Posted on: Tuesday June 25, 2013

Last week I went blitzing-BIOblitzing that is. What, you may ask is a BioBlitz? BioBlitz’s are biological surveys that are periodically held by conservation organizations or universities to identify the species of plants, animals and fungi that inhabit a particular tract of land. In Manitoba, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) periodically holds BioBlitz’s to identify the species on new properties that it acquires. The BioBlitz that I just participated in was of NCC’s recently acquired Fort Ellice property near the Saskatchewan border, just south of St. Lazare.

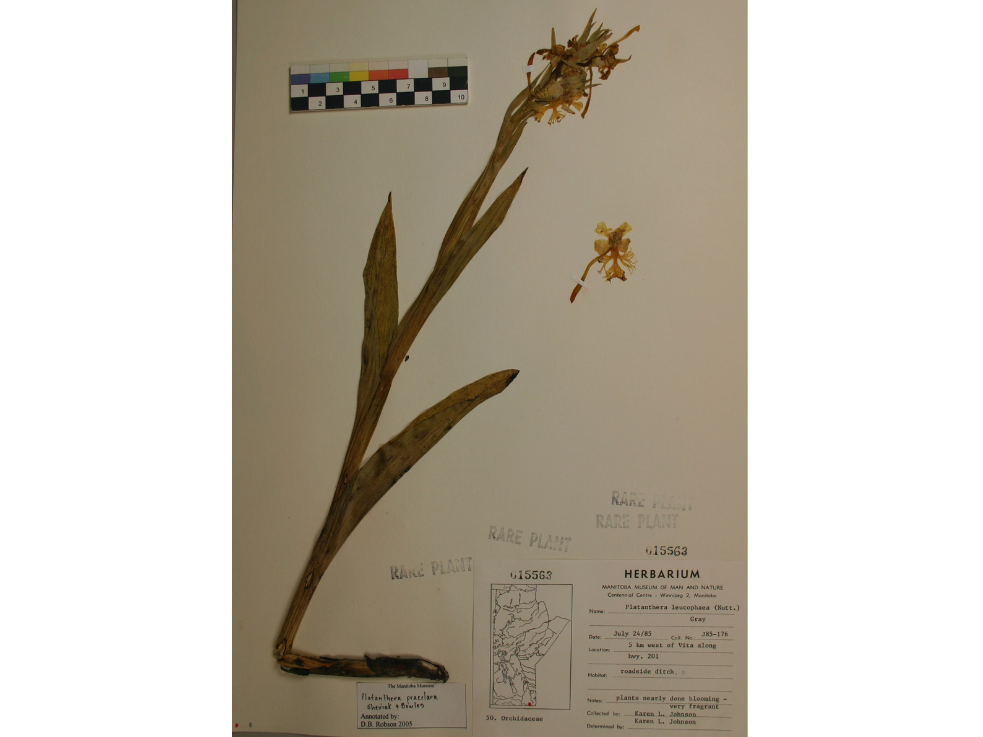

Having never been on a BioBlitz before, I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect. It turned out to be two days of hiking along the lovely Assiniboine River Valley, visiting with biologists I hadn’t seen for quite a while and seeing some beautiful rare plants, insects, and birds. It also meant getting covered in ticks and a boot-full of muddy swamp water but those are the normal hazards of field work.

Newly hatched Sphinx Moth.

Sand dunes along Beaver Creek.

Smooth Blue Beardtongue-a rare Manitoba plant.

Doing a survey with a large group of botanists made the event much more effective because if one of us didn’t know what a plant species was, someone else did. It was as if we had formed one big, really smart superbotanist! In addition to the plant people, there were also birders, a range manager, ecologists, bug catchers, a mammal expert, a couple of fungus guys, and even an archaeologist. We recorded all of the species we saw, and any plant, lichen, or fungus we couldn’t identify was collected to examine in the lab.

Highlights of the trip included spectacular sand dunes, a babbling brook, a recently hatched Sphinx Moth, mating Tiger Moths, and one of the largest morels I’ve ever seen. Now comes the sad part: waiting for the next BioBlitz so I can do it all over again!

Beaver Creek early in the morning.

A very large (20 cm long) Yellow Morel.

Tiger moths getting friendly!