Posted on: Monday April 10, 2017

When the weather turns cold many of us pull out handcrafted quilts and afghans. The comfort they bring often goes beyond the mere physical and can make us feel as if the people that created them are enveloping us in a warm and loving hug. Recently, a very special quilt was donated to the Manitoba Museum. One of thousands sent overseas by the Canadian Red Cross during the Second World War to provide warmth and comfort, it has now returned home to Manitoba nearly 75 years later.

Red Cross Quilt, H9-38-563. © The Manitoba Museum

Betty Craddock with son Anthony. © Anthony Craddock

The story of the quilt begins in Steep Rock, Manitoba where local women would have been part of a network of participants in the Red Cross “Women’s War Work” sewing and knitting program. It was likely sorted and packed at a Red Cross facility before being shipped overseas and on to the Dudley Road Hospital in Birmingham. There, a Matron passed the quilt on to Cynthia (Betty) Craddock sometime towards the end of the war. Betty worked as a lathe operator making tank parts in a factory in Coventry. Her husband Joe had completed apprenticeship as a painter and decorator and then was called up for the army in 1940. He worked as a cook for the Army Intelligence Corp, serving in England and Wales. Joe reached the continent just after D-Day and was among the first troops in Belgium. They had married in 1943 and were together for over 70 years. Their only son Anthony was born in 1945.

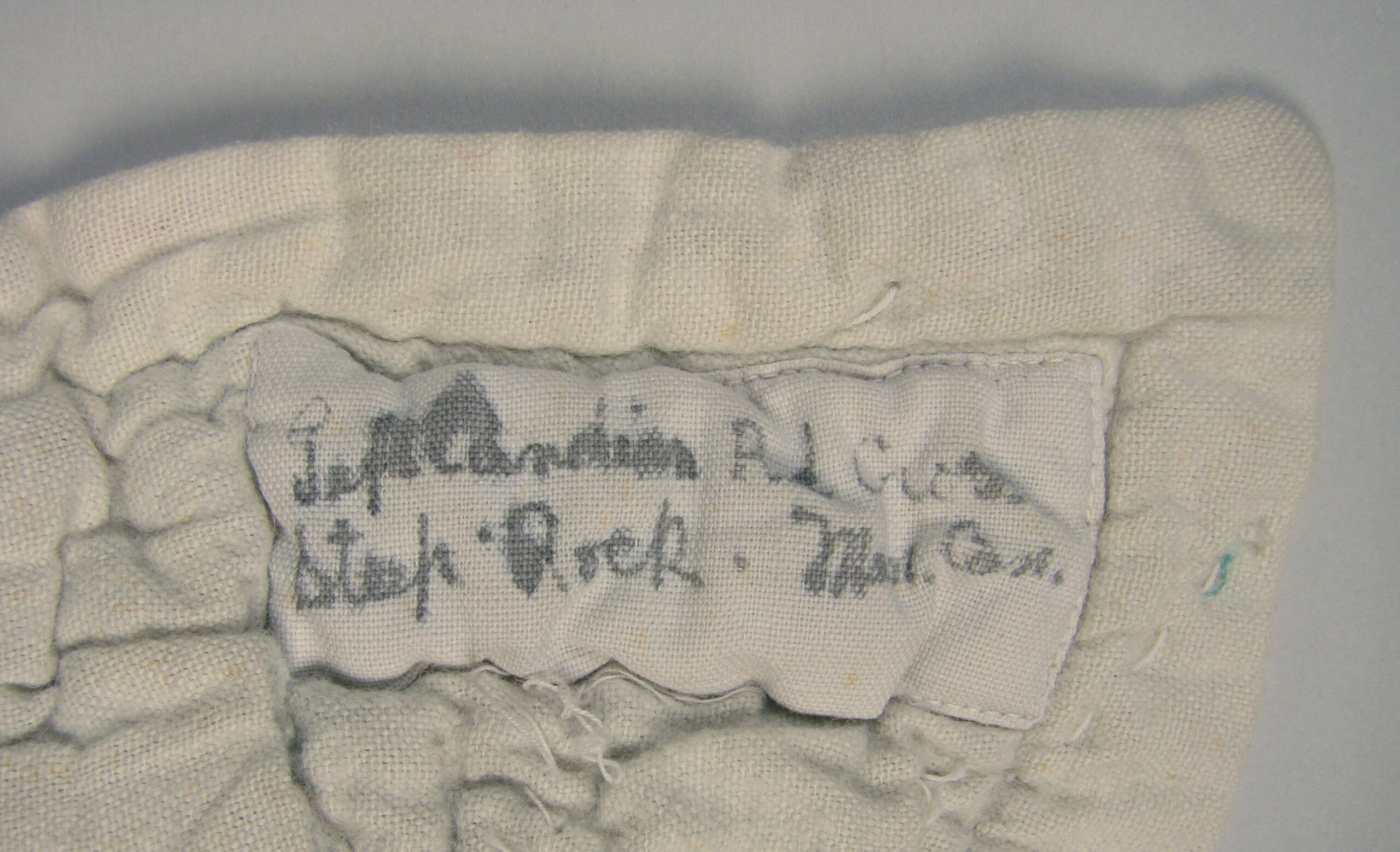

Following the war, the family moved to Kenilworth and the quilt went along with them. Britain was recovering from the war and rationing was still in place. Joe was working to start his own business. Anthony’s earliest memories are “of this quilt being on my bed and keeping me warm when times were hard.” He recalls that, “with no central heating, frost would often appear on the inside of the window.” The young Anthony was amazed by the colours and patterns and remembers reading the message on a tag on one corner of the quilt, “Gift Canadian Red Cross, Steep Rock Man. Can.”

Image: Close-up of label on quilt. © The Manitoba Museum

The Canadian Red Cross Society was founded in 1896. The purpose of the Society, as set out in its 1909 Act of Incorporation, was “to furnish volunteer aid to the sick and wounded of armies in time of war”. Following WWI, the Red Cross expanded its role into public health, especially in remote or newly settled areas of Canada. The two mandates merged in WWII as the Red Cross worked with military personnel and civilian victims of the war. On the home front, countless volunteers worked to high standards creating supplementary hospital and relief supplies.

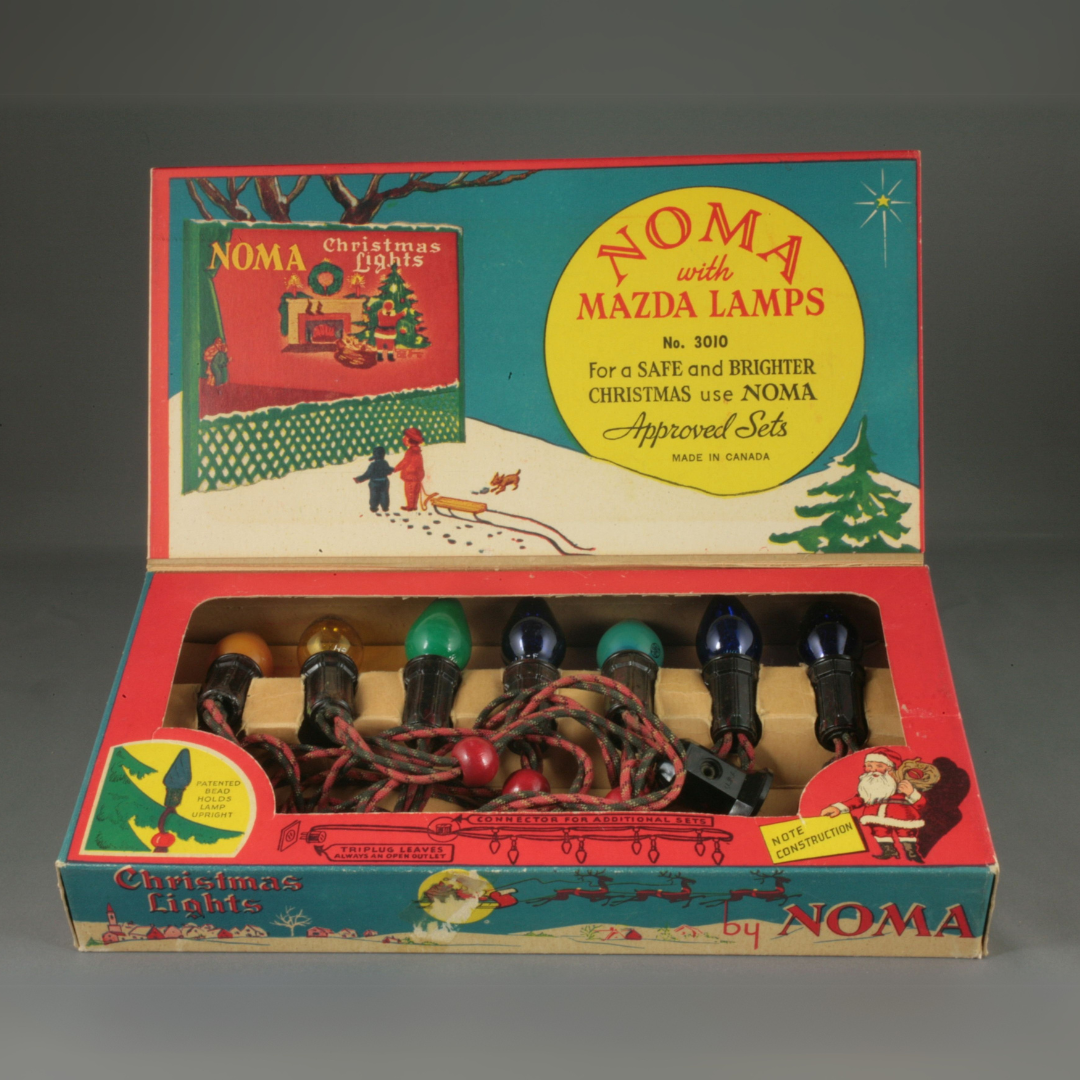

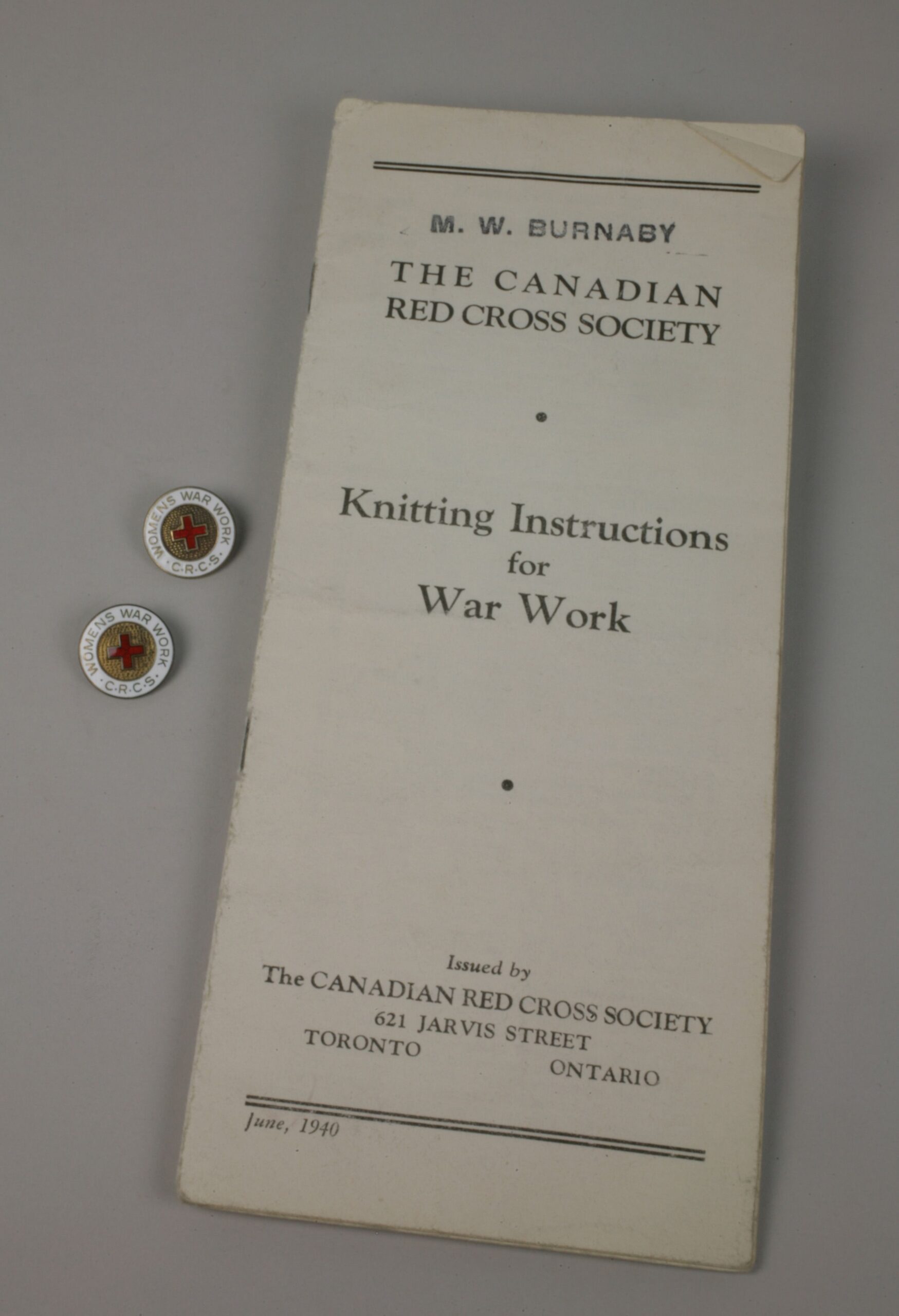

The Canadian Red Cross Society distributed patterns and lapel pins to volunteers in the “Women’s War Work” program.

Lapel pins, H9-22-407 and H9-31-994, Knitting Pattern, H9-29-545. © Manitoba Museum

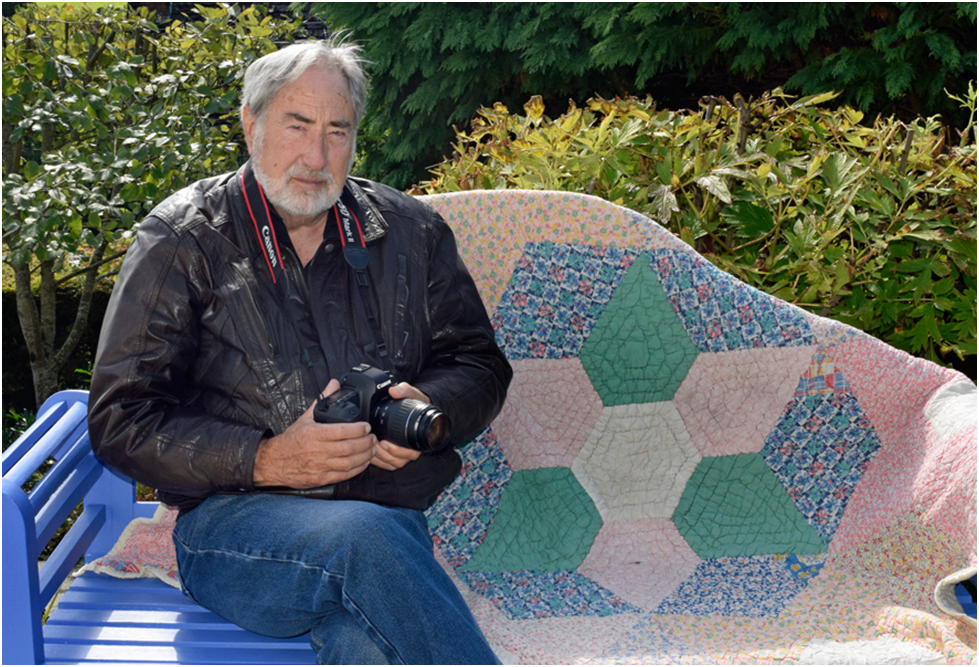

Anthony Craddock has been a professional photographer since 1965 and is now a director of Images Etc Ltd”. Anthony Craddock with quilt, 2016. © Anthony Craddock

Now that the quilt has been received into the museum’s collection, Roland Sawatzky, Curator of History is looking forward to sharing it with the community and perhaps learning more about the “hands-on” humanitarians who sewed it. As the women of Steep Rock gathered to create this quilt, I’m sure they would not have imagined that it would be treasured by the receiving family into the next century.

Sources:

120 Years of the Canadian Red Cross at www.redcross.ca/history/home

Biographical and historical notes provided by Anthony Craddock