Posted on: Tuesday June 28, 2016

By Maureen Matthews, past Curator of Anthropology

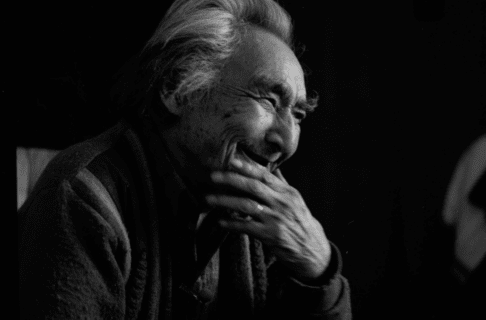

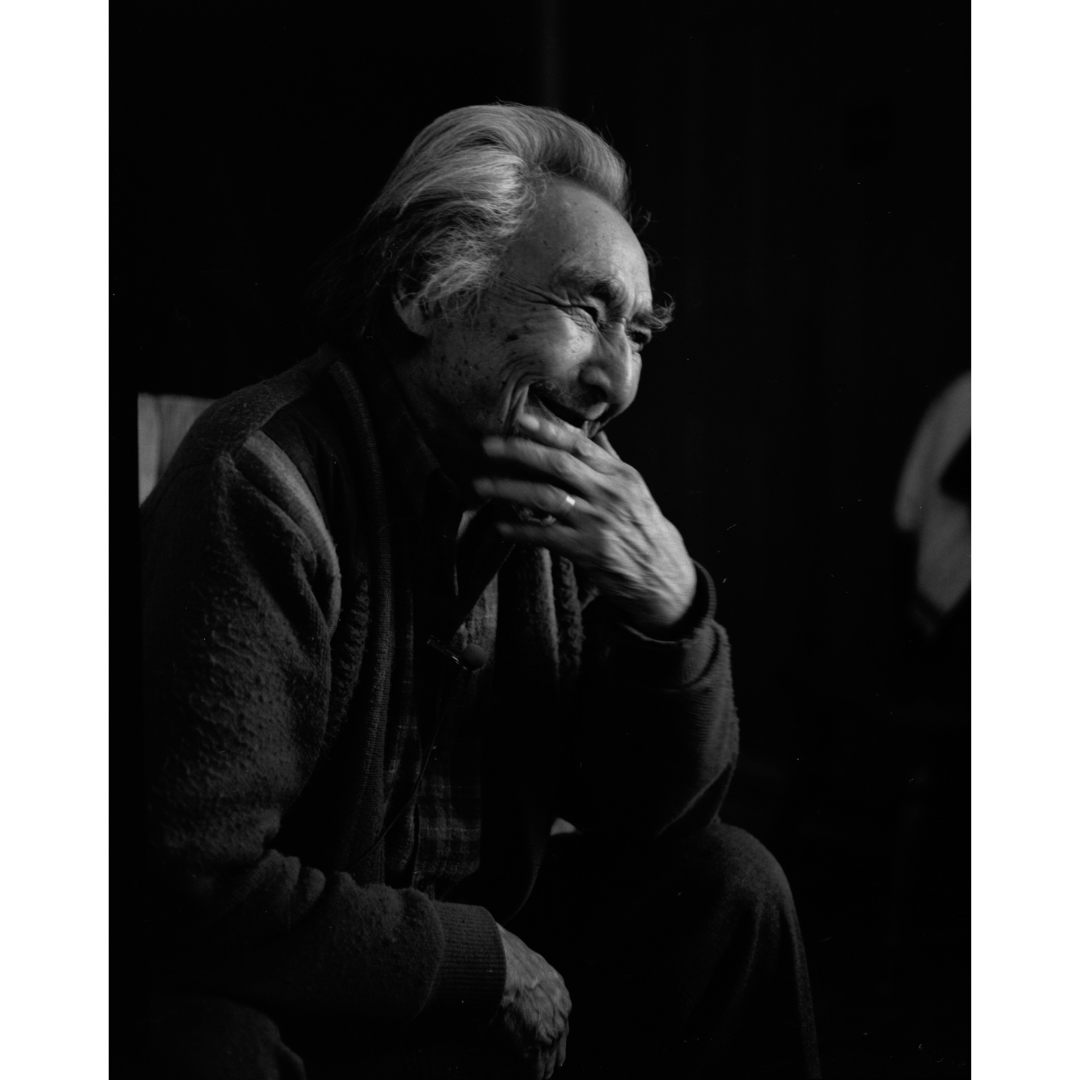

Jacob Owen of Pauingassi was always cheerfully willing to explain the complexities of Ojibwe history and philosophy with stories from his own life. Margaret Simmons, who conducted this interview, was the Director of Education in Pauingassi at the time. She is a warm and open person with a positive genius for respectfully conversing with old people and her unique talent made my visits to Pauingassi and over 300 hours of Anishinaabe language recordings possible. The equally brilliant and even more patient Anishinaabe linguist, Roger Roulette, has been gradually transcribing and translating the Pauingassi recordings. He just finished this one today and it contains a remarkable discussion in Anishinaabemowin about the old Anishinaabe and their skill at making pots out of clay.

Jacob was over 90 at the time of the interview, the oldest man in the community. He spoke very little English and had lived his whole life in Pauingassi. He most definitely had not read scholarly reports about archaeological discoveries of 500 year old clay pots made by his ancestors and yet, here he is, talking about how incredibly skillful his ancestors were at making these beautifully decorated pots. The conversation veers off after this, in part because Margaret, a very good modern speaker, doesn’t know the word for “clay, waabigan” but this short quote from Jacob’s conversation is an indication of the extent to which one can rely on First Nations oral historical accounts for the truth about the distant past. By the way, Roger says that the verb to fire a pot is zakizo (va) to burn an animate thing. The idea of a kiln is expressed in the verb boodawaash (ca) which means to superheat something animate.

Image: Jacob Owen, Pauingassi Manitoba. 1996.

| Original (Anishinaabemowin) | Translation (English) |

| JO: Daabishkoo, gigikendaan ina ‘iwe gaa-ijigaadeg, aadizookaanag gaa-ijigaadeg? | JO: It’s like…you know what they mean by that, what they mean by aadizookaanag (legendary heroes)? |

| MS: Eya’. | MS: Yes. |

| JO: Daabishkoo mii gaa-inendaagoziwaad igiweniwag Anishinaabeg nishtam gaa-gii-bimi-ayaawaad. Bigo gegoon gaye ogii-ozhitoonaawaa’. Wiinawaa bigo. | JO: The first Anishinaabeg that existed, this is what they’re comparable to (the legendary heroes). Also, they were able to make anything. They, themselves. |

| Nashke aya’aa, akik. Waabigan gaa-onji-ayaawaad. I’iya’aawan nda gii-onizhishiwag. Eji-, eji debakamig gidaa-ikid e-gii-mookaakizowaad. Ndawaaj gii-onizhishiwag. | For instance, a pot (vessel) (noun animate). They made them from clay. My, they were beautiful. You would have said they were incredible. The visible images (on the pots), undoubtedly, they were beautiful. |

| MS: Aaniin dino akikwag? Asiniiwi-akikwag? | MS: What kind of vessel? Stone vessels? |

| JO: Bibagiziwag. Gii-bibagiziwag. Waabigan daabishkoo. I’iwe dash waakaa-aya’ii gii-mazine’aawaad gaye, ndawaaj gii-onizhishiwag. | JO: They’re thin. They were thin. It was the nature of clay. However, they had images/patterns around (the pot). My, but they were beautiful. |

| Zhigwa ayi’ii naanaagadawendamaan, awegodogwen gaa-omookomaaniwaad nishtam? | Well, when I think about it, I wonder what they used for a knife (to incise the designs) at that time, at the outset? |