Post by Marc Formosa, former Collections Technician of Natural History

A current and ongoing problem for museums is collection storage space. Maximizing space for expanding collections requires Tetris-like problem solving. We are always looking for ways to make the most of the space we have, while improving the long-term preservation of the objects in the collection.

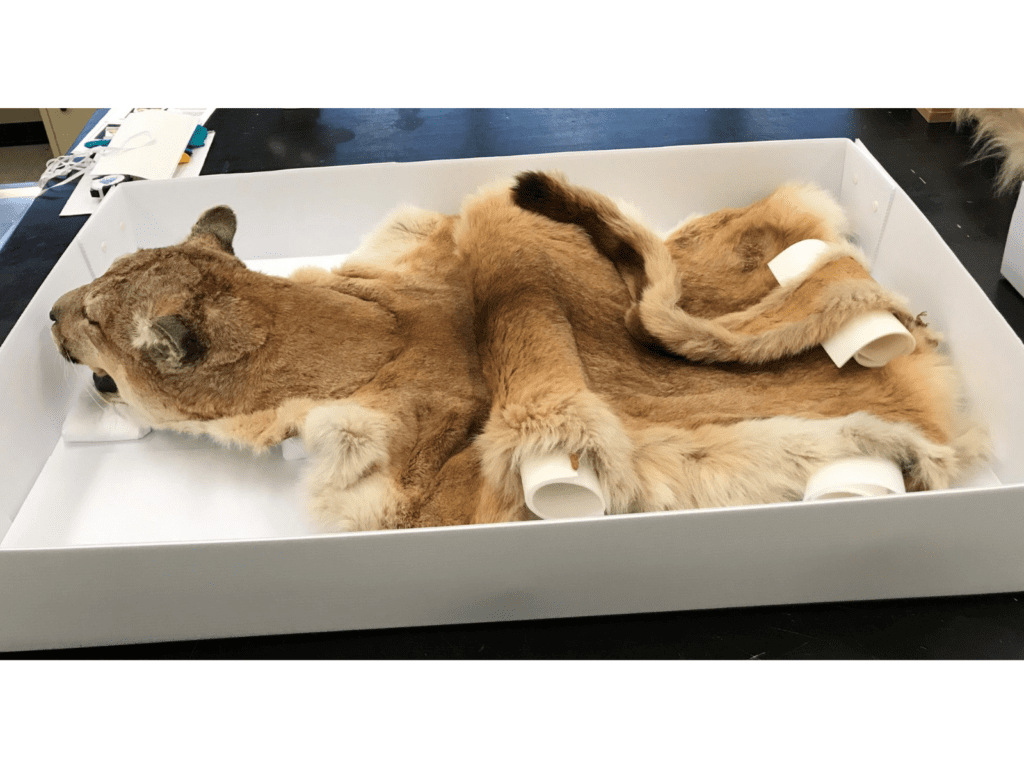

In the spring of 2021, I had the chance to virtually attend the joint American Institution for Conservation (AIC) and The Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections (SPNHC) conference. A presentation by Laura Abraczinkas and Barbara Lundrigan titled “Storage Improvements for Tanned Mammal Skins at the Michigan State University Museum” covered folding techniques for large mammal skins to reduce the space they take up, while also discussing how to protect parts of the skin like the paws and head from potential damage while folded. The information in this presentation inspired a rehousing project for polar bear, grizzly, cougar, grey wolf, and leopard skins in the zoology collection.

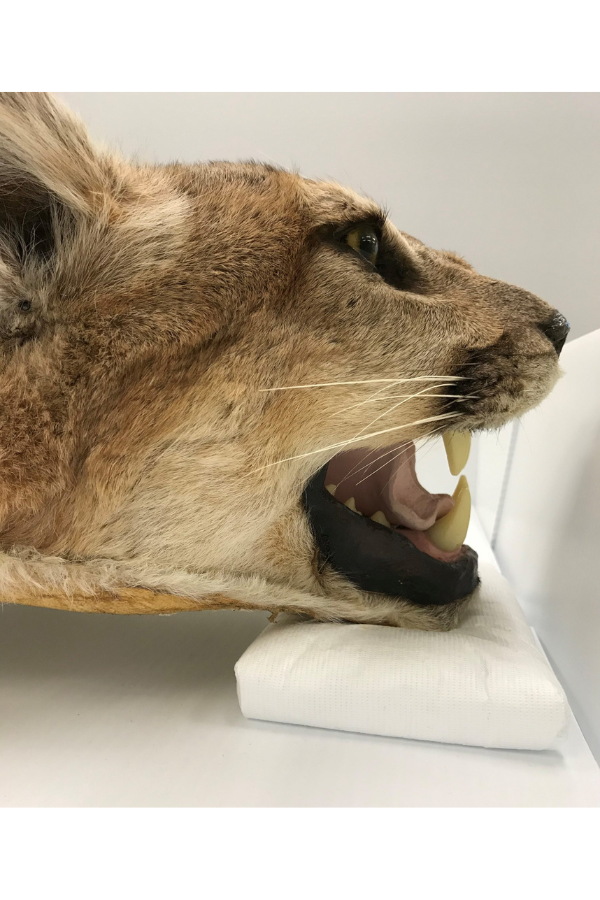

Most of the skins that were rehoused as part of this project were attached to a felt fabric backing. This is typically done if a skin is going to be used as a rug. The head is stretched around an armature (made from a variety of materials including wood, foam, and plaster) to maintain a semi-life like position, but it also makes the head quite heavy. The mouth and teeth are created by the taxidermist and are not part of the original mammal.

Marc with the grey wolf skin getting it ready for rehousing. Image: © Manitoba Museum

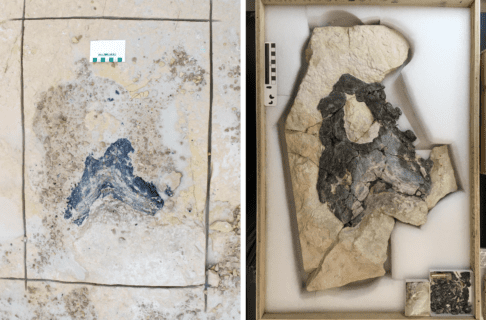

For each mammal, I started by creating custom mittens for their paws out of Tyvek – a lightweight and durable nonwoven material that is resistant to water and abrasion, and has good aging properties. I used a sewing machine, for the first time, and stitched the Tyvek together with cotton thread so each mitten fit snug around each paw. (Pictured below, left)

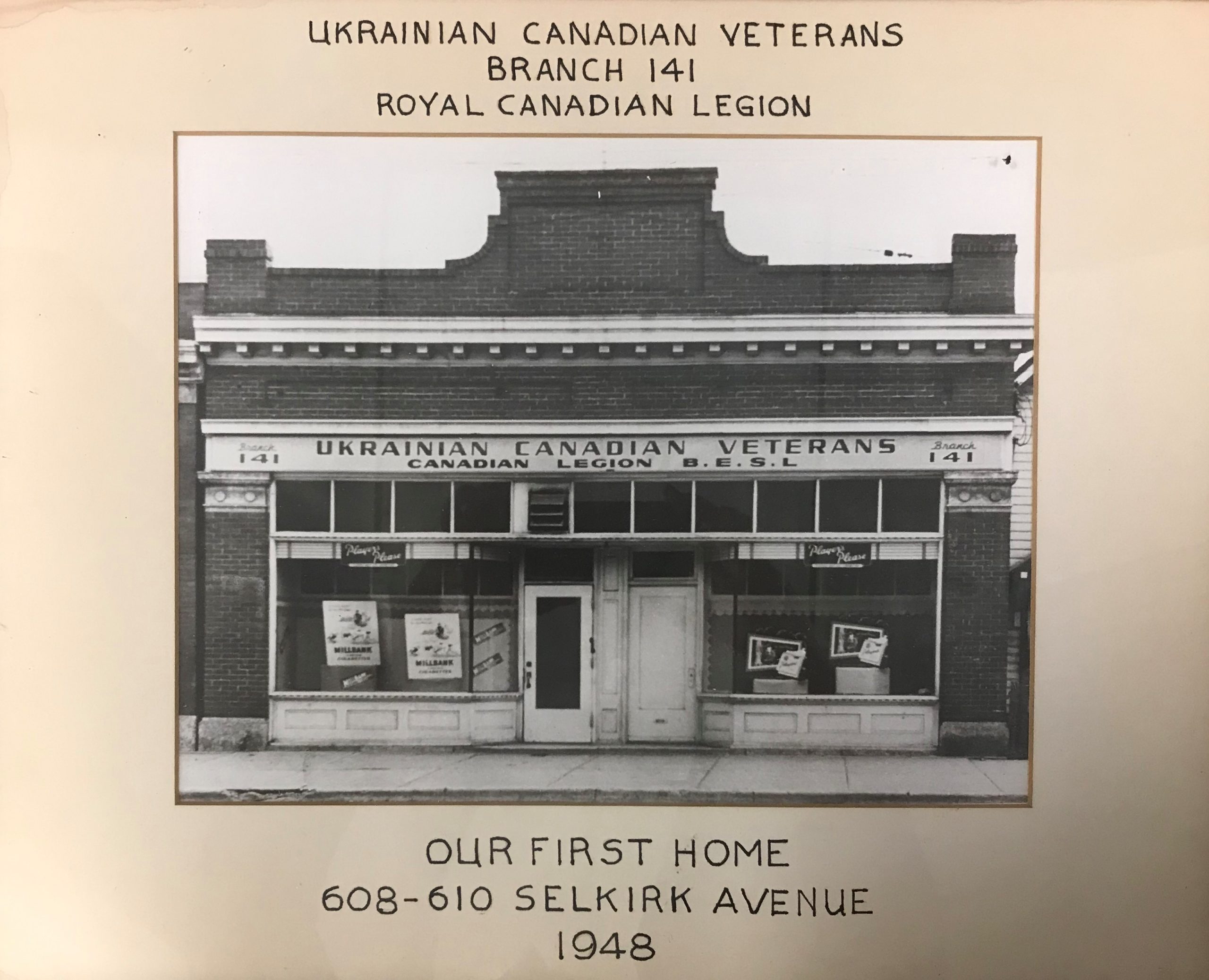

The folding method can be simply described as a ‘bear’ hugging itself. Every fold is padded out with volara, a smooth closed-celled polyethylene foam, to add support and prevent creases forming in the skin. Finally, the head sits on top of the folded skin, again padded out with volara. (Pictured below, right)

The stitched Tyvek mittens fit snuggly on each paw. Image: © Manitoba Museum

Cougar skin folded and padded with volara supports inside a coroplast box. Image: © Manitoba Museum

For the cougar and leopard heads, custom pads were created for each head to sit on away from the body in order to alleviate stress and prevent the skin from creasing on the neck where the head armature meets the skin. (Pictured below, left)

The skins were individually wrapped in polyethylene sheets as an additional barrier from dust accumulation and insects. Custom boxes were built out of coroplast which allow for the skins to be more easily handled as they move in and out of their new home in the collections storage vault (pictured below, right). Overall, this rehousing project improved the preservation of the skins and their storage method. It freed up space, but free space does not remain long in museum collections storage spaces.

The cougar’s head is supported with a soft Tyvek-covered chin pillow. Image: © Manitoba Museum

The rehoused large mammal skins are safely stored in cabinets inside the collections storage vault. Image: © Manitoba Museum