Posted on: Wednesday March 19, 2025

Geologic time is truly staggering. It is hard to comprehend even for geologists, so we often rely on analogies to convey the vastness of time. If you could count one year per second, it would take an hour and 17 minutes until you had counted the age of the oldest Egyptian pyramids. Keep going, and it would take over 2 years before you reached the end of the age of dinosaurs. You would have to keep going for another 5 and a half years to get to the age of the earliest dinosaurs and another 12 on top of that to reach the earliest animals. It would be impossible to count to the age of the Earth, as it would take 144 years to get to 4.54 billion.

But, how do we actually know how old a particular specimen or event is? This is one of the most common questions I am asked as Curator of Palaeontology and Geology. It’s an excellent question, but not an easy one to answer in a concise way, so I will do my best to provide a more comprehensive answer here.

Manitoba has changed immensely over Earth’s history. While Churchill is now a cold, arctic environment close to 60 degrees north of the equator, about 450 million years ago it was equatorial and covered by a tropical sea. This is due to the shifting of the plates that make up the Earth’s crust, which move at about the speed that your fingernails grow.

Rocks and Clocks

You may have heard of carbon dating before. This approach relies on the radioactive decay of a naturally occurring form of the chemical element carbon. As with all elements, carbon atoms can come in several different forms, called isotopes. Isotopes share the same number of positive particles (protons) in their atomic nucleus, but differ in the number of neutral particles (neutrons). The majority of carbon on Earth is an isotope called carbon-12, which is stable. However, other forms of carbon exist, including an unstable form called carbon-14, characterized by two extra neutrons in its nucleus. Carbon-14 atoms decay over time, as one of their neutrons converts into a proton, releasing radiation and transforming the unstable carbon atom into a stable nitrogen atom. New carbon-14 is constantly being generated in the atmosphere by the action of cosmic rays from space which cause the conversion of nitrogen atoms into carbon-14.

Critically, the decay of carbon-14 happens at a predictable rate. By measuring this rate, we can predict that half of the carbon-14 that exists now will have decayed in 5,730 plus or minus 40 years. This length of time is known as the half life of carbon-14 and it is this concept that allows us to date materials made of carbon. Living organisms take in carbon, including carbon-14, either from carbon dioxide gas via photosynthesis or from feeding on other organisms. While organisms are alive, their supply of carbon-14 is continuously replenished. Once they die, carbon intake ceases and the carbon-14 “clock” is started. By measuring the amount of carbon-14 remaining in a sample of an ancient organism, we can calculate how long ago it died.

One of the oldest rocks on the surface of the Earth, called Acasta Gneiss, on display in the Earth History gallery. It is close to 4 billion years old and is found in Northwest Territories. The age of the Earth and Solar System are estimated to be even older based on measuring the age of meteorites and samples from the moon, which are less subject to processes that reset the radiometric “clock”.

Unfortunately, there’s a catch: if a sample is more than about 50,000 years old, the amount of carbon-14 remaining will be too small to permit an accurate age estimate. For older samples, scientists have to rely on different elements. For example, uranium-238 decays into lead-206 with a half life of about 4.47 billion years. Since uranium-238 is commonly trapped in in certain minerals when they form, it is ideal for measuring the age of older events in Earth’s history. Several other clocks, or more technically radiometric dating systems, exist and these can often be compared to each other to improve the accuracy of estimates.

Absolute and relative time

Not every sample can be dated using an absolute method. For example, many fossils are too old for carbon dating and have insufficient uranium content for uranium-lead dating (although new approaches are pushing the boundaries of what is possible).

Similarly, sedimentary rocks like sandstones and limestones are formed of many different components including fragments of older rocks, fossils, and mineral crystals that have grown in between. Dating these components can give differing ages, sometimes producing misleading age estimates for samples. Further, alteration of rock under high heat and pressure or by the seeping of groundwater can enable atoms to move into and out of its crystalline structure (element mobility), which can “reset” the radiometric system.

This is where a second, complimentary approach called relative dating comes in. Even before there was a well-developed conception of evolution, scientists noticed that there was a regular pattern to the occurrence of different species throughout Earth’s rock record. We now know that this pattern is a consequence of the evolution and extinction of species. Mammoths, dinosaurs, and trilobites are all found only in particular rock layers and are absent from others. At a finer scale, careful examination reveals multiple successions of particular species, from which a comprehensive sequence can be built up. Since rock layers are deposited one on top of the other, the ordered succession of organisms gives us a clue about the relative age of the layers they are found in. If we can date rock layers above and below a particular fossil using radiometric dating, then we know that the fossil must be intermediate between those ages. If we then find the same fossil elsewhere, we have a relative idea of how old the rock it occurs in must be.

This section of rock on display in the Earth History Gallery is the boundary between the Cretaceous and Paleogene Periods, marking the end of the age of dinosaurs. Radiometric dating has allowed precise age estimates for this boundary layer, recently placing it at 66.02 plus or minus 0.08 million years.

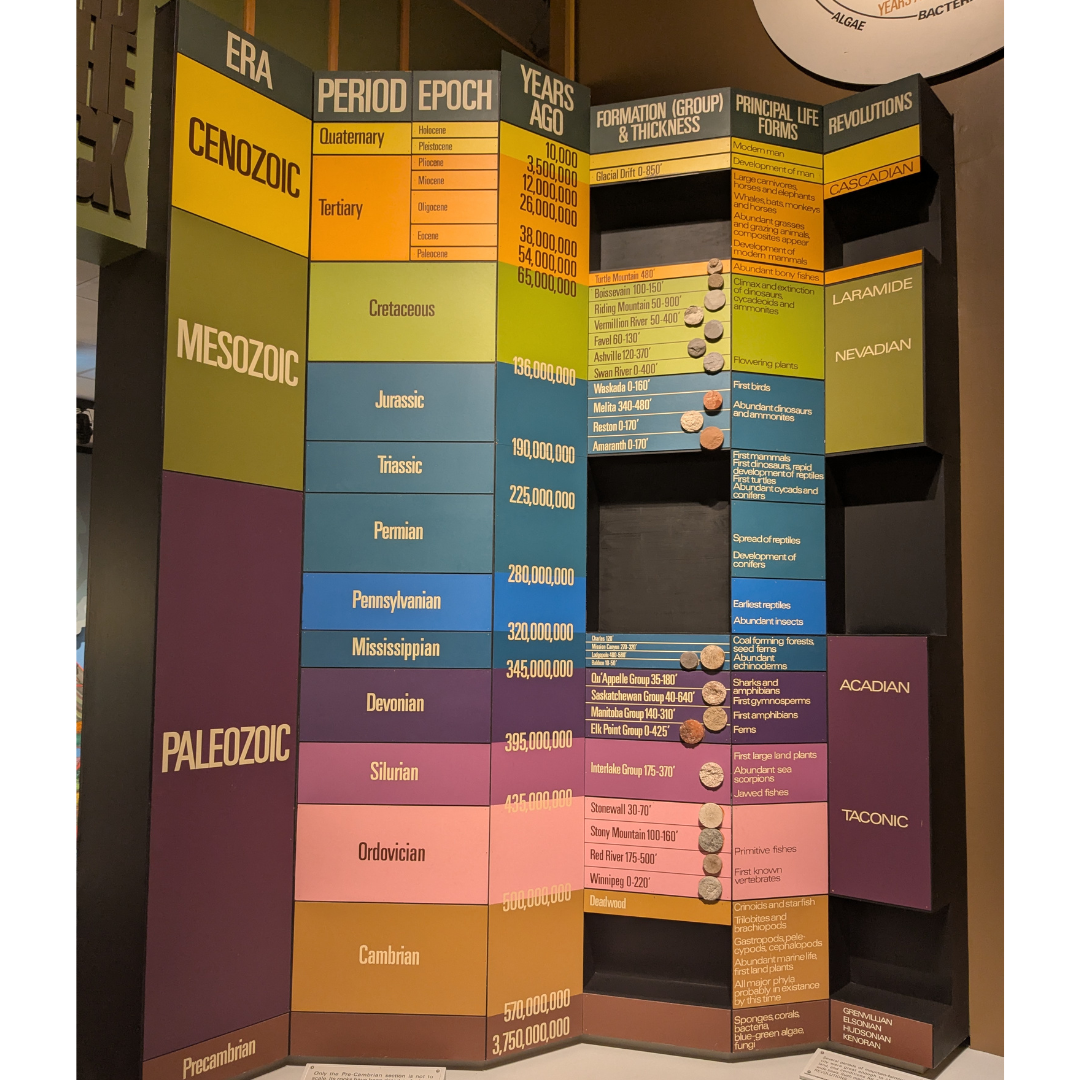

The time scale in the Earth History gallery shows the names of major time intervals. The cylindrical rock slices are pieces of rocks of each interval found in Manitoba. Some time intervals are not represented in our province, corresponding to gaps in the time scale. Since this display was constructed, there have been changes and refinements to the time scale that will require updating in the future.

Fossils are not the only source of information that can be used for relative dating. Chemical and magnetic signatures also exhibit observable patterns of change through time that can be used to order rock layers by age. By combining insights from various relative and absolute dating methods around the world, the Earth’s timescale has been built up. The timescale is broken up into a number of named intervals, often based on particularly noticeable changes in the types of fossils. For example, the end of the Cretaceous Period is marked by the extinction of the dinosaurs, with the exception of birds.

Earth’s geological time scale should certainly be ranked among our most significant scientific achievements. This is the result of a long and fascinating history, with insights being drawn from multiple different disciplines of study around the globe. While we now have a pretty good idea of the age of key events throughout Earth’s history, new research is constantly refining dates, enabling us to understand events in the deep past with ever increasing precision.