Posted on: Monday March 30, 2020

Throughout its history, the Hudson’s Bay Company had a tradition of recruiting young men from Scotland to serve as clerks, traders, and labourers in its North American posts, offering both adventure and security of employment. Housing and basic needs were covered, but luxuries like sugar, tea, tobacco, and brandy were bought from the post by the men themselves and deducted from their wages. Commerce didn’t stop at the four walls of the post; these men frequently acquired handmade objects from Indigenous women in the communities they lived in, both for their personal use and to send home as gifts for loved ones. Since arriving at the Manitoba Museum, the Hudson’s Bay Company Museum Collection has received donations of these objects from former HBC employees and their descendants, highlighting the skilled work of Indigenous women across Canada. By and large, unfortunately, we lack information on these artisans and turn to our collection for answers – using other objects with similar breading or embroidery styles and techniques that have more robust records, we can often identify which cultures or communities may have produced specific objects.

In the summer of 2018, we received a package from Scotland, full of objects, photographs, and documents that told the story of an HBC employee in northern Manitoba in the 1920s. By the 1920s, HBC was more rigorous in their recruiting process. As opposed to “just showing up” like days of yore, men needed to present personal and professional references and pass a physical examination before being offered a contract. Our new acquisition had all these documents and more…but who was this intrepid young Scot that sailed across the Atlantic to the unknown?

Born May 25, 1902 in Aberdeen, Scotland, George Fowlie lost his father at a young age. After finishing school at Robert Gordon’s College in 1917, he worked at North of Scotland and Town & Country Bank. In 1923, when he entered into service on a five-year contract with the Hudson’s Bay Company as an apprentice clerk at York Factory in HBC’s Nelson River District. We have no concrete evidence as to why Fowlie decided to join HBC or leave the bank; his references were glowing- but his daughter suggested that he was single and looking for adventure. Fowlie made the most of his time at York Factory. He traded his desk job for a cariole and dog whip as Fowlie worked with dog sled teams, creating strong bonds with his canine colleagues. He also formed a tight knit community with his fellow Scotsmen, enjoying music played on the gramophone and partaking in the culture of York Factory, which include socializing and working with the Indigenous community in the area.

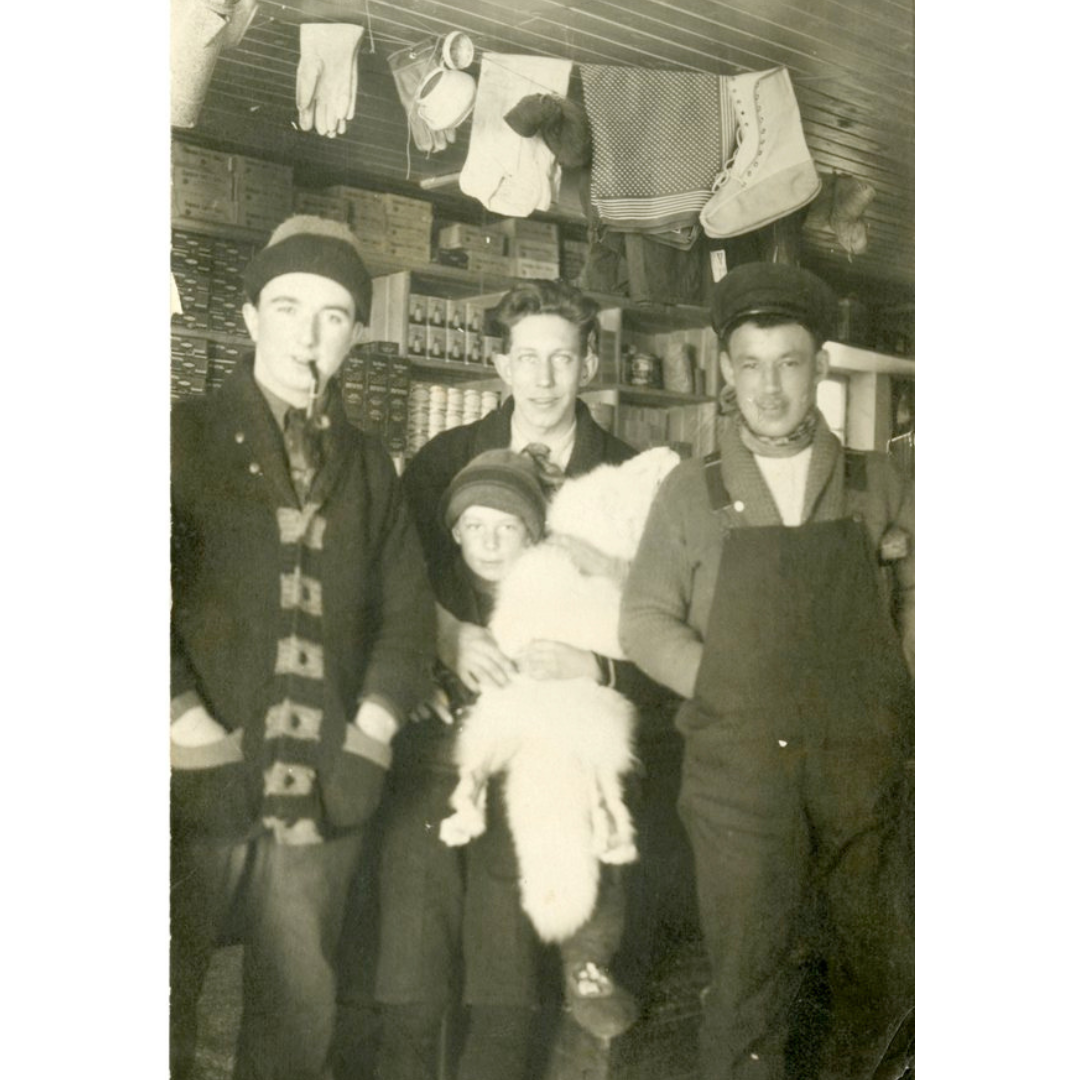

George Fowlie in York Factory. Image: © Manitoba Museum, HBC 018-84

Fowlie documented his experiences and the people at York Factory through photography, including his work mates, his dogs, himself playing with local children and sharing a laugh with young women in front of the Anglican Church.

These candid images of HBC employees, local Indigenous peoples and the buildings and landscape also give us a rare glimpse at HBC’s working class and a real idea of what life was like for the community at York Factory.

George Fowlie and friends with his canine companions, York Factory. Image: © Manitoba Museum, HBC 018-76

A gathering outside the Anglican church in York Factory. Image: © Manitoba Museum, HBC 018-107

George Folwie and colleagues, York Factory. Image: © Manitoba Museum, HBC 018-76

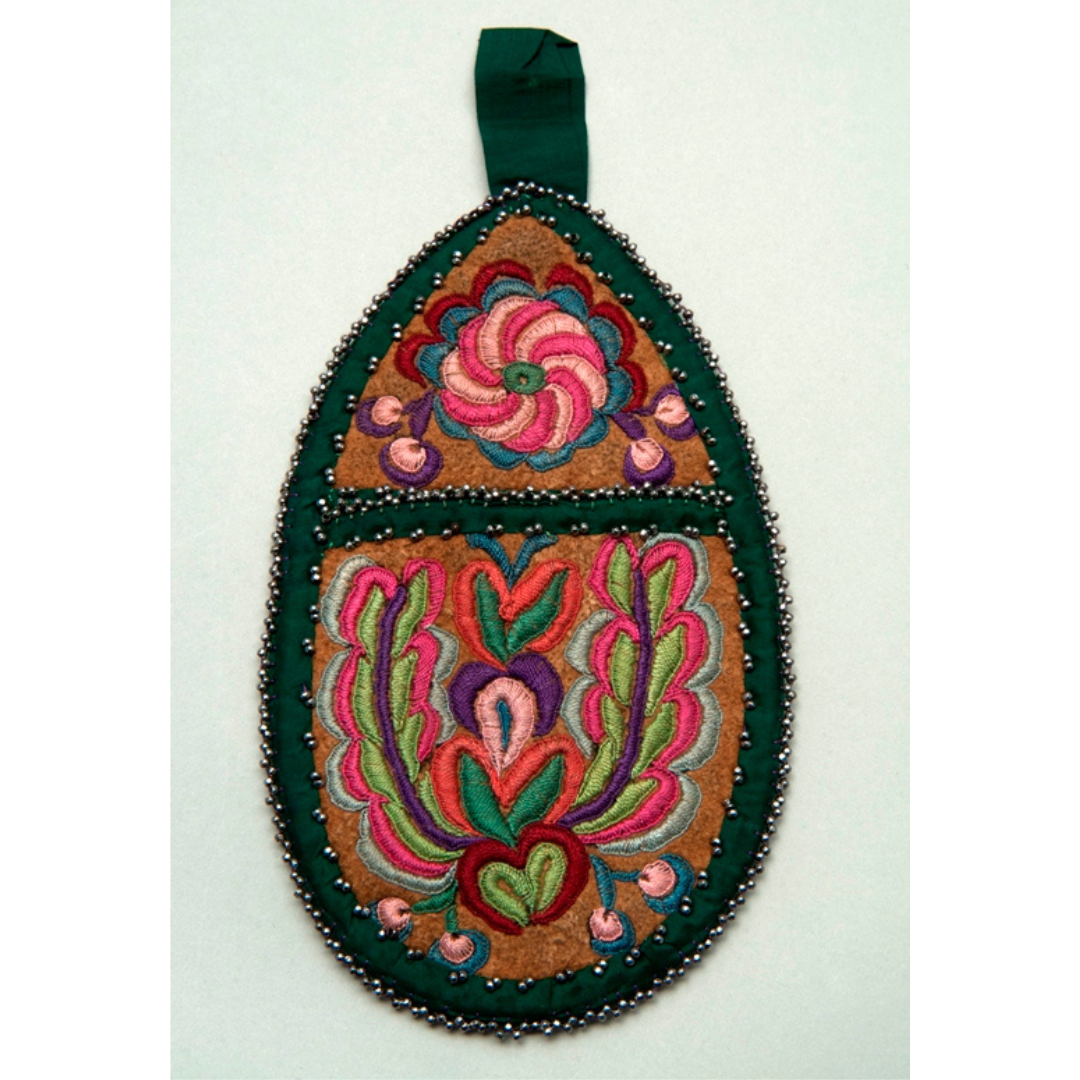

Fowlie also carefully preserved the beloved handmade objects he likely acquired from Cree or Métis women during his tenure at the post –some that he used in his everyday life such as moccasins and gauntlet gloves and some that he sent back to Scotland as gifts for his mother, a number of wall pockets and a beaded belt.

Beaded belt. Image: © Manitoba Museum, HBC 018-28

Embroidered wall pocket. Image: © Manitoba Museum, HBC 018-33

Gauntlet gloves. Image: © Manitoba Museum, HBC 018-25

Upon leaving the HBC, Fowlie returned to Scotland and worked as a chauffeur until WWII. Following his service in WWII as clerk in the Royal Air Force, he married Madge Briggs and had daughter Marjorie in 1947. When Fowlie passed away in 1985, his HBC collection was passed down to Marjorie, who appreciated the historical significance of her father’s objects. She decided to donate the collection to the Manitoba Museum, but not before making a quick stop on Antiques Roadshow to showcase these beautiful pieces, and allowing them to be researched and exhibited by the University of Aberdeen. Thanks to George Fowlie and his family’s care, these objects have officially made their Manitoba homecoming.