Posted on: Tuesday June 22, 2021

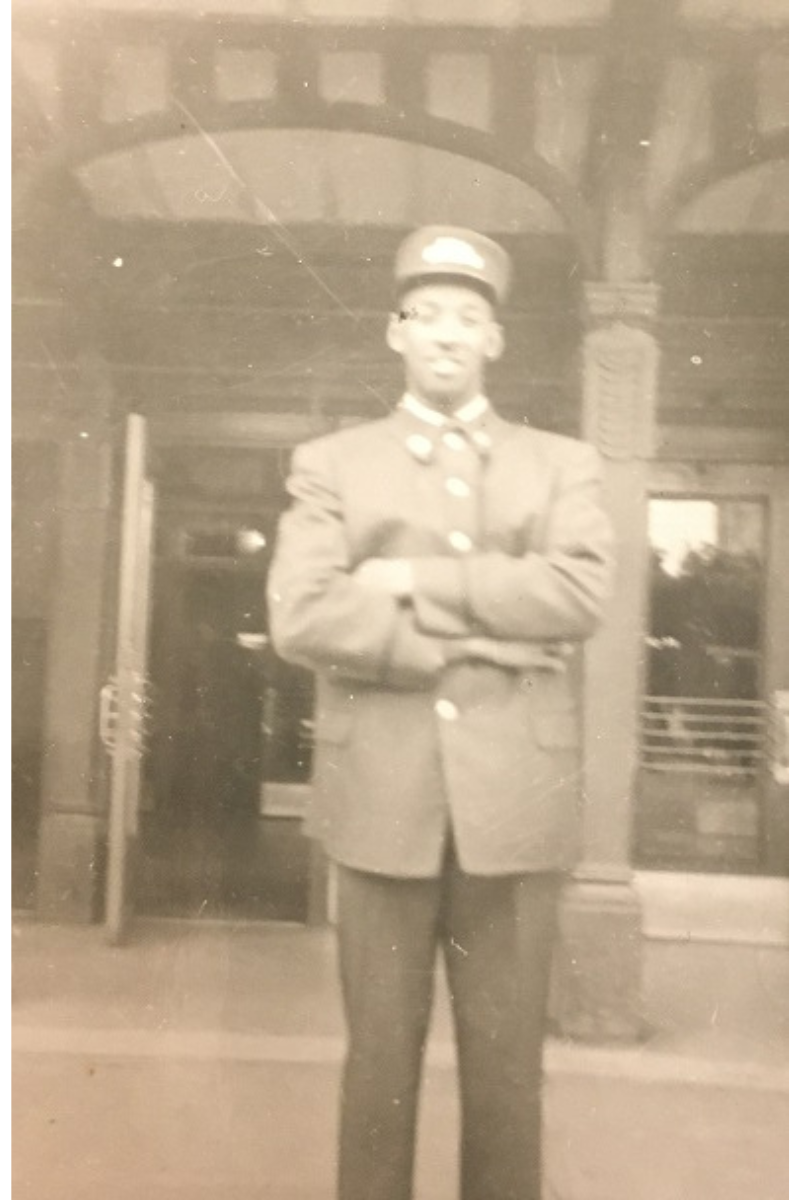

In recognition and celebration of National Indigenous History Month, we’re featuring an artifact from Private David Thomas, a Peguis First Nation soldier who died in the First World War. An exhibit featuring his story and a handkerchief he had sent to his sister from Europe was on display in November 2020. Unfortunately we closed to the public that week because of a COVID-19 province wide lockdown, and no one was able to see the exhibit! We’re putting it up again in November, 2021, and then it will become part of the Parklands Gallery “Impact of War” permanent exhibit.

David Thomas was only 18 years old when he left his home at Peguis Reserve to fight in the Great War in Europe. He joined the 108th Battalion (Selkirk) in 1916, which was soon shipped out to England. A year later he was killed in the Battle of Passchendaele, in Belgium. Private Thomas died on October 26, 1917, the first day of the assault, possibly a victim of a poison gas attack. The 27th Battalion (City of Winnipeg), was finally able to capture the village of Passchendaele on November 6. Over 4,000 Canadians died and almost 12,000 were injured in two weeks of horrific fighting.

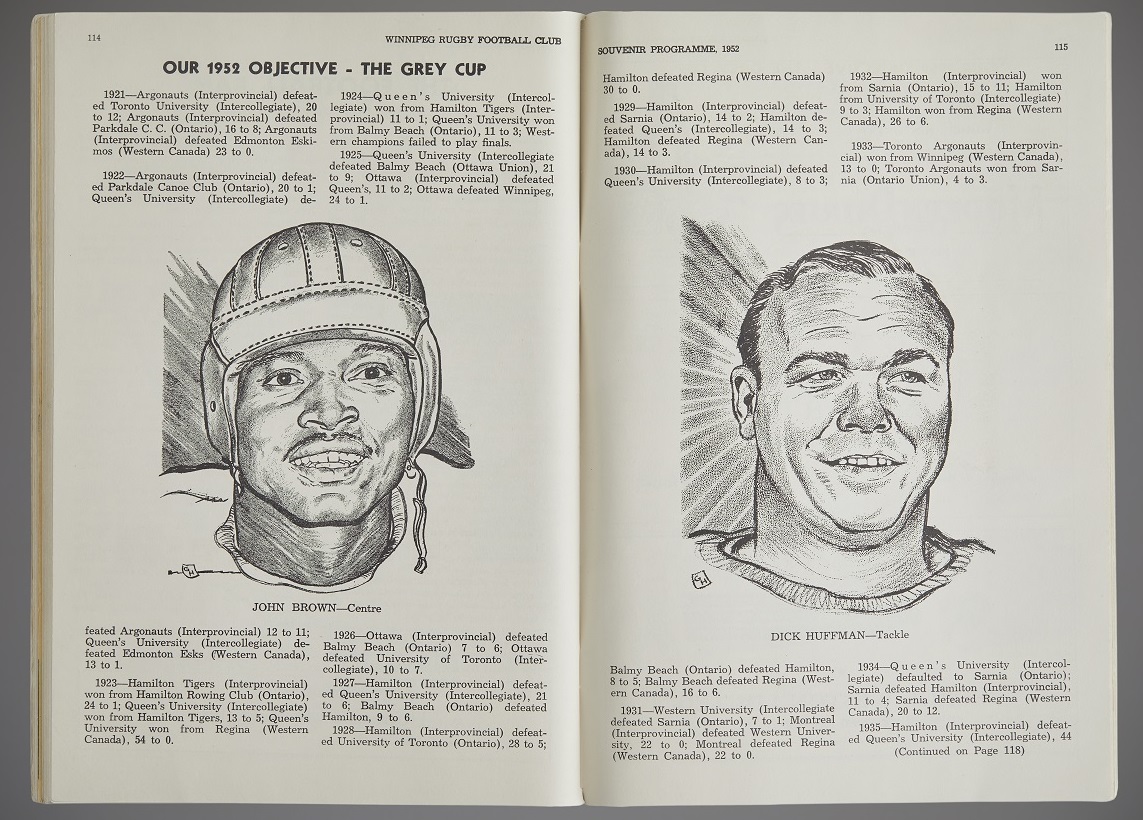

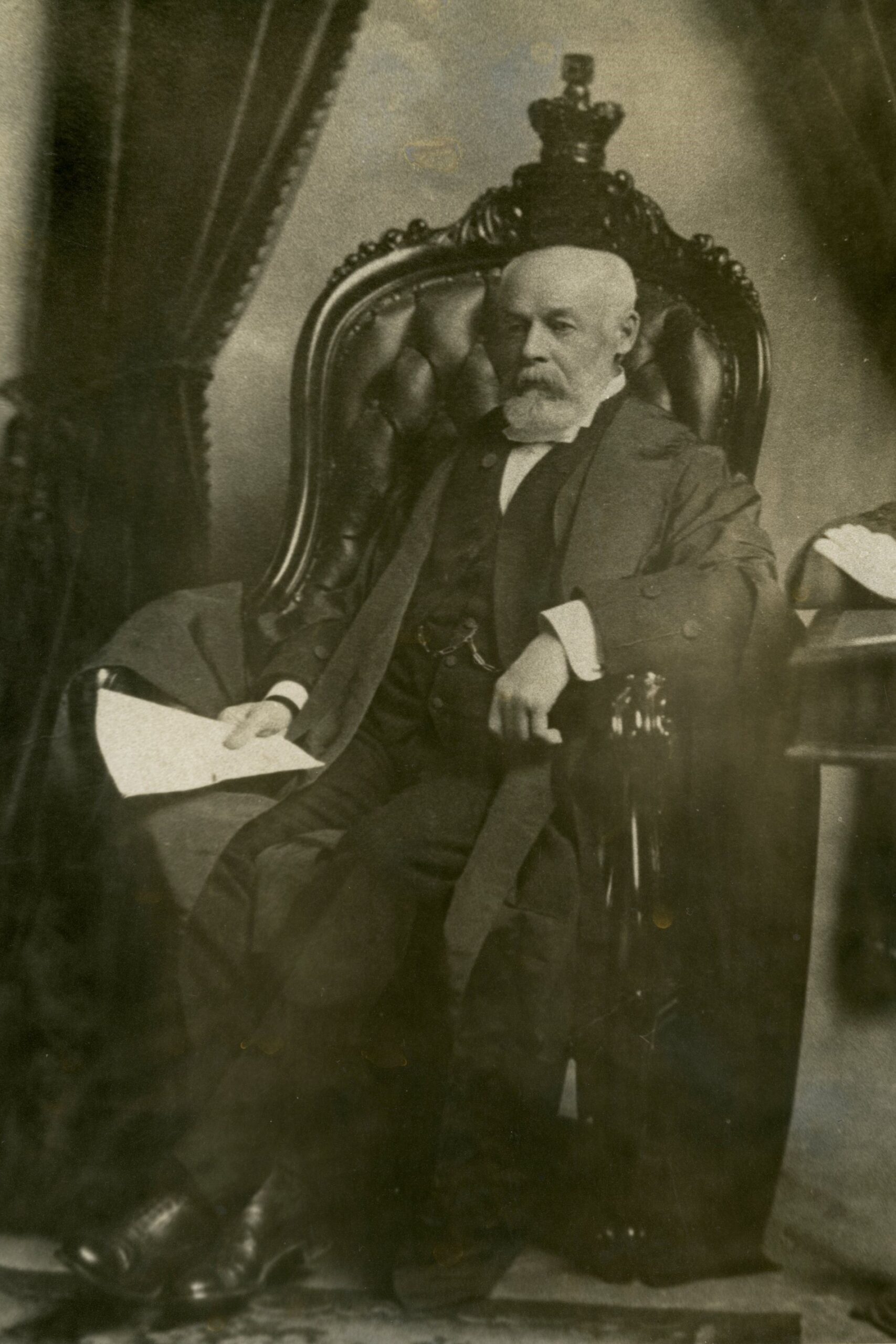

Private David Thomas, 1916. Courtesy Karen Schnerch.

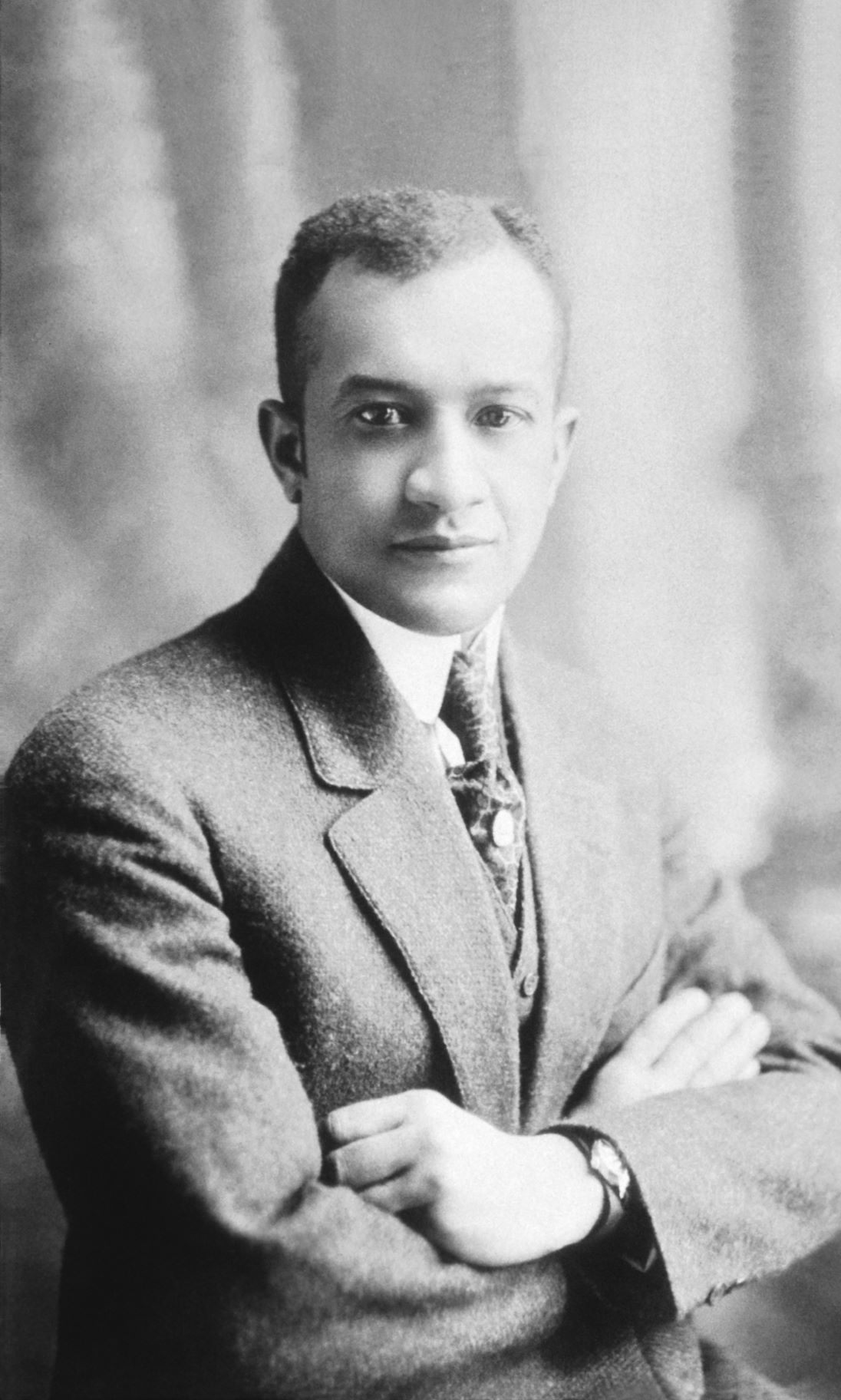

Private Thomas likely purchased this beautiful handkerchief in France. He sent it to his sister Mary Ann, who was living at Peguis Reserve. It is embroidered with a maple leaf and crown, and the words “Honour to Canada.” After learning of David’s death, she framed the handkerchief and it was displayed in Thomas family homes for over one hundred years. It was donated by the family to the Museum in 2020.

Framed silk handkerchief, 1917. H9-39-91. Image copyright Manitoba Museum

The central crest features a maple leaf inset with a crown and the word “CANADA.” Below, the term “Honour to Canada” is embroidered. H9-39-91. Image copyright Manitoba Museum.

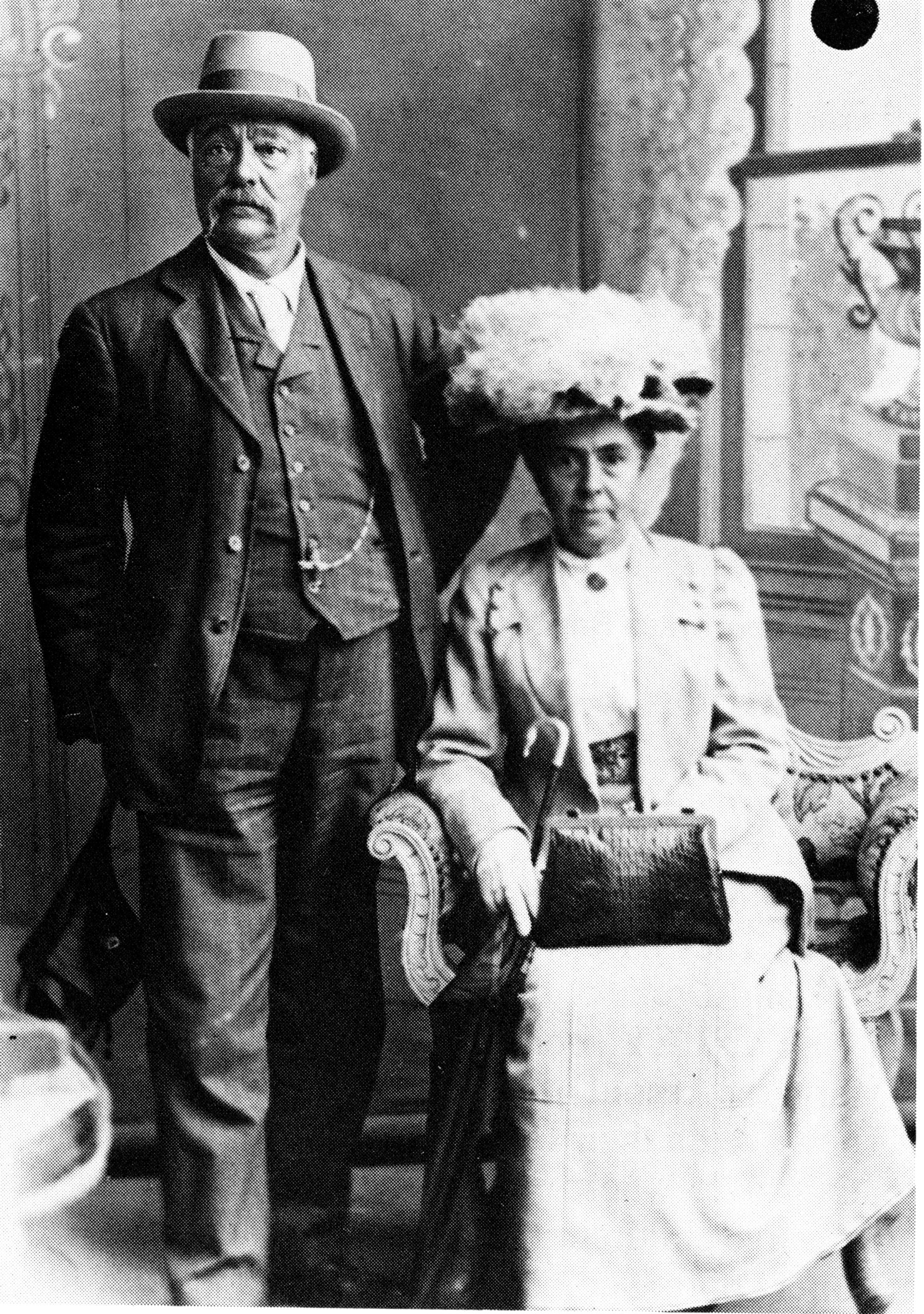

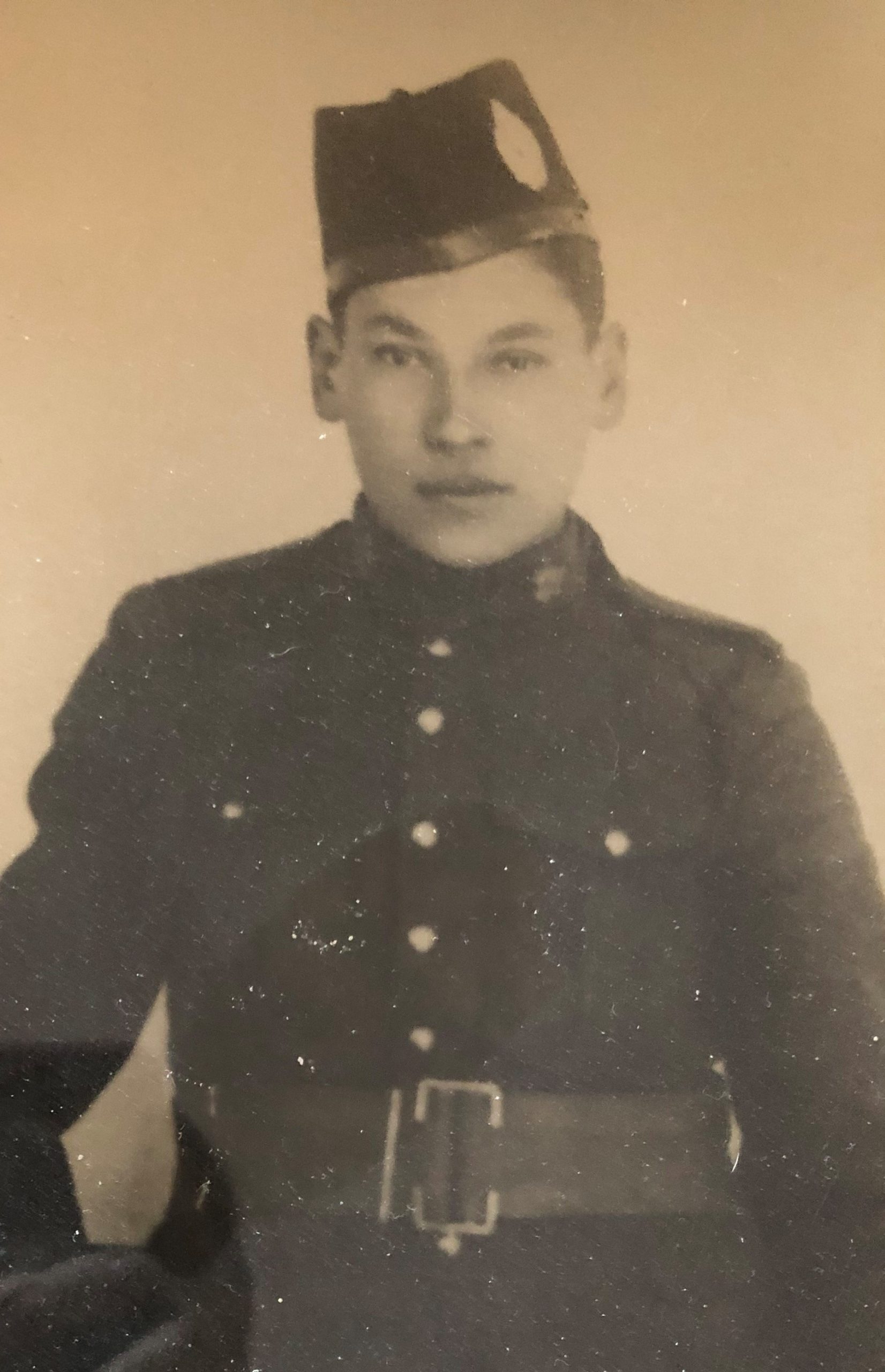

David Thomas’ sister Mary Ann, her husband Frank Smith, and their daughter in 1912. Mary Ann received the handkerchief as a gift from David. Image courtesy Terry Overton, grand-niece of David Thomas.

First Nations Soldiers

Over one-third of eligible First Nations men and women in Canada voluntarily enlisted during the First World War. More than 50 First Nations soldiers received recognition for bravery during combat. While there was a shared sense of camaraderie with non-Indigenous soldiers during the war, they returned, having been stripped of their Treaty rights, to a country that provided no compensation or support for First Nations veterans after the war.

The Battle of Passchendaele, where David Thomas was killed. Also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, the fighting raged on with British, New Zealand, Australian, and Canadian troops pitched against German forces for over three months. “Battle of Passchendaele – Mud and Boche wire through which Canadians had to advance.” CWM 19930013-512, Canadian War Museum