Posted on: Thursday November 13, 2014

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

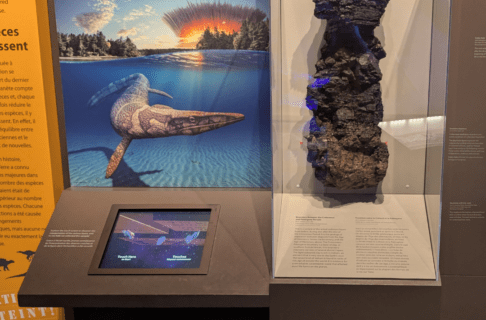

The Old Plesiosaur and the Sea Exhibit, Open November 14, 2014 – April 6, 2015

Tomorrow morning we will be opening our new Discovery Room exhibit, The Old Plesiosaur and the Sea. Some Discovery Room exhibits show exciting or previously unseen objects from the Museum’s collections, while others feature collaborations with the community. This exhibit will do both: some of the beautiful specimens have been donated over the past few years by two remarkable fossil collectors, but many of the other specimens are being loaned by those collectors, just for this exhibit.

The collectors, Wayne Buckley and Kevin Conlin, spend much of their spare time collecting and preparing fossils from Cretaceous rocks in the Manitoba escarpment. These fossils include large marine reptiles, beautiful fishes, and many other forms of sea life. The exhibit is intended to share with the public some of the fossils Wayne and Kevin have collected, along with the story of how and why they have carried out this difficult and complicated work.

The exhibit itself is partly tied to a donation to the Museum. This spring, Wayne Buckley very generously donated a plesiosaur, the skeleton of a huge swimming reptile that he had collected, prepared, and studied over a period of several years (hence the name of this exhibit). We are planning a major new gallery exhibit that will feature this fossil, but we wanted to share it with the Museum’s visitors as soon as possible, and this temporary exhibit seemed like a wonderful opportunity to also display some of Wayne and Kevin’s other fossils.

The photos below simply show parts of the exhibit, and some of the behind-the-scenes work that was required to put the specimens there. I will try to follow up in a week or so with some of the very interesting story of Wayne and Kevin’s fossil collecting.

After we brought the plesiosaur to the Museum, we worked on it in one of the back rooms. Here, we are placing the skull onto a cart so that it can be moved to the exhibit. L-R: Ed Dobrzanski, Bert Valentin, Ellen Robinson, Carolyn Sirett, Stephanie Whitehouse, me, and Sean Workman. (Photo by Randy Mooi)

Carolyn Sirett and Ellen Robinson accompany the skull in the freight elevator. (Photo by Randy Mooi)

Will it fit into the case? Fortunately the skull is not quite as big as it looks from here (note the metal mount, devised by Bert and Carolyn). (Photo by Randy Mooi)

All together now! The skull is heavy and fragile, a tricky thing to move into a tight space. L-R: me, Stephanie Whitehouse, Bert Valentin, Sean Workman. (Photo by Randy Mooi)

Adjusting the skull on its mount.

The plesiosaur skull and neck vertebrae (V-3151).

A splendid example of the fishIchthyodectes, disarticulated (broken up) by currents or scavengers on the ancient seafloor. This fossil was donated to the Museum by Wayne Buckley. (V-3122)

Sharks are widespread in Manitoba’s Cretaceous rocks. Shark teeth are very hard and commonly fossilized. Shark skeletons are made of softer cartilage, so most parts of the skeletons are rarely preserved. As shown by the specimens here, however, vertebrae (backbones) and jaws are sometimes fossilized because those parts are hardened with calcium salts. The fossils in this case are on loan from Wayne Buckley.

Some of the fossils in the “Cretaceous Community” case: an example of plesiosaur ribs and gizzard stones (1), the snout of the bony-headed fish Thryptodus? (2), and a vertebra from an elasmosaur (long-necked plesiosaur) (3). These fossils are on loan from Kevin Conlin (1, 3) and Wayne Buckley (2).

One of my favourite fossil specimens is this Cretaceous seabird, loaned for the exhibit by Kevin Conlin. The bird is still partly enclosed in dense shale matrix; the X-ray below shows that most of the skeleton is actually present.

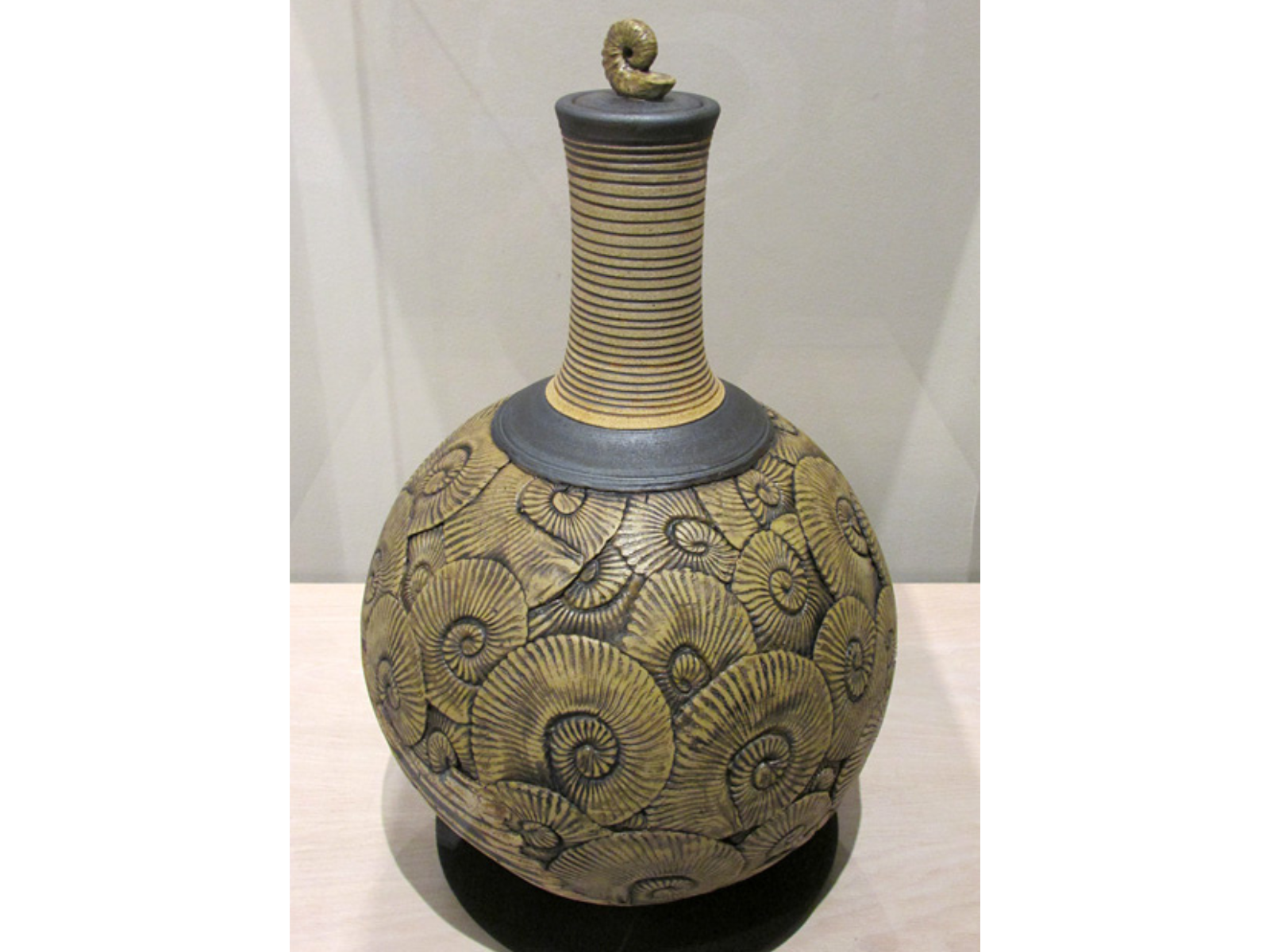

Kevin Conlin is a professional ceramic artist. This ammonoid urn was inspired by Cretaceous fossils and rocks.