[Note: This blog contains descriptions and images that may not be suitable for sensitive individuals.]

In the Natural Sciences Department, we receive hundreds of specimens each year that will eventually be added to the permanent Scientific Collections. The Curators collect specimens through their many research projects, while other specimens are collected and donated by the general public. Most of these specimens require some very specific and time-consuming preparation before they can be in a state for which a researcher can use them. Fossils are exposed with precision tools, insects are painstakingly pinned, plants are pressed and artfully mounted, and mammal and bird study skins are skillfully prepared. Skeletons of vertebrates also require a very specialized preparation process that very few people are witness to.

Located deep within our Zoology research area is a small room that houses, what we affectionately call the ‘bug tank’. It is actually a metal 45 gallon drum that houses a beetle colony that we use to clean the very small or fragile skeletal specimens that may otherwise be damaged using other cleaning methods. These can include birds, small rodents such as mice and squirrels, snakes, frogs, toads and fish. One of my many tasks here at the Museum is to prepare skeletal specimens and maintain the beetle colony by keeping them healthy and well-fed.

The beetle species that we use in our colony is Dermestes maculatus (Identified by Reid Miller, 2016) from the Family: Dermestidae, a group that is commonly referred to as hide beetles. The adult beetles of this species are black in colour and can range in length from 5.5 to 10.0 mm. The larvae are brown in colour, hairy and pass through 5 – 11 instars, before they pupate into adults. They are natural scavengers and feed on a wide variety of material including skin, hair feathers, and natural fibers, such as wool, silk, cotton, and linen. With this in mind, I’m sure you can appreciate how careful we are at the Museum with keeping these beetles contained!

Specimens are readied for the beetle colony by first making sure that all of the data has been recorded, including its weight and the standardized measurements that are taken. The specimen is then de-fleshed by removing most of the muscle tissue, internal organs and eyes. It is then placed in a drying cabinet so the specimen does not introduce mold into the colony. Once completely dried, the skeletons are placed in rows on top of a layer of cotton batting within a cardboard box lid.

Each skeleton is placed with enough space between them so that if the beetles move any of the tiny bones while they are cleaning them, they don’t become mixed with the specimen next to it. The cotton batting provides a soft ‘matrix’ that the adult beetles and larvae travel through. I can then stack about 3 to 4 of these trays within the drum, which could translate to approximately 150+ small skeletons in the colony at any given time. Depending how active the colony is, skeletons can be completely cleaned in 7 to 14 days. The “Beetle Room” is kept at a cozy 28°C (83°F) to promote their life cycle and every few days I spray the trays with distilled water for added humidity. Then, I leave them alone to work their magic.

These are NOT free-range beetles!

The Dermestid beetles and their larva are just one of the types of insects that pose danger to our galleries, and the specimens and artifacts that are stored in the collections storage rooms. To ensure that none of our colony beetles escape, special considerations were built into the room. These beetles can burrow into many surfaces/media, so the walls are cinderblock, sealed with 3 coats of epoxy paint, instead of drywall. I’ve installed a perimeter of yellow tape around the room that has a layer of a sticky product applied to it (this product is similar to ‘Tanglefoot’ that is used to stop the Elm Bark Beetle on trees). The bung holes on the lid of the drum have two layers of fine mesh – this allows air exchange, but they can’t get escape.

Completed skeleton specimens are given a final cleaning with a small paintbrush to remove any debris or shed larval casings. They are then catalogued, and each bone including the skull and mandible are numbered and placed in an acid-free box with its data label. After a final freezing treatment to be sure they are completely free of anything live, they are ready to be filed into our main Scientific Collections storage room.

These specimens are then available for researchers and educational purposes.

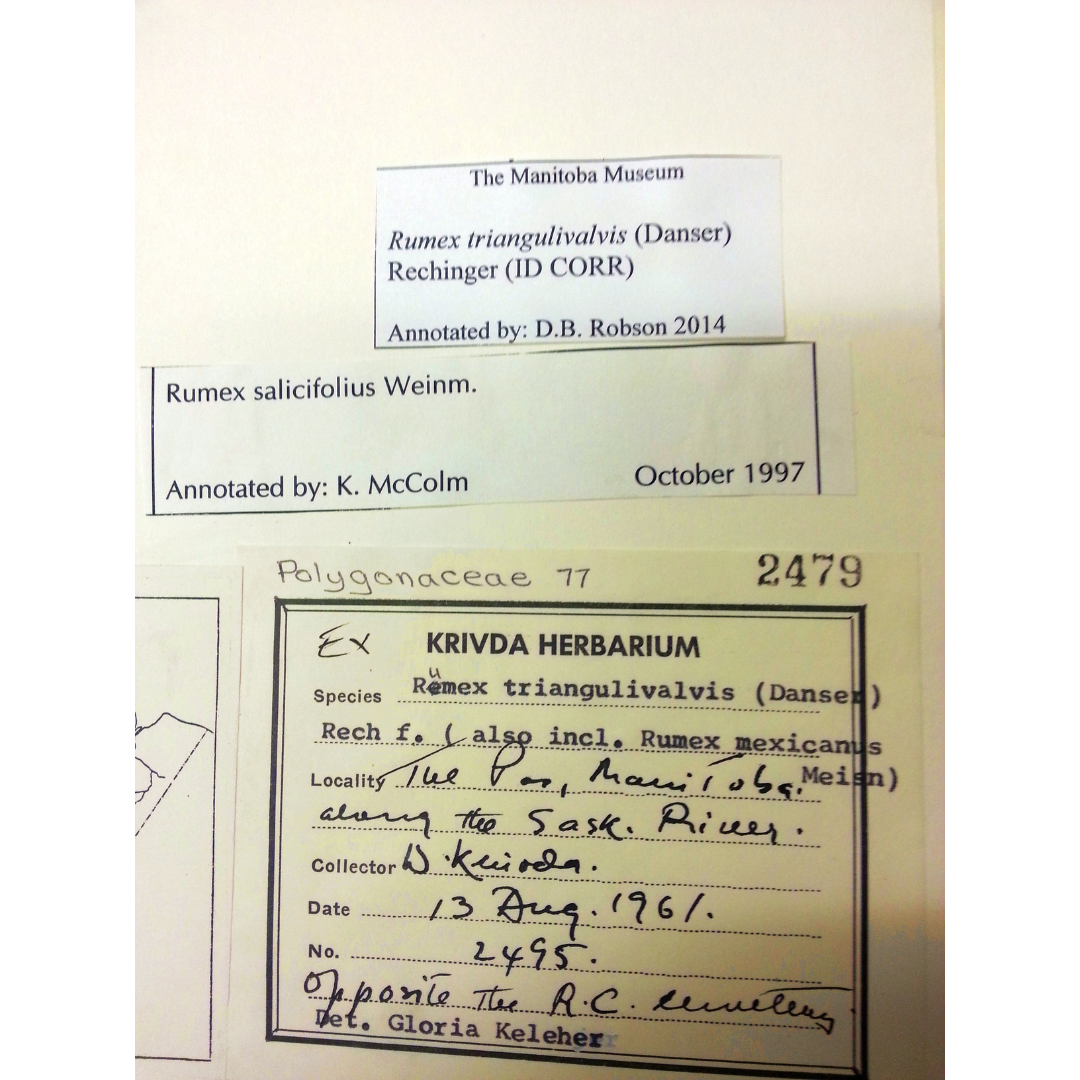

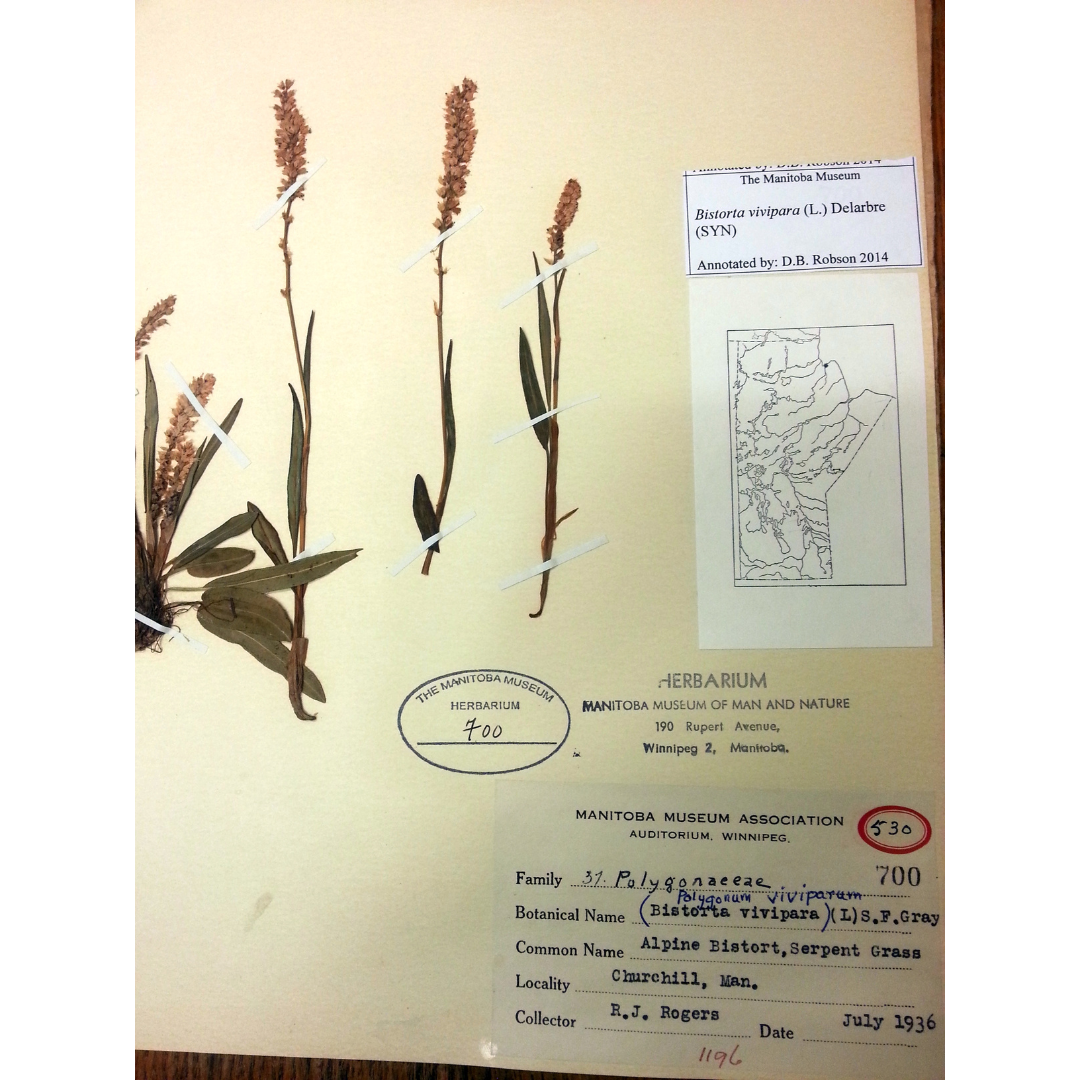

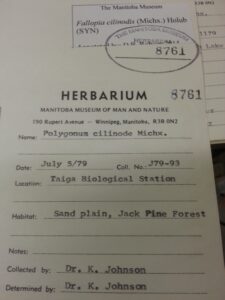

Recently, my husband asked me what I was working on, and when I told him I was updating the nomenclature for specimens in the Family Polygonaceae, he looked at me funny. I realized that as a non-biology person, my response was not that informative to him. It did not tell him that I was working on updating the official names of plant specimens, or even which plants they were, and it also did not make sense as to why their names would even change.

Recently, my husband asked me what I was working on, and when I told him I was updating the nomenclature for specimens in the Family Polygonaceae, he looked at me funny. I realized that as a non-biology person, my response was not that informative to him. It did not tell him that I was working on updating the official names of plant specimens, or even which plants they were, and it also did not make sense as to why their names would even change. When a living organism is recognized as being unique and different from other organisms, it is assigned a scientific name. This is the name that is used in the Museum’s database. A common name may be also included, but common names are not as useful or informative. This is because common names are different in each language. For example, the domestic dog is “perro” in Spanish, “chien” in French, “sobaka” in Russian, “gŏu” in Mandarin, “hund” in Danish, and “cane” in Italian. However, the scientific name for dog is Canis familiaris, and this is the same everywhere in the world.

When a living organism is recognized as being unique and different from other organisms, it is assigned a scientific name. This is the name that is used in the Museum’s database. A common name may be also included, but common names are not as useful or informative. This is because common names are different in each language. For example, the domestic dog is “perro” in Spanish, “chien” in French, “sobaka” in Russian, “gŏu” in Mandarin, “hund” in Danish, and “cane” in Italian. However, the scientific name for dog is Canis familiaris, and this is the same everywhere in the world.