Did you know that this bejeweled ram’s head in the HBC Gallery has wheels on the bottom? It’s a snuff mull from the 1800s.

Learn more about this peculiar artifact with Erin from our Learning and Engagement team!

Did you know that this bejeweled ram’s head in the HBC Gallery has wheels on the bottom? It’s a snuff mull from the 1800s.

Learn more about this peculiar artifact with Erin from our Learning and Engagement team!

It’s almost Valentines Day and the flower that most people associate with that holiday is bright red. Long-stemmed red roses have long been the flower of choice for people wooing their sweethearts. But if you’ve ever gone hiking in a wild Manitoba grassland or forest, you might have noticed that the roses we have here are pink, rarely white, but not red. In fact, there are no bright red wildflowers in our province. Why not?

To understand the lack of red flowers in Manitoba, we need to think about why flowers exist at all. Flowers are the reproductive organs of plants; they produce eggs and/or pollen. Since plants can’t move around to find a mate, they often use animals to move the pollen from one flower to another. Successfully transferred pollen fertilizes the eggs of the receiving flower. To attract animals, plants grow structures that animals will find attractive, like beautiful or unique scents, and petals with eye-catching colours. They also usually reward the pollinator with nectar.

Scarlet Paintbrush (Castilleja coccinea) is one of the reddest wildflowers we have in Manitoba, but it tends to be orangey-red rather than bright red. © Manitoba Museum

Wild Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) attracts hummingbirds, but butterflies, moths and bees are also important pollinators of this plant. © Manitoba Museum

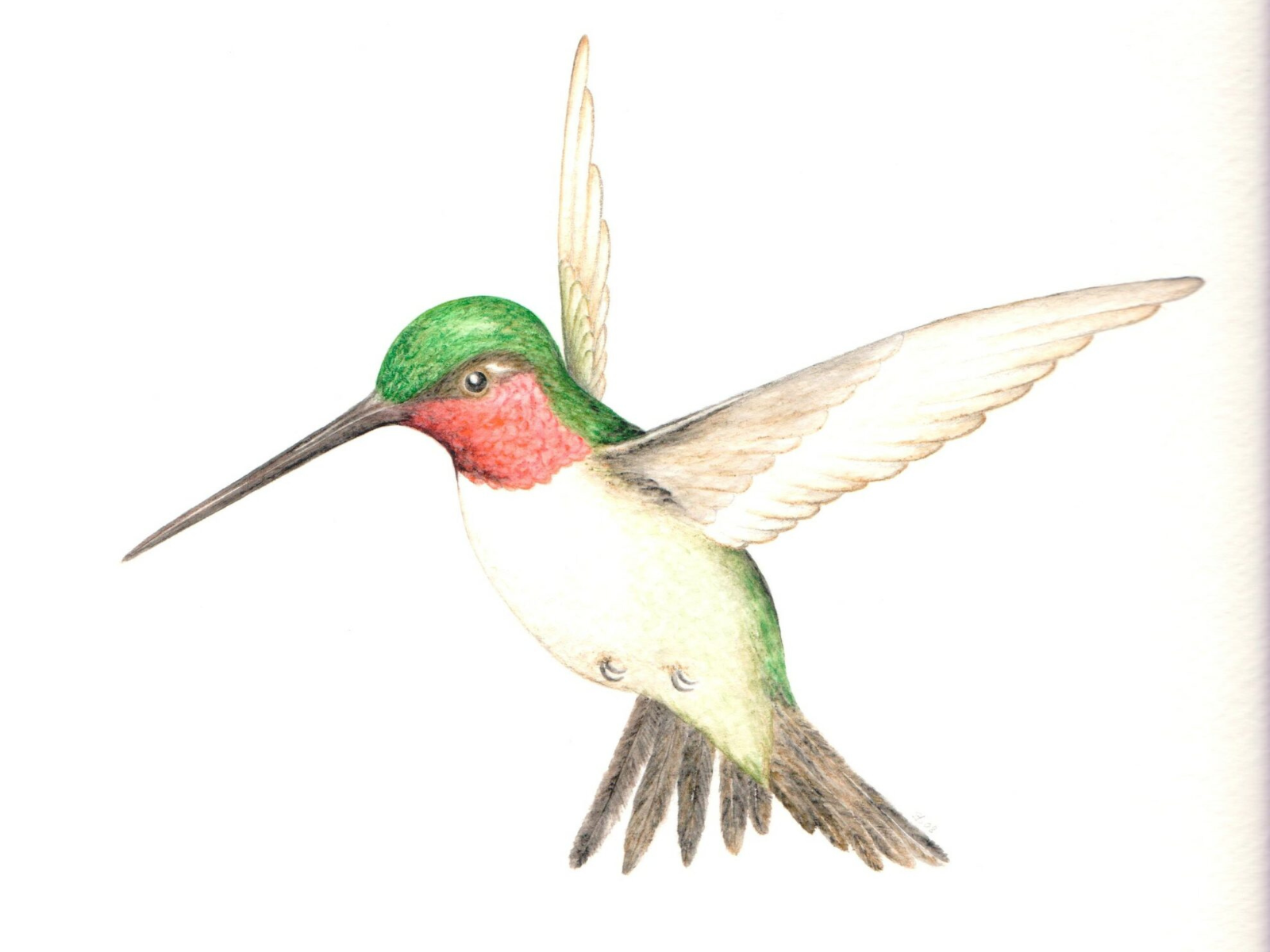

Colour exists because different surfaces reflect different wavelengths of light. Light is made up of a whole spectrum of colours, evident in a rainbow or when light shines through a prism. Just like some animals have a better sense of smell than others, they also see things differently. Birds and humans can see red flowers quite well, but most insects cannot. To an insect, red is difficult (though not impossible) to tell apart from green leaves. For this reason, areas where birds are common pollinators (such as tropical rainforests) tend to have lots of red flowers. Areas with mostly insect pollinators typically have lots of yellow and violet flowers. In Manitoba, our only bird pollinators are hummingbirds, the most common being the Ruby-throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris).

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (Archilochus colubris) move pollen from flower to flower in exchange for a nectar reward. Illustrated by Silvia Bataligni © Manitoba Museum

Insects are the most abundant pollinators in Manitoba, so most of our flowers are highly attractive to bees, butterflies, moths, flies, wasps and/or beetles. Flowers that are orange, yellow, blue and violet are most attractive to insects, as these colours are readily visible to them. However, unlike humans, insects can also see into the ultraviolet (UV) range. This ability explains the presence of so many, seemingly white flowers in the province. Flowers that we see as pure white or plain yellow, actually usually reflect UV rays, and look much different to insects than to us. White flowers are also often pollinated by moths, because white is more visible in moonlight than any other colour.

Small bees and flies, not birds, pollinate our wild roses, including Prairie Rose (Rosa arkansana). © Manitoba Museum

Many insect-pollinated plants, like Dandelions (Taraxacum sp.) have patterns that are visible only under UV light (left) © Wikimedia Commons CCA-SA 4.0

Humans have been cultivating roses for thousands of years. In the process, we selected features that we find attractive but that make them largely unattractive to pollinators. Colour is one factor. Insect pollinators do not usually visit red roses because they can’t see them very well. Further, cultivated roses have many, densely packed petals (not just five like the wild ones), that cover up the pollen-containing anthers, making them difficult for pollinators to access. So, the end result is that these beautiful flowers now function only as aids to human, not wild, romance.

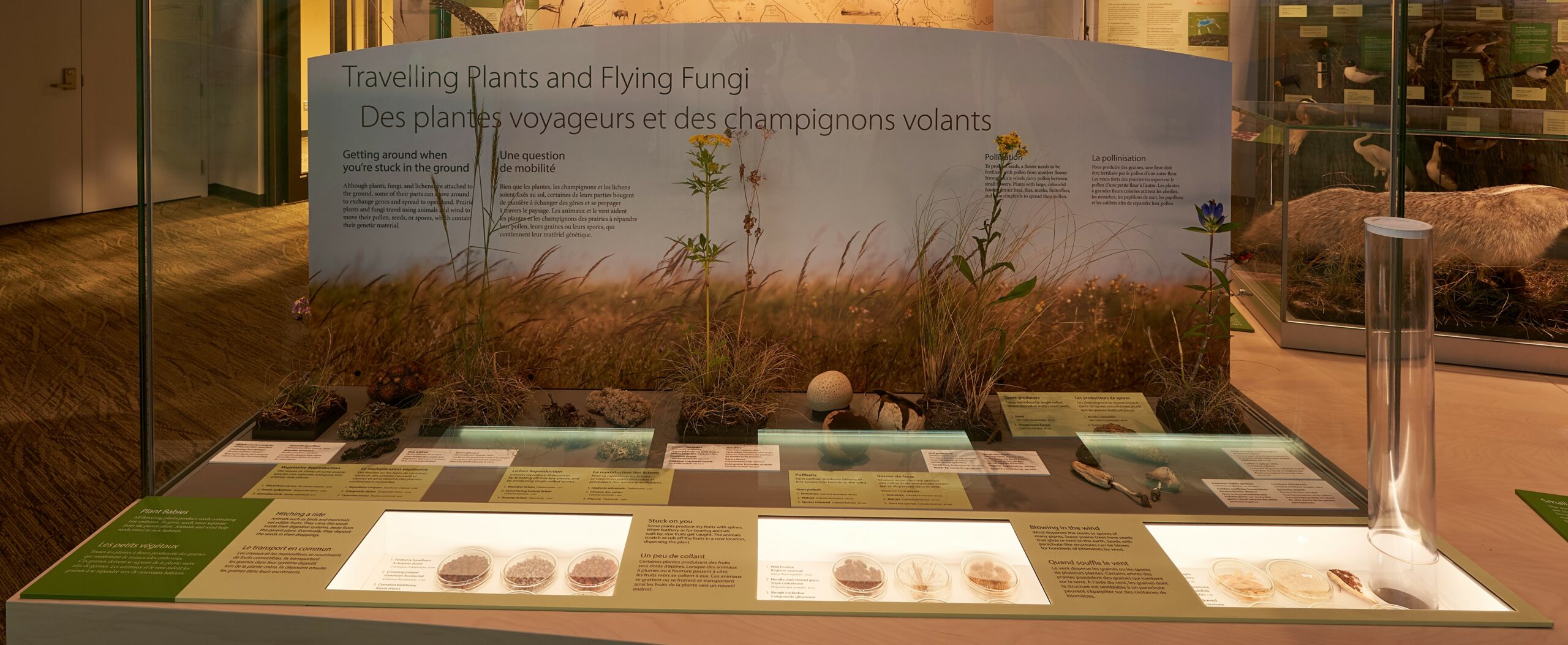

The Manitoba Museum’s new Prairies Gallery has a whole exhibit on pollination where you can see what native pollinators look like. © Ian McCausland/Manitoba Museum

By Mike Jensen, Planetarium/Science Gallery Programs Supervisor

When thinking of activities to do on a bright Winter’s day, science doesn’t usually come to mind. Surprisingly, science is at work with almost every fun pastime you can conduct out in the snow. You just need to know what to look for!

Of course, the first thing you think about as you zoom down a snow-covered hill on your favorite toboggan is physics, right? Well, it should be, because the laws of physics are actually in the driver’s seat when you are careening down a slope with no brakes. Next time you hit the slopes, conduct some experiments.

Once you are done experimenting with your sled, shore up your engineering skills by building a snowman. Surprisingly, it’s not as simple as you think. Here are some science and engineering factors to consider when making Frosty in your front yard.

After you’ve had your fill, come put your new-found science and engineering skills to the test at the Manitoba Museum’s Science Gallery. Design and build your newest creation at the LEGO brickyard, or see if you can be the first to cross the finish line at the Engineered for Speed Race Track!

Did you know that this quilt crossed the Atlantic during war-time only to find its way home over 70 years later?

When the weather turns cold, many of us reach for the warmth and comfort of a handcrafted quilt or afghan. During WWII, local volunteers gathered in Steep Rock, MB to create Red Cross quilts for civilian victims of the war. Across the Atlantic, at Dudley Road Hospital in Birmingham, England, a Matron passed their gift on to Cynthia (Betty) Craddock. Her husband Joe was serving in the army when their only son Anthony was born in 1945.

Anthony’s earliest memories are “of this quilt being on my bed and keeping me warm when times were hard. With no central heating, frost would often appear on the inside of the window.” The young Anthony remembers reading the message on a tag on one corner of the quilt. Betty treasured the gift for many years until finally they decided that it was time for the quilt to be sent home.

You can see the quilt along with photos of Betty and Anthony Craddock in our Parklands Gallery.