Posted on: Wednesday October 28, 2015

With the potential legalization of recreational marijuana in Canada in the news, it is useful to know a little bit about the history of this unusual plant. So here is my list of things you (probably) didn’t know about marijuana aka Cannabis.

1. Marijuana and hemp are the same species.

Technically both these plants belong to the same species: Cannabis sativa. However, industrial hemp is a cultivar that has been bred to produce good fibre while marijuana has been bred to maximize its tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content. Hemp has little to no THC in it.

2. Cannabis sativa means “cultivated fragrant cane”.

Cannabis sativa is the scientific name of the plant. All species have a genus (Cannabis ) and a species epithet (sativa ). The name is derived from the ancient Greek word for the plant (kannabis ) which means “fragrant cane”. The term “sativa” means “cultivated” in Latin.

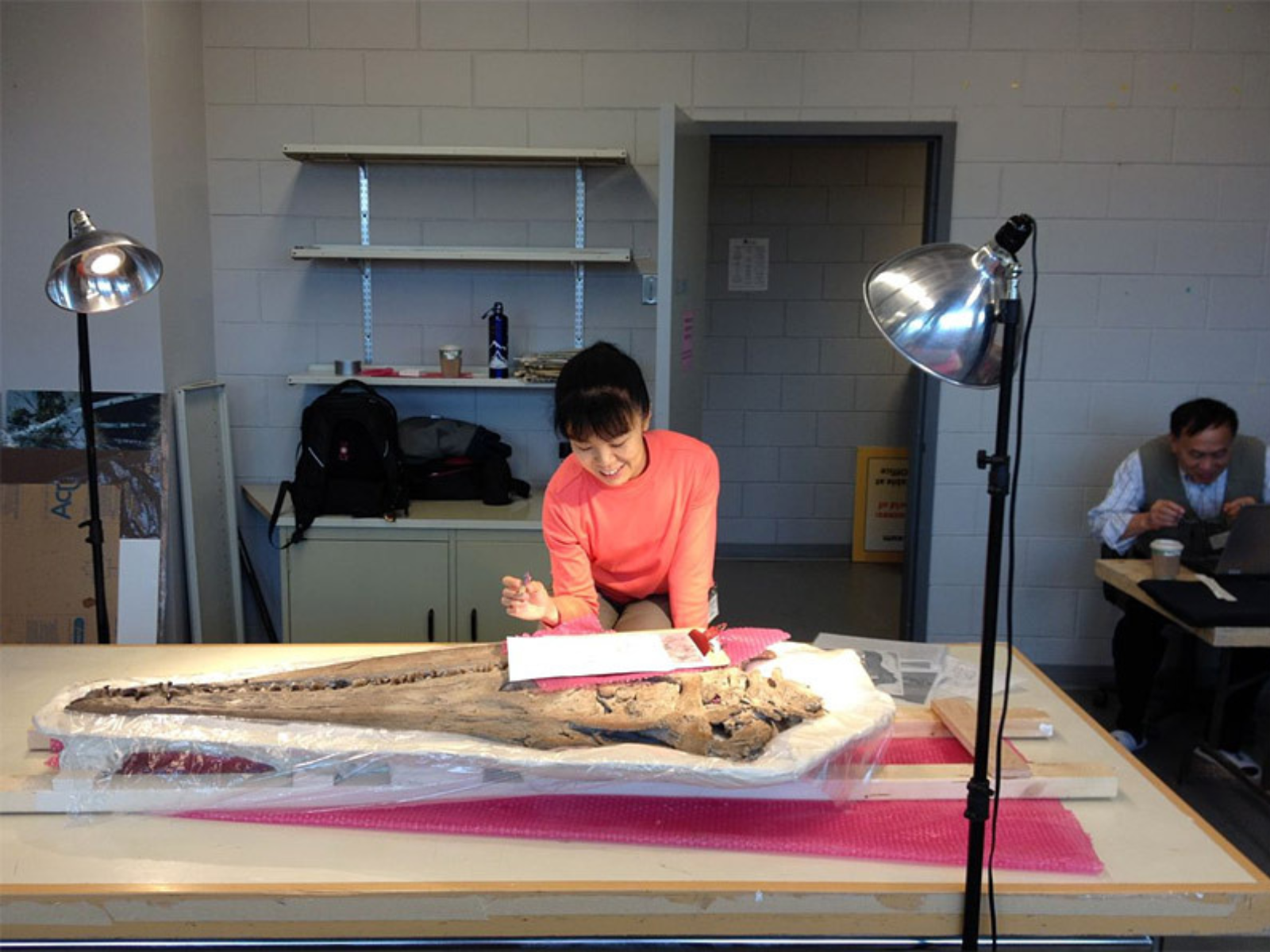

Image: A display drawer in the Parklands/Mixedwoods Gallery shows rope made from natural fibers like wood nettle (Laportea canadensis) and hemp dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum).

3. Cannabis was once thought to grow in the wilds of Canada.

The explorer Jacques Cartier reported seeing “wilde hempe” in Canada. However, he was probably referring to hemp dogbane (Apocynum cannabinum) or wood nettle (Laportea canadensis), species traditionally used by First Nations peoples for rope making. Cannabis is actually native to China, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tagikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

4. Canadians were legally required to grow Cannabis at one time.

In the 1600-1700’s, Nova Scotian and Canadian (Quebec) farmers were required to grow hemp as Briton and France needed it for ship building; up to 80 tons of hemp were needed for every ship. However, many farmers did not want to grow hemp as they preferred growing food so they wouldn’t starve. King James I made the cultivation of hemp and flax mandatory in the English colonies of North America in 1611. In Quebec, King Louis XIV’s representative Jean Talon seized all of the thread that was for sale and distributed it only to farmers in exchange for hemp, so desperate were they to get their hands on some for their shipbuilding industry.

Image: Wood nettle, sometimes called hemp nettle (Laportea canadensis was traditionally used for rope making in Canada.

5. It was legal to grow Cannabis during World War II.

In 1938 growing any Cannabis sativa (even hemp) in Canada was outlawed. During World War II the ban on hemp was lifted because the fibre was needed for the war effort as Japan controlled much of the land where hemp was being grown. The commercial growth of industrial hemp in Canada finally became legal again in 1998, although a licence is required for any farmer who wishes to do so. In 2015 the sale of hemp for its fibre, oil and seeds are projected to make Canadian farmers $45-$85 million.

6. Beer contains a close relative of Cannabis.

Hops or Humulus lupulus is in the same plant family as Cannabis : the Cannabaceae. Hops, which any beer aficionado knows, are the crucial ingredient to a good beer. The flowers of hop plants are covered with fragrant resin just as Cannabis flowers are. These flowers impart a bitter flavour to beers, as well as helping to preserve the brew.

Image: Hops (Humulus lupulus), a key ingredient in beer, grows wild in Manitoba. TMM B-4621.

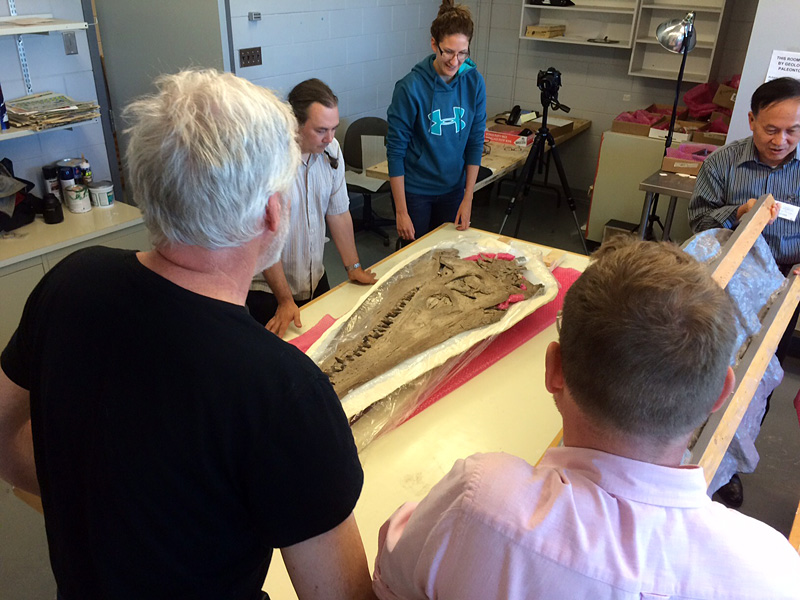

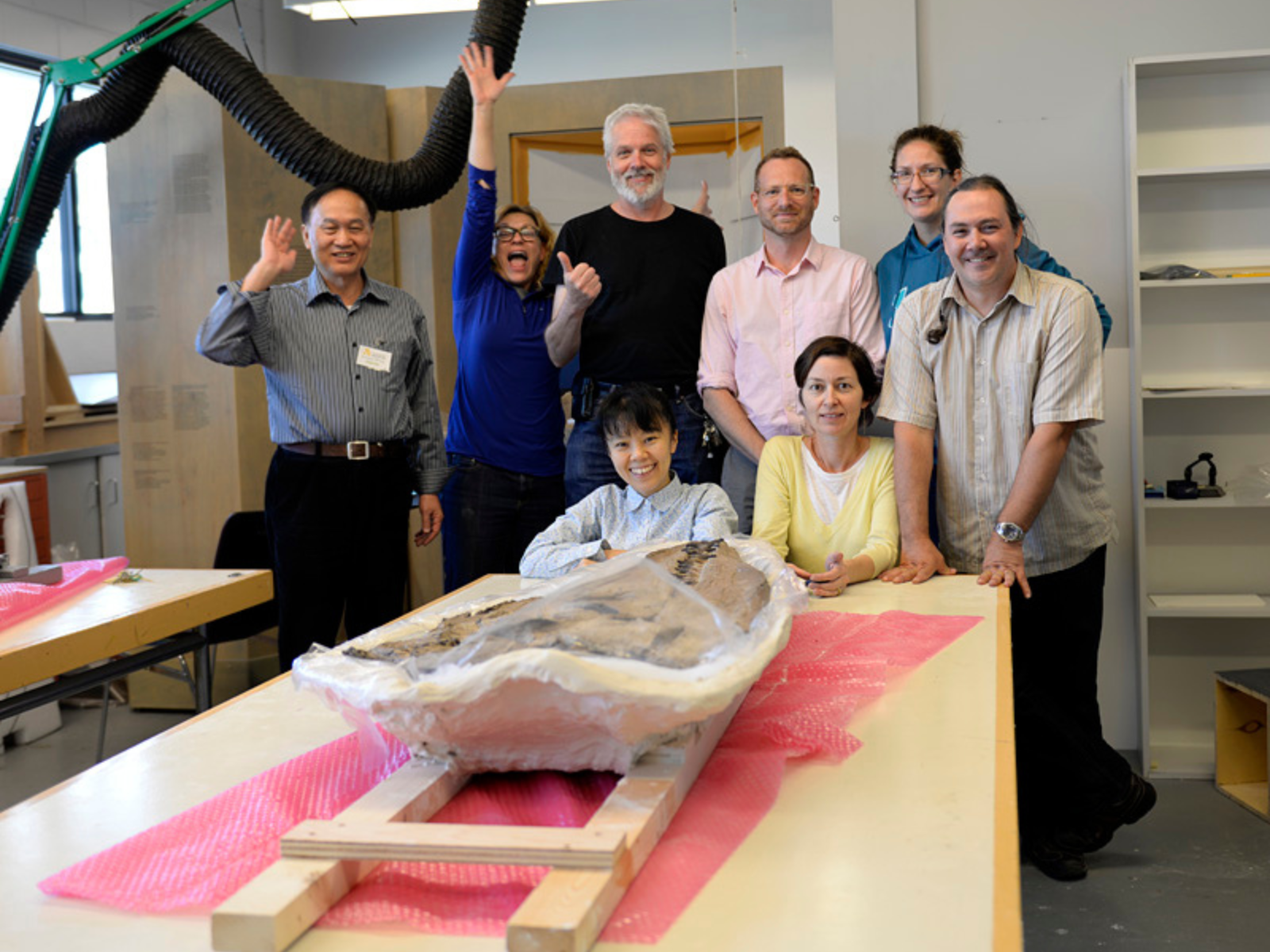

7. Cannabis is on display at The Manitoba Museum.

Cannabis can be seen in the Nonsuch Gallery; all of the ropes on the Nonsuch are made of hemp. Further, the ‘oakum’ used for caulking the joints between the boards was made from hemp fibres and Stockholm tar, which is what gives the ship that smoky smell. The Museum also has 15 hempen artifacts in the history collection (mainly textiles).

All of the ropes on the Nonsuch are made of hemp.

The Museum’s collection of textiles includes some hempen rugs. These artifacts are stored behind the scenes in the Museum’s vault.