When the Ukrainian Canadian Legion Branch 141 building closed on Selkirk Avenue at the end of March 2022, Vladimir Putin’s military invasion of Ukraine was a month old. I visited the Legion building and was shown the flag of Branch 141, and I was struck by the power of the symbols, given the current conflict.

Though this flag has its origins among Canadian veterans from the Second World War, history has come around to give it new symbolic power.

Ukrainian Canadian Veterans Branch 141 flag, likely designed in the late 1940s.

The flag includes the Ukrainian flag colours, with light blue above, and yellow below. In the centre is a dark green, organic maple leaf, and within this lies the now famous Tryzub, or Ukrainian “trident” symbol. A green maple leaf might be surprising, but today’s abstracted red maple leaf on the modern Canadian flag was only adopted in 1965, after the Branch 141 flag was created. The organic maple leaf was first adopted by Lower Canada in the 1830s, and has been associated with the Canadian military since 1860.

The golden Tryzub currently used as a symbol of Ukrainian independence has a much deeper history. It is based on symbols over 1000 years old that appeared on coins minted for Volodymyr the Great of Kyiv in 980 CE. The Tryzub was adapted for use in the coat of arms of the Ukrainian National Republic in 1918, after the fall of the Russian Empire during the First World War. When Bolshevik forces took over the country in 1920, the Tryzub was replaced by Soviet symbology, most notably the hammer and sickle. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic existed from 1920 until 1991.

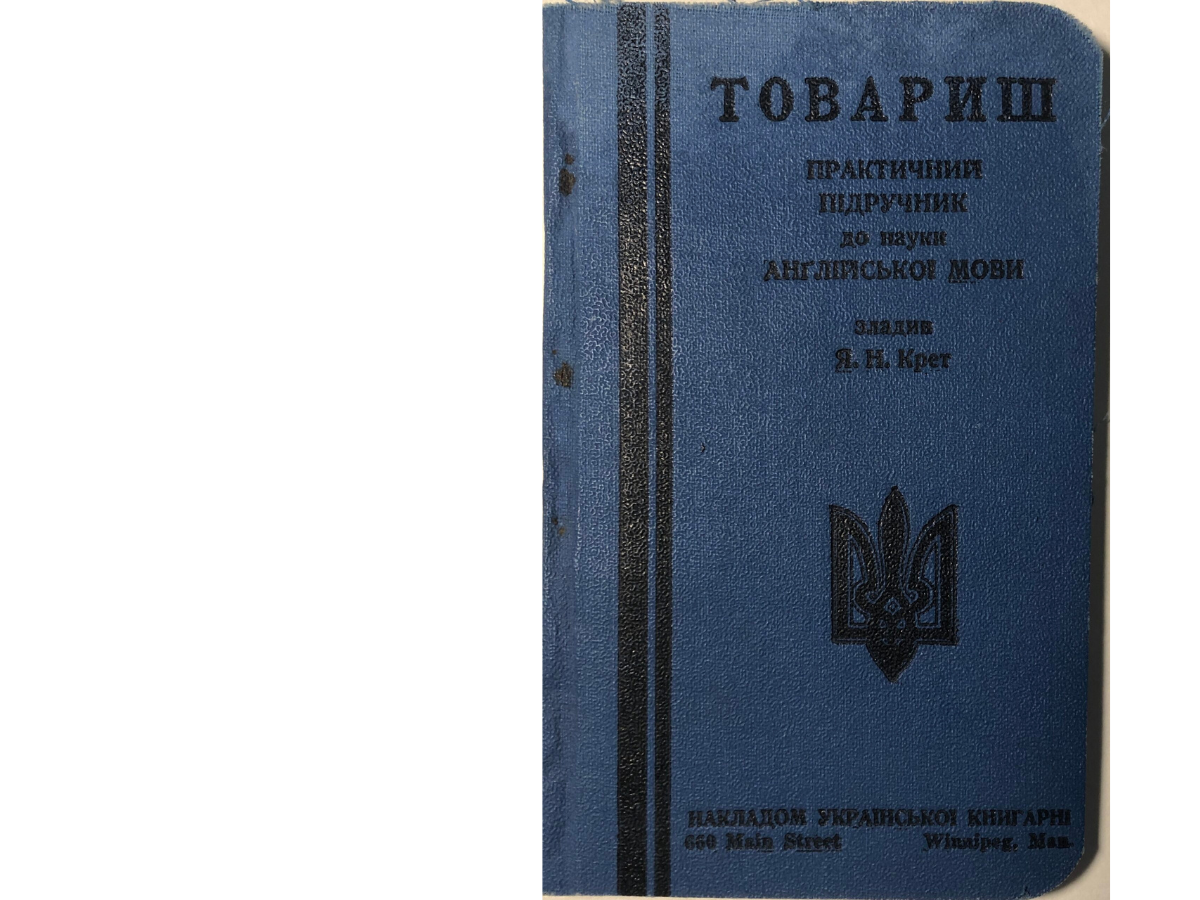

The Tryzub is seen here on the cover of a Ukrainian language phrasebook published in Winnipeg in 1931.

The publisher was Frank Dojacek, a Czeck immigrant to Winnipeg who started the Ruthenian Booksellers and Winnipeg Music Supply store on Main Street in the 1910s. He supplied products to the large Eastern European population in Manitoba, and knew seven languages. H9-7-23

After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine once again declared its independence, and the Tryzub was instituted as part of the “small coat of arms” in 1992. It has continued as a symbol of independence for 30 years.

Today, during the war between Ukraine and Russia, the Tryzub is recognized by many as a symbol of Ukrainian resistance to aggression and invasion. Seeing it joined with the maple leaf on the Ukrainian Canadian Veterans flag suggests new symbolic associations, such as the current support of Ukraine’s war efforts by the Canadian government, as well as Ukrainian Canadian heritage in Canada.

It’s important to note that national symbols often get hijacked by nationalist groups, far right elements, and other extremists for their own purposes. Symbols are open to interpretation, but at the same time act as a focus for emotions.