Posted on: Monday November 16, 2015

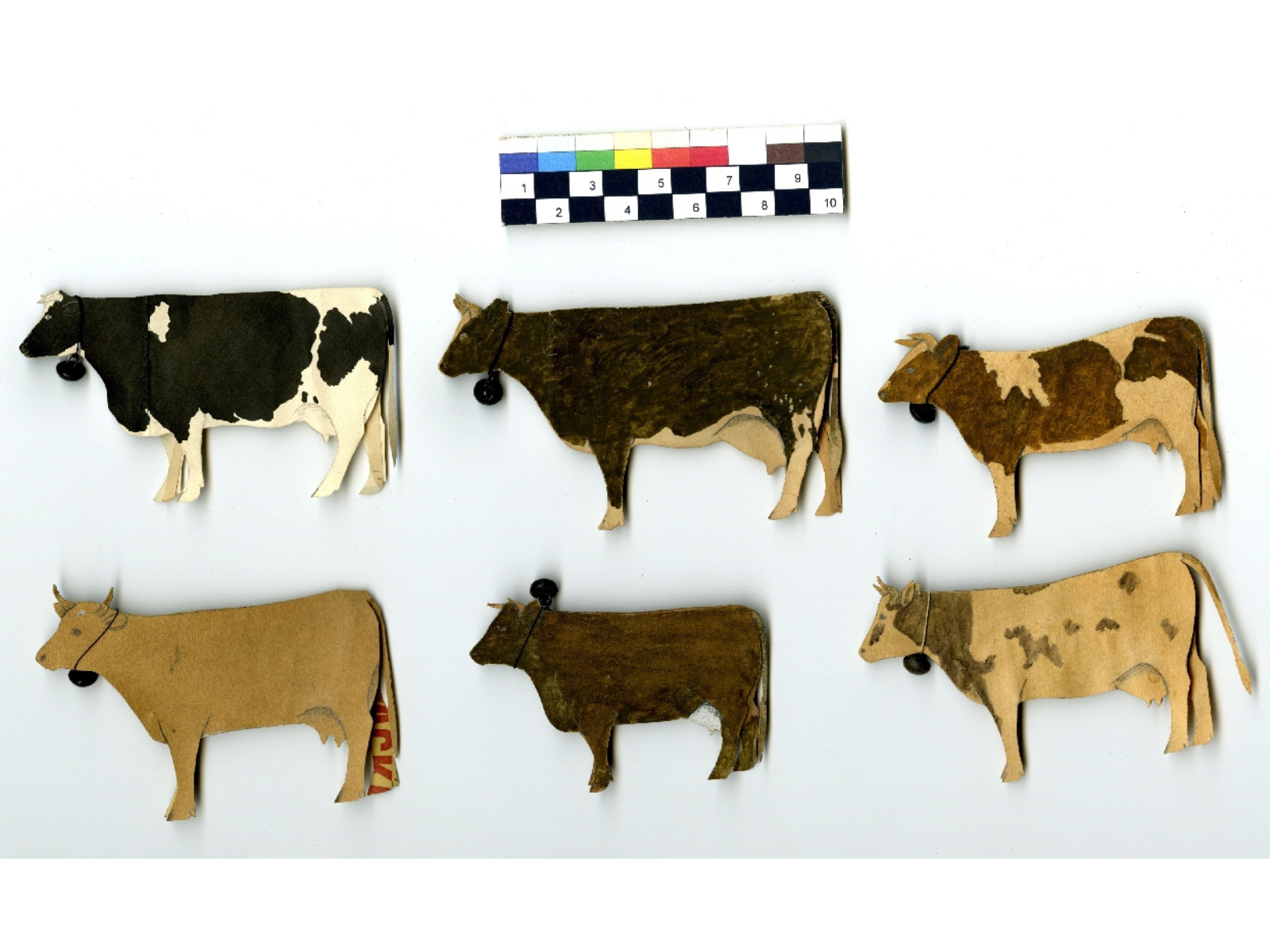

One of the lesser known aspects of museum work involves the lending and borrowing of artifacts and specimens. This isn’t to say you can borrow the Nonsuch for a lovely family sailing holiday, but other museums and heritage sites often work with us to make the most of our collections. Lower Fort Garry has several pieces of our HBC Museum Collection onsite to illustrate the rich history of the fur trade, for instance. Loans can be short little stints for special events or drag on for decades as the original paperwork yellows in its file folder. As I wrapped up cataloguing all of the Criddle collection, I realized that one remaining artifact had been on loan to the Sipiweske Museum since 1991. Other than a black and white photograph, we had no data on this object – a telescope used by Percy Criddle to observe Halley’s Comet in 1910– which meant…a ROAD TRIP!!!

All objects in our collection need to be catalogued and undergo a condition report, so your friendly neighbourhood cataloguer (me) and our conservator extraordinaire (Carolyn) headed off on an adventure towards the quiet, picturesque town of Wawanesa, 202 kilometres west of Winnipeg, to visit the elusive Criddle telescope.

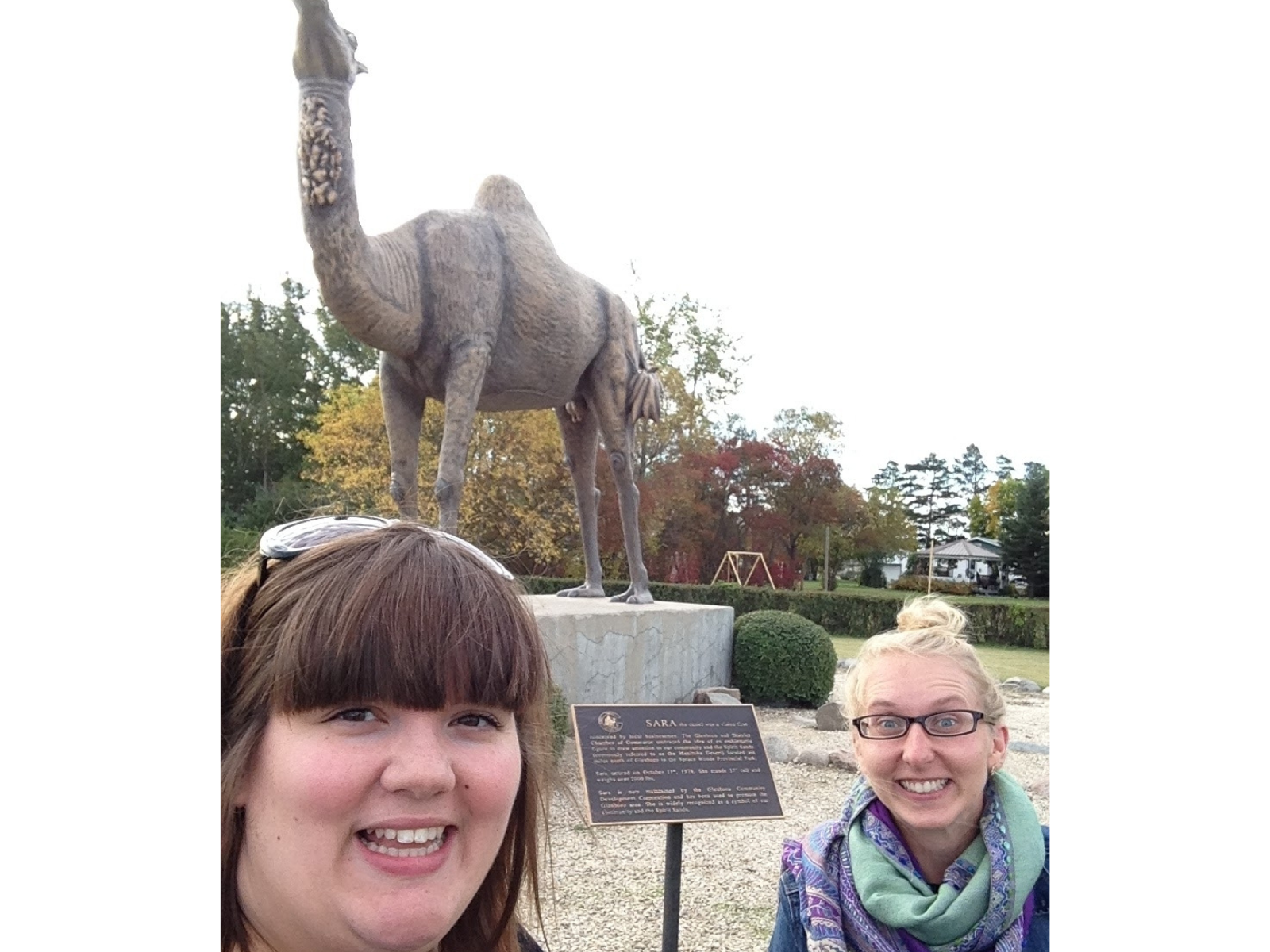

We were making good time, so I decided to show Carolyn some of my favourite stops along Highway 2, including the World’s Largest Smoking Pipe in St. Claude (my grandpa’s hometown!) and Sara the 17 foot tall Camel in Glenboro.

Arriving in Wawanesa, we headed to the Sipiweske Museum and made our way through the winding galleries until we arrived at the telescope. We wasted no time getting to work, examining the 130 year old telescope from every angle. This Browning telescope was made in London and brought over to Percy Criddle in 1885 by his friend and benefactor, J.A. Tulk.

Pulling apart the eyepieces, I found a lovely surprise – Percy Criddle’s name, written in his own hand inside a lens piece, preserved for all this time. He treasured this telescope and observed many celestial events with it, including the passing of Halley’s Comet and a lunar eclipse.

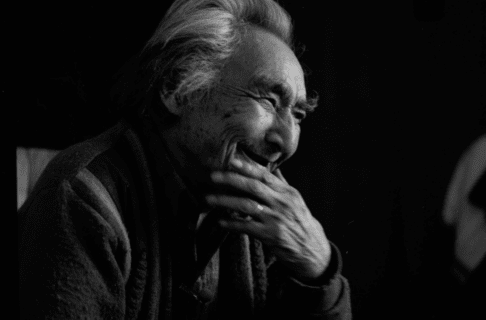

After all the disassembling, measuring, describing, photographing, and reassembling, we celebrated with a telescope selfie, as you do.

Before heading back to Winnipeg, Carolyn and I decided to visit Aweme (now the Criddle/Vane Homestead Provincial Heritage Park), the homestead of the Criddles from 1882 to 1960. Sadly, the big house, St. Albans, was destroyed by fire in June 2014. We poked around the sandy patch where the house once stood, trying to picture it.

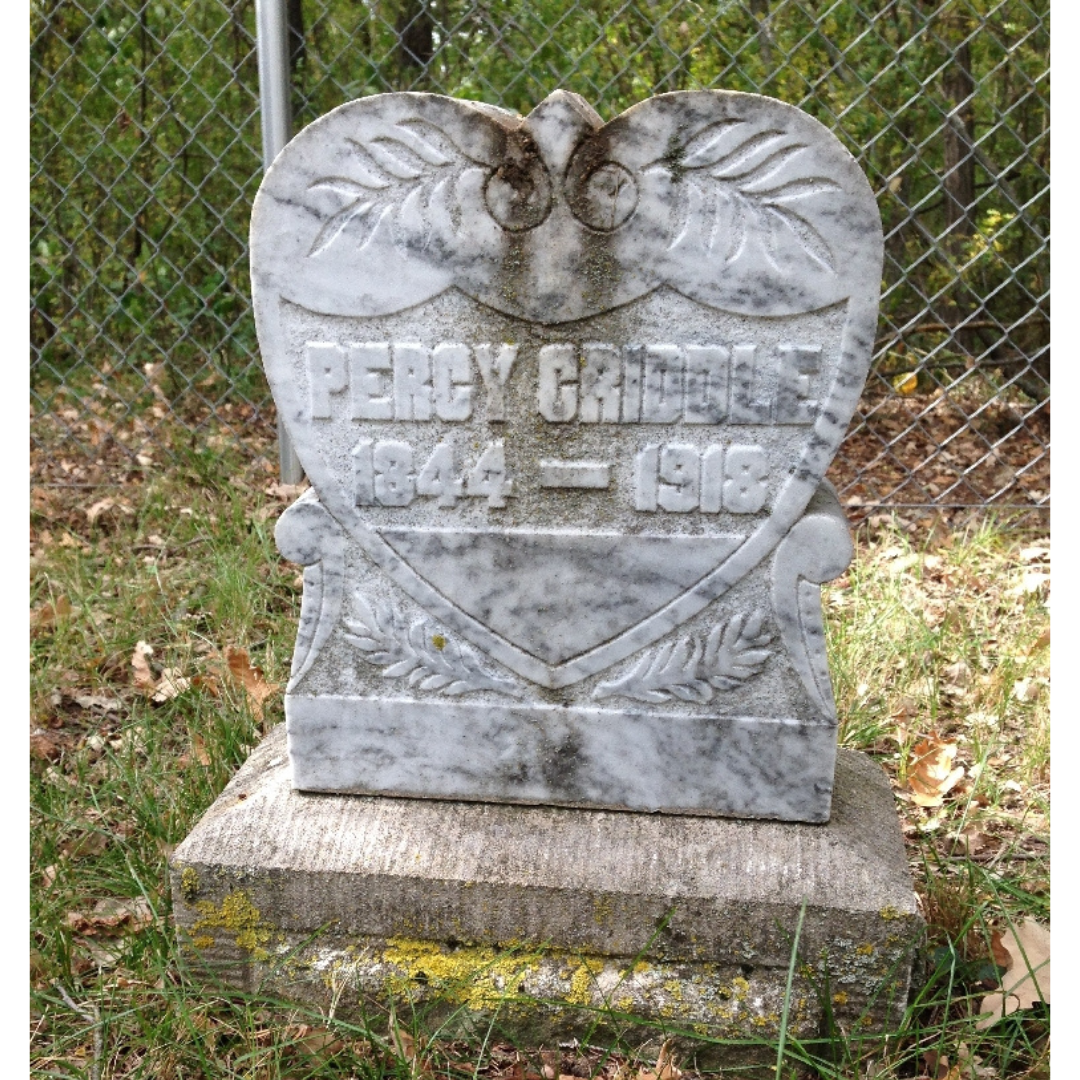

We hiked around the short trail, exploring Norman Criddle’s entomology lab and the crumbling foundation of Stuart Criddle’s former home, Gardenview, before stopping to pay our respects to Percy Criddle and his family at the graveyard.

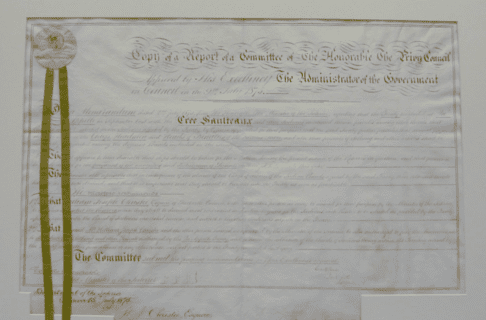

Percy’s telescope has been catalogued, all its information and history entered into the collections database, the loan renewed for a five year term. Head out to Wawanesa and see it for yourself!