Posted on: Tuesday October 20, 2015

By Dr. Graham Young, Curator Emeritus of Geology and Paleontology

It is exciting and interesting to work with the fossils of large vertebrate creatures, but this is a field with many complexities. During the fossilization of most vertebrates, the bone was replaced by other minerals, which makes the skeletal components both heavier and more brittle than they were during the animal’s life. For those of us working in the “back rooms” of museums, it can be very tricky to move these large, weighty, and fragile fossils as we prepare them, study them, or mount them for exhibit.

A few weeks ago, we had to perform one of the trickiest tasks associated with big vertebrates: flipping a skull. The large pliosaurid plesiosaur that was donated to the Museum by Wayne Buckley had been fully prepared by Wayne, so that the bones are completely removed from bedrock; their weight is supported by mounts or cradles (structures similar to the plaster field jackets). This makes the fossil much easier to exhibit or study, but it means that we have to ensure that we are fully supporting the skull whenever we move it, so that it doesn’t collapse or break. Since this particular specimen is unique and scientifically important, and since it has survived the past 90 million years or so in remarkably good condition, it is imperative that we take extra care!

The plesiosaur skull, as it appeared in our temporary exhibit last winter.

Janis Klapecki and Tamaki Sato, strapping the two cradles together.

In late September, we were visited by Dr. Tamaki Sato (Tokyo Gakugei University) and Dr. Xiao-Chun Wu (Canadian Museum of Nature), who spent several days here studying the skeleton for a scientific publication. Before they arrived, Debbie Thompson had been making the final exhibit mount for the plesiosaur; to allow her to do that work, the skull was resting in a temporary support cradle, with its “back” side (the side hidden during exhibit) facing up. We knew that Tamaki and Xiao-Chun would want to thoroughly examine both sides of the skull, and that at the midpoint of the week we would need to flip it so that they could study the “front” side.

Knowing this in advance, Debbie had prepared a second cradle that would fit onto the the side that was currently up, making this support out of wood, plaster, burlap, and other materials. Unfortunately for us, Debbie was on vacation when the visiting scientists were here, so it was left to the rest of us to ensure that the cradle was used as she had intended.

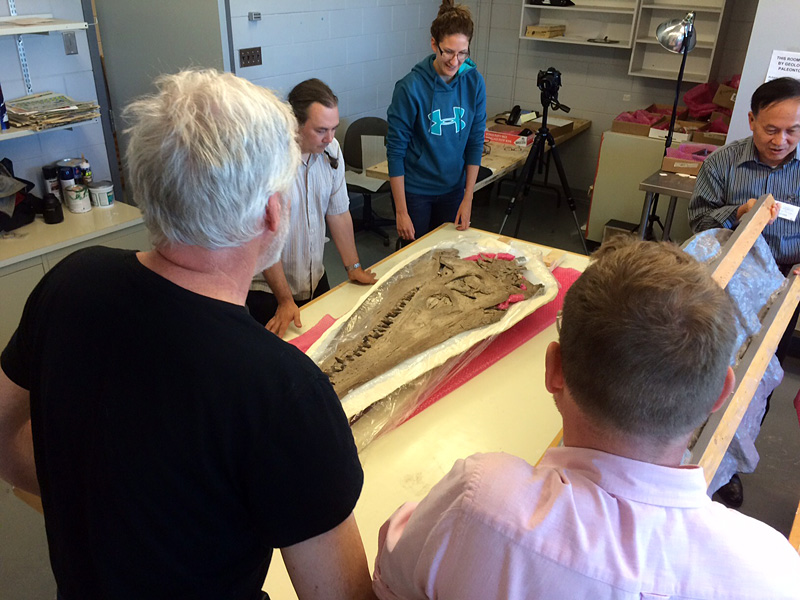

Before we could begin the “flip”, we had to turn the cradles so that they ran across the table. L-R: Kevin Brownlee, Amelia Fay, Tamaki Sato, Janis Klapecki, and me (photo by Stephanie Whitehouse).

Making sure we are all in agreement before we begin! Clockwise from left: Kevin Brownlee, me, Amelia Fay, Xiao-Chun Wu, Tamaki Sato, Janis Klapecki, and Roland Sawatzky (photo by Stephanie Whitehouse).

On the Wednesday afternoon, Collections Specialist Janis Klapecki and I went to the room where the plesiosaur is laid out, and with Tamaki and Xiao-Chun we fitted Debbie’s second cradle over the skull. The fit was perfect, so we wrapped sturdy packing straps around the two cradles, then tightened them until there was no give and the wood supports were flexing a bit. This tightness would ensure that the bones would move as little as possible during the flip.

When we were ready, we were joined by several of our curatorial colleagues, who had kindly volunteered their assistance. The skull and cradles were not immensely heavy, but the operation had to be done very steadily and smoothly, so it was best to have two or three people on each end of it. Once we had everything in place, and once we had discussed how we would do it, it only took a couple of moments to actually flip the skull.

When we removed the straps and exposed the skull, it was clear that the planning had paid off: the fragile fossil had survived it perfectly. Tamaki and Xiao-Chun could continue their scientific study, and the rest of us could return to our many other tasks. But we aren’t quite done with this sort of work yet: we will have to flip the skull at least a couple more times before it goes into a new permanent gallery exhibit next year.

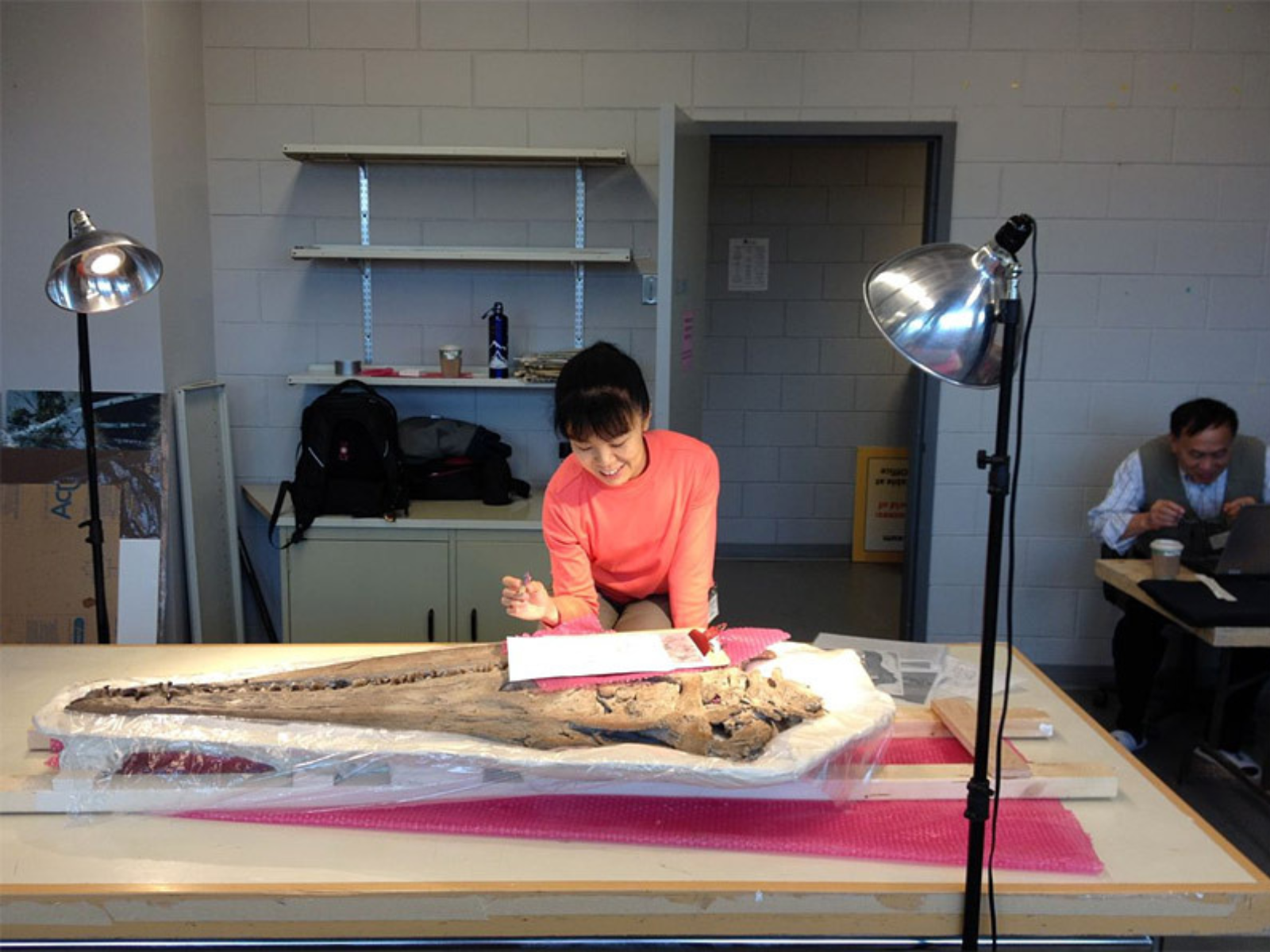

Image: The upper jacket is removed (photo by Stephanie Whitehouse).

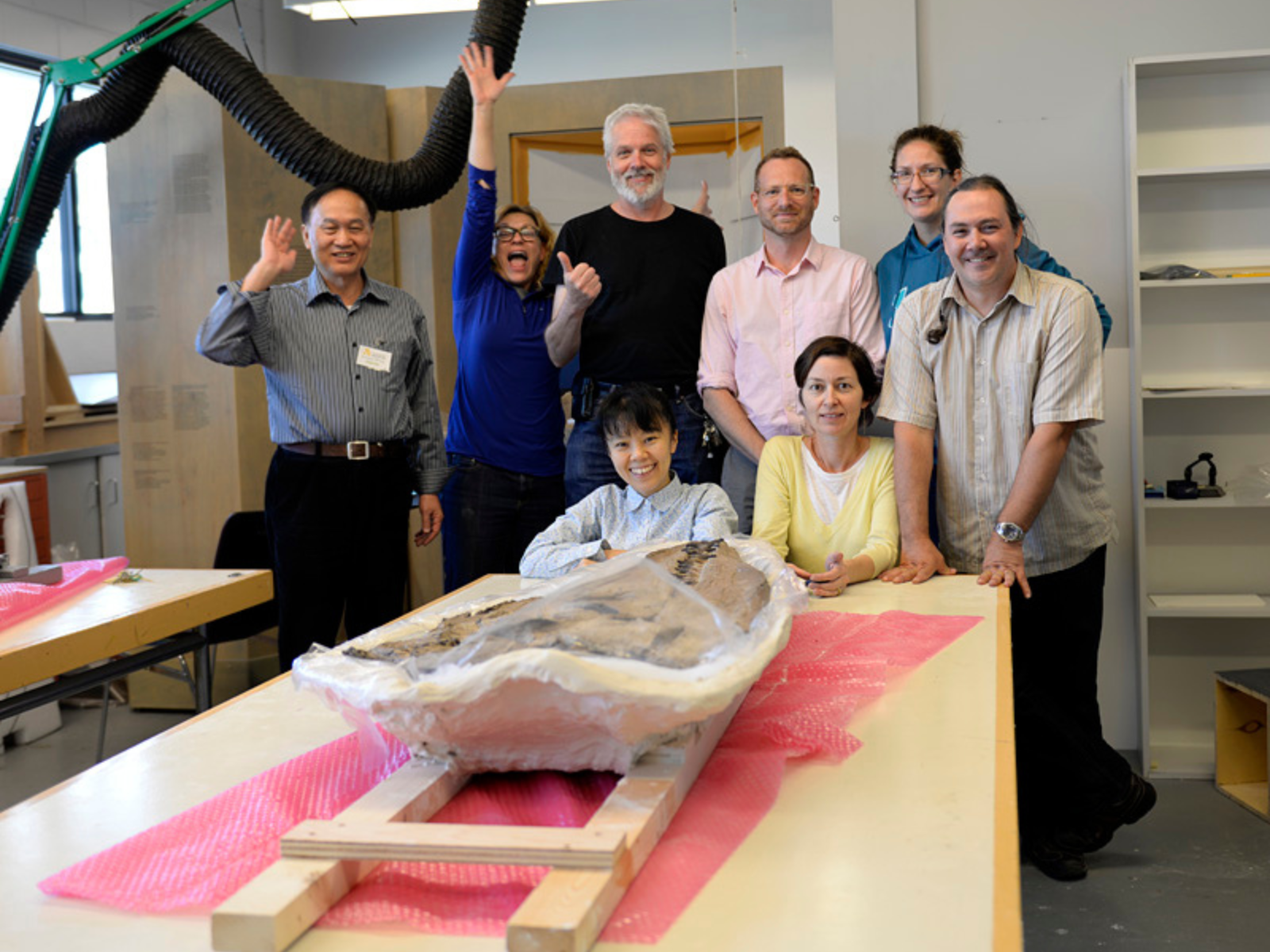

Success! L-R, front: Tamaki Sato, Stephanie Whitehouse; back: Xiao-Chun Wu, Janis Klapecki, me, Roland Sawatzky, Amelia Fay, Kevin Brownlee (photo by Xiao-Chun Wu).

Tamaki and Xiao-Chun return to their scientific studies.