Posted on: Wednesday September 23, 2015

By Dr. Graham Young, Curator Emeritus of Geology and Paleontology

Last week was the Museum’s “cleaning week”, during which we were closed to the public so that we could focus on getting our house in order. There was much recycling of paper, moving of old furniture, and scrubbing of walls in many parts of the Museum. Here in the Geology and Paleontology lab, we decided that this was the ideal time to file some of the fossils that had been catalogued in the past few months. Most particularly, we put away several hundred Ordovician age trilobites from the Stony Mountain Formation at Stony Mountain, just north of Winnipeg.

How did the Museum end up with hundreds of trilobites that needed cataloguing? Stony Mountain is one of the really important sites in southern Manitoba dating from the Late Ordovician Period, about 445-450 million years ago. During this time central North America was covered by tropical seas, and at Stony Mountain the limestone deposits are tremendously rich in fossils of marine invertebrates: corals, brachiopods (lamp shells), trilobites, and many other kinds of creatures.

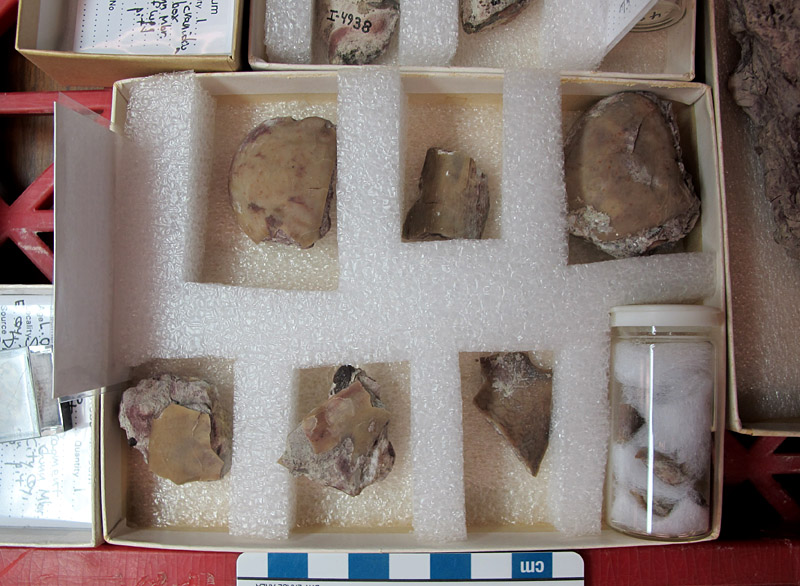

Image: Some of the catalogued trilobites, ready to be filed away.

Staff and volunteers from this Museum and its predecessor have collected fossils at Stony Mountain since the 1930s; over the years thousands of specimens have been catalogued to our collections, but very few of these were trilobites. A museum always collects more samples than can be catalogued quickly, and the Stony Mountain trilobites are somewhat complicated and consist mostly of small pieces*, so we had been holding onto them until there was time to consider which ones belonged in the permanent collection.

Image: Components of a trilobite that may belong to the genus Failleana (that’s a cranidium, the mid-part of a head, on the upper left).

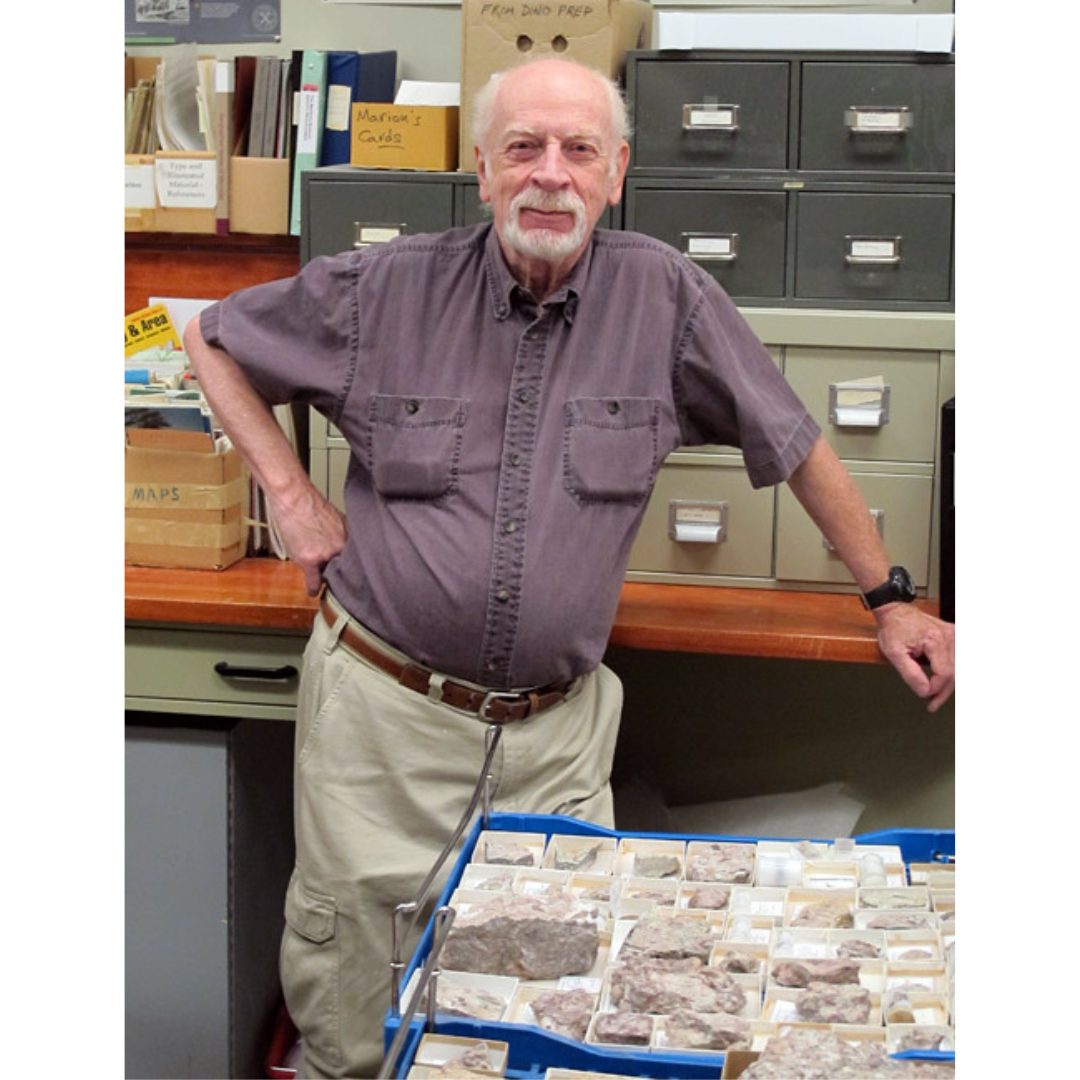

We knew that the Stony Mountain trilobites had been gradually “stacking up”, and volunteer extraordinaire Ed Dobrzanski and I had decided that we would devote some serious time and space to this project when we could. A few months ago the lab was looking relatively clear, so we laid out the hundreds of trilobites in trays and decided which ones were good enough to go into the permanent collection. I identified quite a few of them, but it fell to Ed to carry out the laborious, repetitive work of cataloguing each specimen.

The invaluable Ed Dobrzanski did most of the work on this project.

The specimens were filed away in our collections room.

When he was done, there were some 150 catalogued batches, all neatly laid out and padded. Once I had reviewed his records (we always double-check everything for accuracy!), we still had to find space in the collections, shifting the drawers in several cabinets to free up a block so that the trilobites could all be together and organized.

Finally, last week, we put the trilobites away! This may seem like a very big job for some small old fossils, but it means that many potentially important specimens are now properly recorded and stored, with the trilobites and their data readily available for future research or exhibits.

Image: One of the drawers of Stony Mountain trilobites.

An enrolled and incomplete cheirurid trilobite, possibly belonging to Ceraurinus.

Trilobite components: the tail (pygidium) of a cheirurid on the left, and partial mouthparts (hypostome) of an asaphid on the right.

*These trilobites are almost all incomplete because most trilobite fossils are from pieces of exoskeleton left behind when the animals moulted in ancient tropical seas. For the fossils at Stony Mountain, wave and current action on the ancient seafloor caused further abrasion and breakage.