Posted on: Thursday November 27, 2014

By Dr. Graham Young, past Curator of Palaeontology & Geology

In my last blog post, introducing our plesiosaur exhibit, I promised to follow up with some of the story of how the collectors found, extracted, and prepared the fossils. When I was assembling the exhibit I interviewed Kevin Conlin and Wayne Buckley, since they tell these stories so much better than I ever could. Here are the interviews, which are also on the panels within the exhibit.

Kevin Conlin

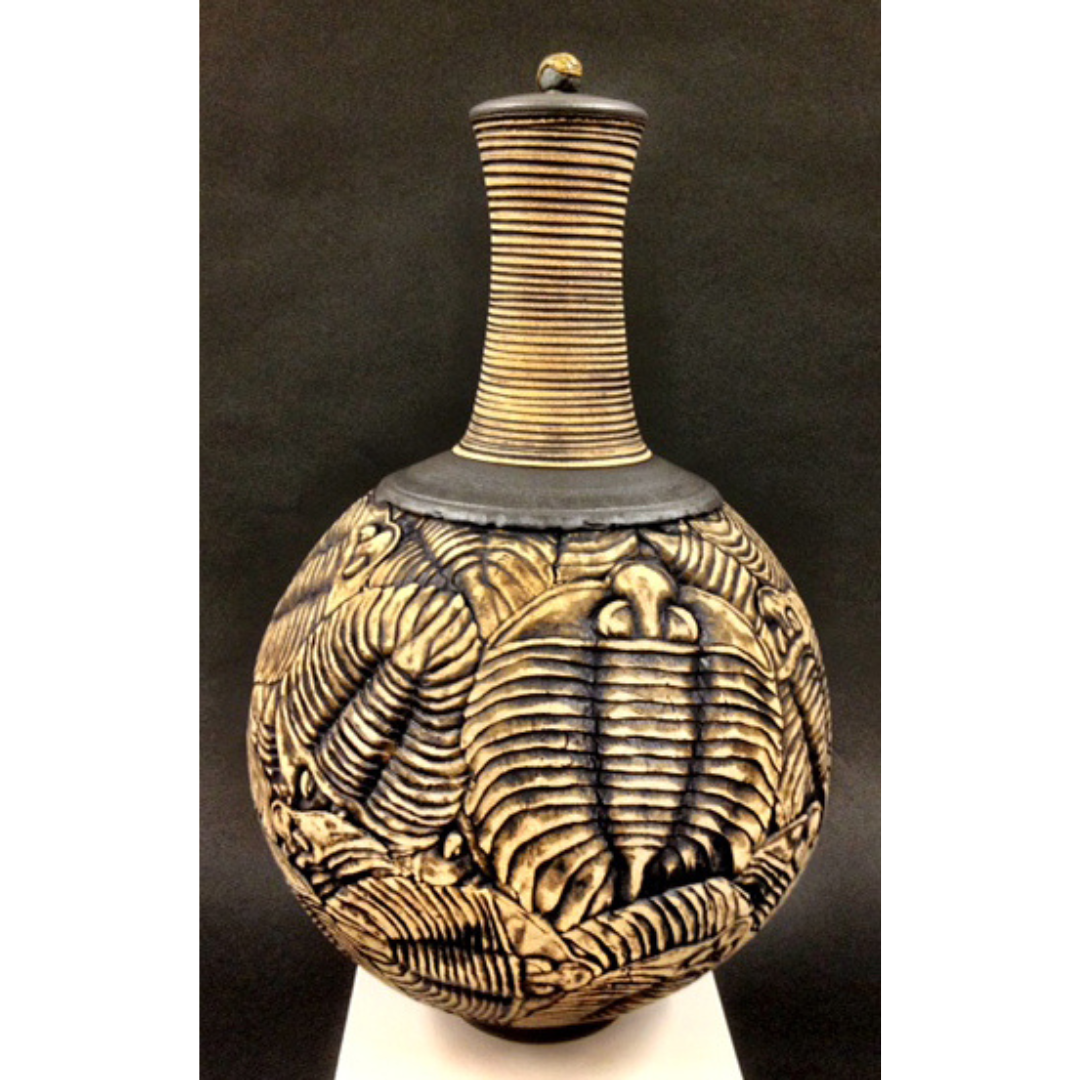

Kevin Conlin is a ceramic artist in western Manitoba who has worked with various museums, collecting and participating in scientific research. He collects fossils under permits from the Manitoba Historic Resources Branch, and has collected significant specimens now in the collections of The Manitoba Museum.

How did you get into fossil collecting?

It goes back to Grade 3, on a school trip to the Manitoba Museum of Man and Nature. I took my lunch money and purchased three trilobites from the gift shop. From there, I began to look into what fossils were, and started a long life of keeping my head down whenever I was out where there were rocks or gravels that could contain fossil material.

How do you find the fossils?

When I first got into collecting I didn’t know much about rock types. After taking some geology in school and university I began to recognize and distinguish rocks that would house fossils – the types of sediments or fossils in the area really dictate how you find fossils. I look for the odd shapes, textures, any variations in the surface of matrix or sediment which could indicate something other than just mud, sand or sedimentary rock. It could be anything from a pin prick to the size of a 200-pound boulder!

What do you do to prepare the fossils?

Depending on the fossil and its fragility, I use a special glue. For cleaning and preparing fossils, miniature jackhammers and a miniature sandblasting unit are used to remove sediment. It all depends on the fragility. Some fossils come naturally cleaned by the elements. Others still encased in rock can take hundreds of hours of preparation.

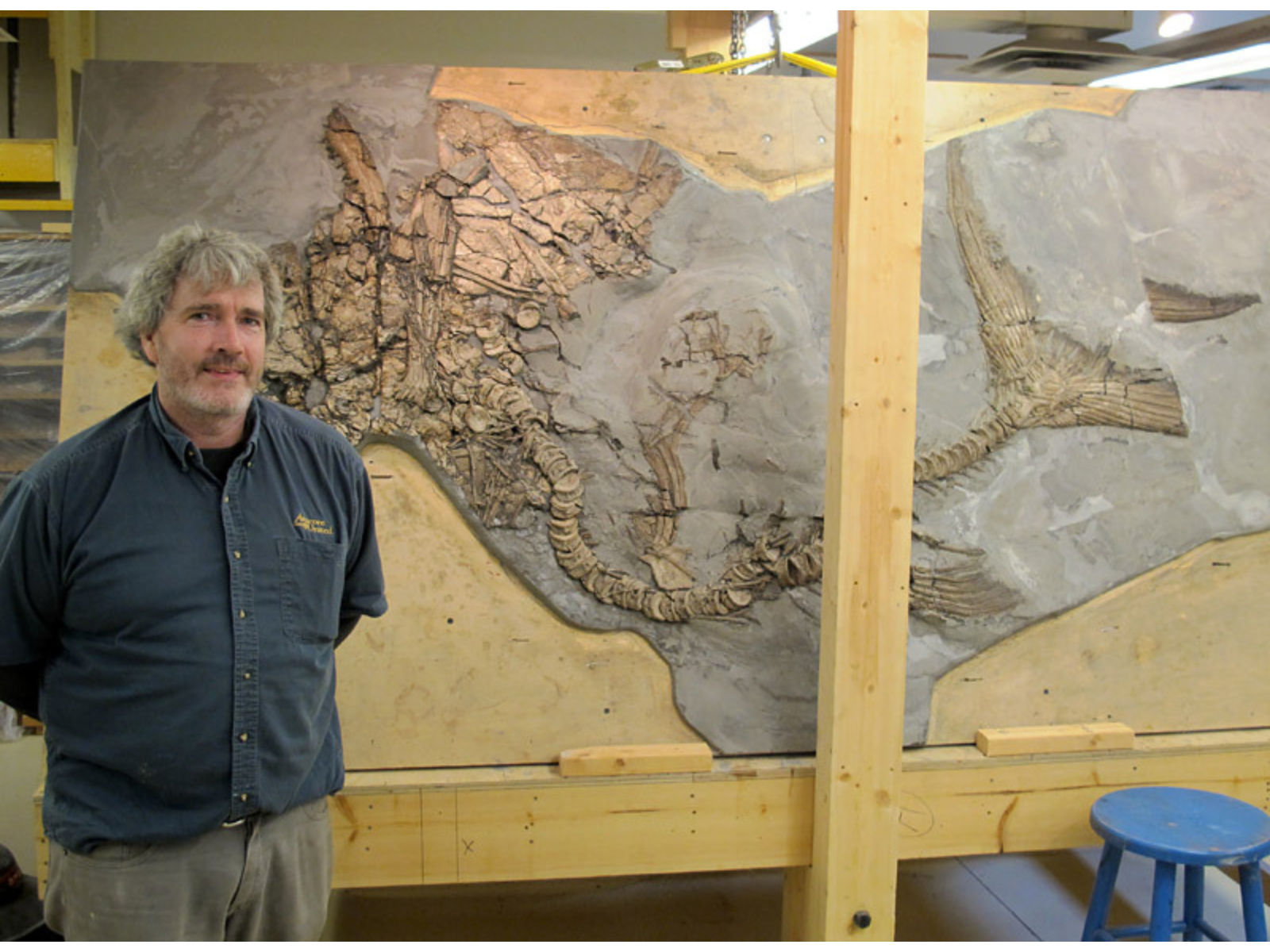

Kevin poses in Brandon with a large fossil fish that he is preparing.

Kevin creating ceramics in his studio (photo courtesy of Kevin Conlin)

Among the fossils you have found so far, which one is your favourite?

I like all fossils. They all bring great enjoyment – trilobites, birds, a Carboniferous collection that I really enjoy. I have no real favourites.

What do you think is the most pleasurable part of fossil collecting?

The most pleasurable part of fossil collecting to me is relaxation. Even though the work can be difficult, finding the fossil and knowing that you are the first human to see it brings a great deal of pleasure.

Why do you collect fossils? Why is it important to do this?

I collect fossils for the mystical quality from ancient worlds and the beauty they project. I also collect fossils for the purpose of preservation. It is important to preserve this material because nature will destroy it over time through erosion. Being a ceramic artist, a large part of my fossil collecting becomes an inspiration for my work. The interesting thing about being a clay artist is that many fossils are found in clay!

Wayne Buckley

Wayne Buckley is a retired agricultural research scientist in western Manitoba. He collects fossils under permits from the Manitoba Historic Resources Branch and has donated significant specimens to The Manitoba Museum.

How did you get into fossil collecting?

As kids, my cousin and I had an interest in collecting rocks. We had heard that you might be able to find fossils at a place we were camping, so we went looking and we found this beautiful ammonite. I remember being struck that it was possible for someone like me to find beautiful and interesting things like that. I was hooked for life!

What do you have to do to pull out a fossil you have found? What sorts of tools do you use?

I suppose the most important tool is a shovel; we do a lot of digging! Then we get the picks and crowbars to lever out big chunks of shale. As we get further into the rock it becomes quite hard, and I use a small jackhammer. Once the fossil is exposed, we need to prepare a trench around it, then cover it with a burlap and plaster cast. We’ve used various techniques to get fossils out of the bush. Early on it was mainly inner tubes with a piece of plywood – we would drag and float it out. Later I made a skid that would float and we could haul that behind an Argo (an amphibious vehicle).

Among all the fossils you have found so far, which one is your favourite?

That’s easy. That plesiosaur that I just donated [to the Museum] is certainly my favourite.

What do you think is the most pleasurable part of fossil collecting?

Well, I guess there are really two things that come to mind. First of all, there’s the thrill of making a discovery. That, however, is fairly rare. Probably just as important is that I enjoy being out in the bush. I really enjoy the relaxation that comes with eating my lunch on a vantage point, listening to the silence and watching the birds and other animals.

Dragging a field jacket with the Argo. (photo courtesy of Wayne Buckley).

Wayne preparing the plesiosaur skull (photo courtesy of Wayne Buckley).

Wayne with a large fossil fish (Ichthyodectes sp.) that he collected and prepared. This fish is featured in our current exhibit.

What sorts of sources do you use to identify the fossils?

There’s a great website called Oceans of Kansas. It describes many of the fossils that we find in Manitoba, because they are also found in Kansas. Also, as I have a background in science, I am quite comfortable with searching the scientific literature and ultimately going to the original research papers where new species were named.

Why do you collect fossils? Why is it important to do this?

I have a passion for fossils. I think collecting them is important because we don’t have a complete record of the early life that was in Manitoba during the Cretaceous Period. I feel that we are able to make significant scientific contributions. It’s also important to save the fossils; erosion is very rapid where we are collecting and fossils simply erode away.

Image: Wayne in the fossil quarry he created during collection of the plesiosaur (photo courtesy of Wayne Buckley).