Posted on: Friday August 23, 2013

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

2. Mongolian Basalt

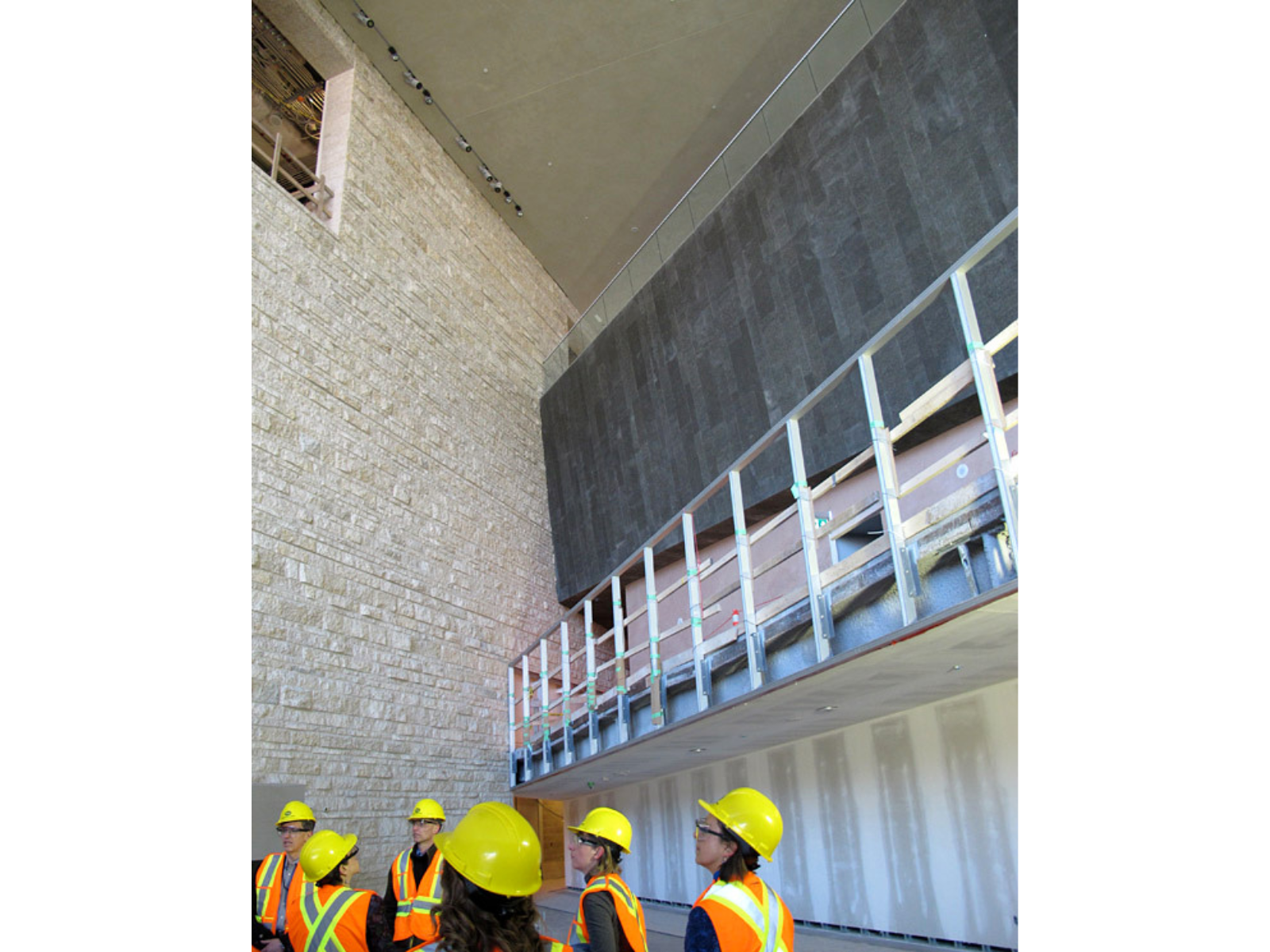

Slabs of dark igneous stone, apparently basalt or diabase, can be seen covering some walls in the lower parts of the museum, but for a geological appreciation of volcanic rock the visitors must wait until they have passed upward into the huge Garden of Contemplation. This is the finest place I know of for viewing columnar-jointed igneous rocks, between Thunder Bay and the Rockies!

Image: Walls of Tyndall Stone (left) and dark igneous stone in the lower part of the museum.

Columnar jointing is a term used to describe the polygonal columns seen in many volcanic rocks. These developed as a result of stresses, when lava cools from a molten form. Famous columnar basalts can be seen in places like the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland, and at many sites around the Bay of Fundy in eastern Canada (columnar-jointed bedrock in the Lake Nipigon area of Ontario has a similar appearance, though much of it may have actually formed from magma that was intruded between other rocks, rather than erupted onto the Earth’s surface).

Columnar-jointed igneous rock caps this hill in the Lake Nipigon area, Ontario.

Columnar-jointed basalt at Southwest Head, Grand Manan Island, New Brunswick.

The stone that I saw being installed in the Garden of Contemplation consists of 617 metric tonnes of Mongolian basalt. 617 metric tonnes Ogunad, Mongolia – architect Antoine Predock had a particular vision about materials – large surfaces, not so much as features – outcome of what could be done only with computer-assisted design – based on hundreds of piles and caissons, presumably down to bedrock that underlies the river and lake deposits that make Winnipeg ground so unstable – ramps cross over a “canyon” of dark concrete – total of 18,000 square metres of Tyndall Stone – much of it exposed as rough surfaces – these are stylolites (pressure solution features), which are the natural planes of weakness within the bedrock – I assume that the alabaster is slabbed bed-parallel to give it this appearance – glass, concrete, and steel are also geologically-derived materials, of course references Geomorphology 81 (2006) 155–165 Did the Ebro basin connect to the Mediterranean before the Messinian salinity crisis? Julien Babault a,⁎, Nicolas Loget b, Jean Van Den Driessche a, Sébastien Castelltort c, Stéphane Bonnet a, Philippe Davy