeks ago, I gave a presentation at McNally Robinson in Winnipeg, as part of our Museum lecture course Into the Vault. I was planning to talk about the ancient island shoreline deposits we have been studying in the Churchill area, and as I thought about history and pre-history, I was reminded of an observation I had made during an earlier trip to southwestern Manitoba. In most parts of a relatively flat landscape, the ground surface is the result of processes in the present day and the recent past; it is only where some of that surface is peeled away that we can really see evidence of a deeper past.

Downtown Winnipeg, as it has looked so often this winter.

The endless horizon of a flat landscape in western Manitoba.

Our modern landscape is different from all past landscapes.

On the surface, we can see evidence of the historic past: an abandoned farmhouse at Brockinton, Manitoba.

Where the earth is split open, along riverbanks and shorelines, and at roadcuts and quarries, we can see its older layers. While the surface usually represents the present, recent past, and relatively recent prehistory, the layers below that surface may be extremely old. Southwestern Manitoba and the Hudson Bay Lowland are both in the part of North America known geologically as the Platform, which has been free for a very long time from disruptive forces such as earthquakes and volcanoes. As a result, the layers are relatively orderly; the sediment was laid down almost horizontally, layer upon layer. Slicing through them vertically looks quite similar to slicing an onion with a knife.*

As we dig down into the upper surface of the land, below the historic remnants we can see evidence of prehistoric occupation of this region. Almost everyone is familiar with widespread artifacts such as arrowheads, but in some places in southern Manitoba we can see ancient burial mounds or traces of long-past hunting sites.

Elsewhere, the cuts in the Earth extend into older layers. Some of these layers are still made of sediment that has not been turned to rock, but they date from the late part of the Ice Age, before people are known to have lived in this part of the world.

Calf Mountain, near Morden, is an ancient burial mound.

Kevin Brownlee examines bison bones at a hunting site dating from about 1200 years ago.

Near St. Lazare, Kevin looks at a cut bank is composed of till (sediment) deposited thousands of years ago by a glacier.

If the cut is deep enough, or if a high part of the bedrock reaches up to near the surface, we may see layers that date from long before the Ice Age. For example, along the Manitoba Escarpment there are many places where strata of Cretaceous age can be seen. These beds, dating from the later part of the age of the dinosaurs (roughly 100 million to 66 million years ago), are composed of shale and related rocks made of sediment deposited in the Western Interior Seaway.

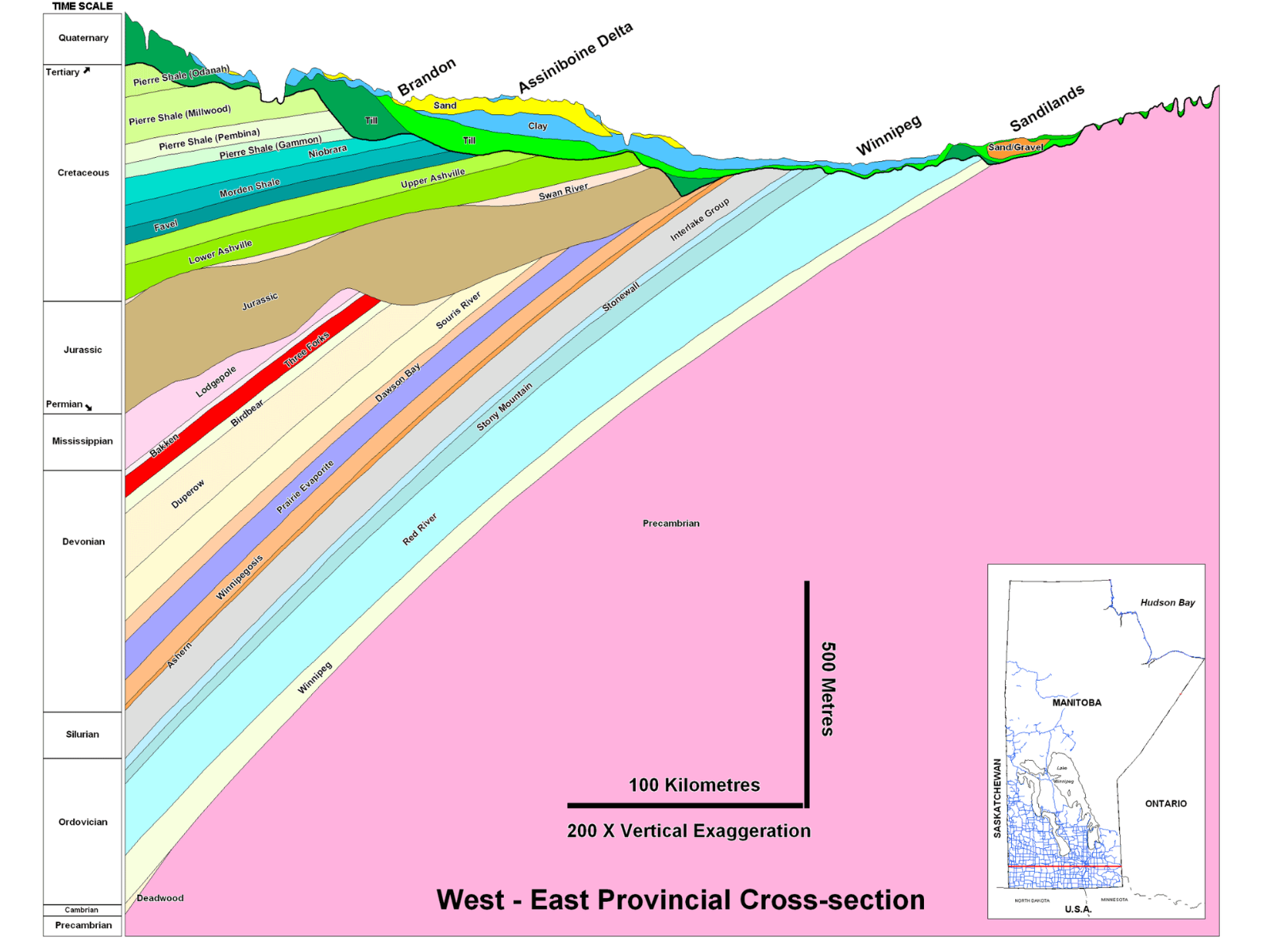

If you were to drill a vertical hole into the Earth anywhere in southwestern Manitoba, your drillbit would eventually pass down through the Cretaceous layers into successively older beds of Jurassic, Mississippian, Devonian, Silurian, and Ordovician age (see diagram below). Units of these ages are always in the same order, from youngest at the top to oldest at the bottom, thanks to the simple and straightforward law of superposition and principle of original horizontality. Basically, sediment layers deposited by water or wind tend to be close to horizontal due to gravity, and each layer is laid down on top of the older layers that are already present in an area.

Image: In the Wawanesa gorge of southwest Manitoba, the upper yellowish sediments are glacial and postglacial, while the lower grey ones are from the Late Cretaceous Period.

The geological time gaps in the Manitoba record (such as between the Mississippian and Jurassic rocks, where we might have expected deposits from the Pennsylvanian, Permian, and Triassic periods) simply represent intervals in which sediment was not being deposited in this region, and was perhaps being eroded. Most of our sedimentary rocks were deposited under seawater; the intervals of deposition occurred at times when the sea invaded the middle of the continent, and the gaps in deposition represent times when the sea left this region. We are in the latter sort of situation nowadays, though of course sediment IS still being deposited in one part of the middle of North America: in Hudson Bay.

The layers in the diagram below look to be strongly tilted, but this is because the diagram has a 200x exaggeration of the vertical scale, relative to the horizontal. In reality, they are tilted just a few degrees. The tilt is related to their having been deposited on a seafloor that sloped gently toward the centre of the ancient sedimentary basin, which was located to the southwest.

A west to east geological cross-section through southern Manitoba shows how the older strata are located below younger ones (vertical scale greatly exaggerated). (Image from the Manitoba Geological Survey).

Limestone beds in the Fisher Branch area, north of Winnipeg, were deposited during the early part of the Silurian Period, about 440 million years ago.

This slight tilt is, however, very important when we consider where we might find particular layers on the surface. Geologists often talk about the rocks of the Platform as having “layer cake stratigraphy.” Like the onion, the layer cake is a useful metaphor. If we imagine a cake plate being tilted, and then the cake being cut parallel to the tabletop, it is obvious that the lower layers of the cake would be visible from above as you move away from the direction of tilting.

Similarly, in southern Manitoba we see older layers meeting the ground surface as we move eastward, away from the centre of the sedimentary basin. Although there is Cretaceous bedrock at the surface along the Manitoba Escarpment, the sedimentary rocks in the Winnipeg area are far older. North of Winnipeg we can visit sites that straddle the boundary between the Ordovician and Silurian periods, with Silurian beds about 440 million years old near Fisher Branch, and Ordovician beds 445-450 million years old at Stony Mountain and Stonewall.

The oldest Ordovician sedimentary beds in Manitoba, belonging to the Winnipeg Formation, can be observed toward the eastern side of Lake Winnipeg at places like Manigotagan and Black Island. Just east of these places, however, we reach the bottom of the layer cake. The “cake plate”, if you will, is composed of the very hard, very old rocks of the Precambrian Shield (aka Canadian Shield).

Image: Sandstones of the Ordovician Winnipeg Formation at Black Island, Manitoba, are about 454-458 million years old.

The Shield rocks are geologically complex, having been formed as mountains were growing, volcanoes erupting, and continents crashing together in this region about 1.8-3.5 billion years ago. Since they were formed by such active processes, they are often folded, faulted, and overturned; as a result we can no longer apply our simple onion/cake metaphors once we reach those rocks. But those comparisons work wonderfully in any of Manitoba’s younger strata!

* The growth of onions is apparently quite different from this age-layering of sediment on the Platform, but it is still a handy visual metaphor.