September brings the official beginning of fall in the northern hemisphere, the beginning of school for most students, and an end to summer vacation for many. It’s also one of the best months to stargaze, with cooler temperatures and earlier sunsets bringing the dark that much sooner.

The Solar System for September 2025

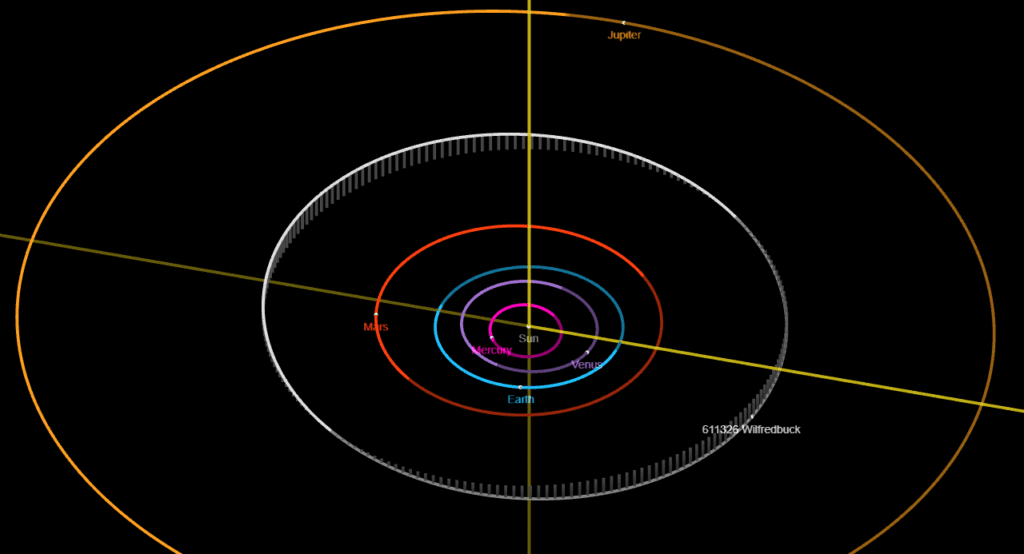

Mercury is not visible this month as it passes around the far side of the Sun.

Venus rises about 4 a.m. in early September, but dips lower into the Sun’s glare as the month goes on. On the morning of the 19th the thin crescent moon passes very close, a striking pre-dawn sight worth getting up for. By month’s end it is still low in the east before sunrise.

Mars is too close to the Sun (as seen from Earth) to be visible this month.

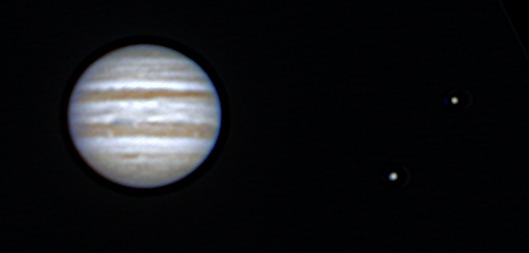

Jupiter rises about 2 a.m. in the east on September 1st, shining to the right of the twin stars Castor and Pollux. Jupiter is just beginning its season of visibility for 2025, and it will grow brighter and rise earlier as it approaches its opposition in January 2026.

Saturn rises about 9 p.m. in the east at the beginning of September. It is at opposition on September 21, which means it is opposite the Sun in our sky and thus visible all night. Saturn’s rings are only tilted by a couple of degrees relative to our line of sight, which means they appear very thin and edge-on. The situation gets worse throughout the year, as the rings will nearly disappear from our point of view. They’re still there, but they are so thin that it’s like looking at the edge of a piece of paper. On the plus side, for those with large telescopes, we will be able to see some of Saturn’s moons cast their shadow on the planet as they orbit. Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, casts its shadow on the planet on the nights of September 3-4th and 19-20th this month. The waxing gibbous Moon is nearby on the morning of August 12 (see below).

Uranus is in the morning sky a few degrees below the famous Pleaides star cluster (also known as the Seven Sisters). It is too faint to easily see without binoculars, and even a telescope shows it as a faint dot that looks just like the other faint stars. A detailed star-charting app like Stellarium is required to track it down.

Neptune is in the same binocular field of view as Saturn for the entire month, but since it is even farther than Uranus it is invisible without optical aid. Neptune requires good binoculars or a small telescope to even spot, and a large telescope to make it out as anything more than a faint dot. Again, a detailed star chart like those produced by Stellarium is required to tell which tiny “dot” is Neptune.

Of the five known dwarf planets, only (1) Ceres is close enough to be seen in binoculars or a small telescope. In September, Ceres is approaching its brightest for the year on October 2, below and to the left of Saturn and Neptune. You should be able to spot it in binoculars as a faint “star” that slowly changes its position each night.

Sky Calendar for August 2025

All times are given in the local time for Manitoba: Central Daylight Time (UTC-5). However, most of these events are visible across Canada at the same local time without adjusting for time zones.

If there’s a little box to the left of the date, you can click on it to see a star map of that event! All images are created using Stellarium, the free planetarium software.

Wednesday, September 3, 2025: Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, casts its shadow on the planet’s cloudtops between 00:12 am CDT and 4:11 am CDT.

Sunday, September 7, 2025: The Full Moon rises to the right of Saturn this evening, and slowly approaches the ringed planet throughout the night. There is a lunar eclipse during this full moon, but the eclipse is not visible from North America.

Monday, September 8, 2025: The just-past full Moon rises to the left of Saturn this evening.

Saturday, September 13, 2025: Mercury reaches superior conjunction – passing around the far side of the Sun from our point of view on Earth.

Sunday, September 14, 2025: Last Quarter Moon

Tuesday, September 16, 2025 (morning sky): The crescent Moon is near Jupiter and the bright stars Castor and Pollux this morning.

Sunday, September 21, 2025: New Moon. Also today, the ringed planet Saturn reaches opposition, rising at sunset and being visible all night long.

Monday, September 29, 2025: First Quarter Moon

Summer Meteor Showers

Outside of the regular events listed above, there are other things we see in the sky that can’t always be predicted in advance.

Aurora borealis, the northern lights, are becoming a more common sight again as the Sun goes through the maximum of its 11-year cycle of activity. Particles from the Sun interact with the Earth’s magnetic field and the high upper atmosphere to create glowing curtains of light around the north (and south) magnetic poles of the planet. Manitoba is well-positioned relative to the north magnetic pole to see these displays often, but they still can’t be forecast very far in advance. A site like Space Weather can provide updates on solar activity and aurora forecasts for the next 48 hours. The best way to see the aurora is to spend a lot of time out under the stars, so that you are there when they occur.,

Random meteors (also known as falling or shooting stars) occur every clear night at the rate of about 5-10 per hour. Most people don’t see them because of light pollution from cities, or because they don’t watch the sky uninterrupted for an hour straight. They happen so quickly that a single glance down at your phone or exposure to light can make you miss one.

Satellites are becoming extremely common sights in the hours after sunset and before dawn. Appearing as a moving star that takes a few minutes to cross the sky, they appear seemingly out of nowhere. These range from the International Space Station and Chinese space station Tianhe, which have people living on them full-time, to remote sensing and spy satellites, to burnt-out rocket parts and dead satellites. These can be predicted in advance (or identified after the fact) using a site like Heavens Above by selecting your location.

![A simulated view of the "parade of planets" on March 2, 2025. [Image: Stellarium]](https://manitobamuseum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/stellarium-001-e1740764429838.png)