When most people think of plants, they typically picture flowers: cherry trees in bloom, colourful tulips and exotic-looking orchids. This is because 90% of all living plant species are flowering plants (i.e., angiosperms). But when dinosaurs first evolved 225 million years ago (mya), flowers were nowhere to be found.

First Plants

The first land plants did not produce seeds; instead, they reproduced using spores. Like amphibians, they needed water for reproduction, which restricted them to habitats that were moist. These spore-producing plants included mosses, liverworts, club mosses, horsetails, ferns and several, completely extinct plant groups called Rhyniophytes and Zosterophylls. When the first dinosaurs evolved in the Triassic Period (252-201 mya), spore-producing plants, like tree ferns and human-sized quillworts (e.g. Pleuromeia), were common (Palmer et al. 2009). Although these sorts of plants still exist today, their ancestors looked much different than the ones we are familiar with.

Tree ferns, like this one at the Montreal Botanical Garden, were common when dinosaurs still existed. © Manitoba Museum

The tiny Prickly Tree Club-moss (Lycopodium dendroideum), which lives on Manitoba’s forest floors, is one of the few surviving club-moss species. © Manitoba Museum

Ancient Seeds

Seed plants evolved in the Late Devonian (416-359 mya), eventually becoming the dominant vegetation by the Early Cretaceous (145-100 mya). A seed consists of a plant embryo, a source of food, and a protective coat. This adaptation helped seed plants, like conifers, gingkos and cycads, out-compete the spore-producing plants, particularly in drier habitats.

Modern Maidenhair trees (Ginkgo biloba) are considered “living fossils” because they look almost exactly like Jurassic fossils of ginkgos. From Wikimedia Commons.

First Flowers

Flowering plants similar to modern magnolias, dogwoods, and oaks, appeared rather abruptly in the fossil record, about 90 mya (Late Cretaceous). Decades of searching by palaeobotanists for the first flowers has finally borne fruit (pardon the pun). The most recent evidence of an undisputed flowering plant is a fossil named Florigerminis jurassica (Cui et al., 2021). The discovery of this fossilized flower bud and fruit, indicates that flowering plants evolved nearly 75 million years earlier than originally thought, in the Jurassic Period 164 mya (Cui et al., 2021).

Dinosaurs would have eaten cycads, plants that produce cones in the very centre of their trunk. This specimen was at the Montreal Botanical Garden. © Manitoba Museum

Floral Rarity

Part of the reason why flower fossils are so rare is because these structures are very delicate. Flowers likely decompose long before they can fossilize. In fact, some species that palaeontologists think were cone-bearing, may have actually borne flowers, since we only have fossils of their leaves. Another reason flowers did not often fossilize, is that Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous flowering plants may have grown in relatively dry habitats, where fossilization rarely occurs.

Most plant fossils consist of leaves or wood; flowers rarely fossilize. © Manitoba Museum B-254

Changing Ecosystems

It wasn’t just the animal world that changed when that giant asteroid hit the earth 66 mya; it was the plant world, too. In North America, about 50% of the plant species (mainly the slower-growing, cone-bearing plants) went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period (Condamine et al. 2020). Afterwards, the evolution of flowering plants was rapid, thanks in part to coevolution with pollinating insects like bees (Benton et al. 2022). With their quick growth, drought tolerance, and long-lived seeds, flowering plants were better able to colonize the devastated earth than cone-and spore-bearing species (Benton et al. 2022, Condamine et al. 2022). Thus, the evolution of flowering plants parallels that of mammals.

Above: Many modern flowering plants, such as Early Yellow Locoweed (Oxytropis campestris), coevolved with pollinating insects, such as bumblebees (Bombus). © Manitoba Museum

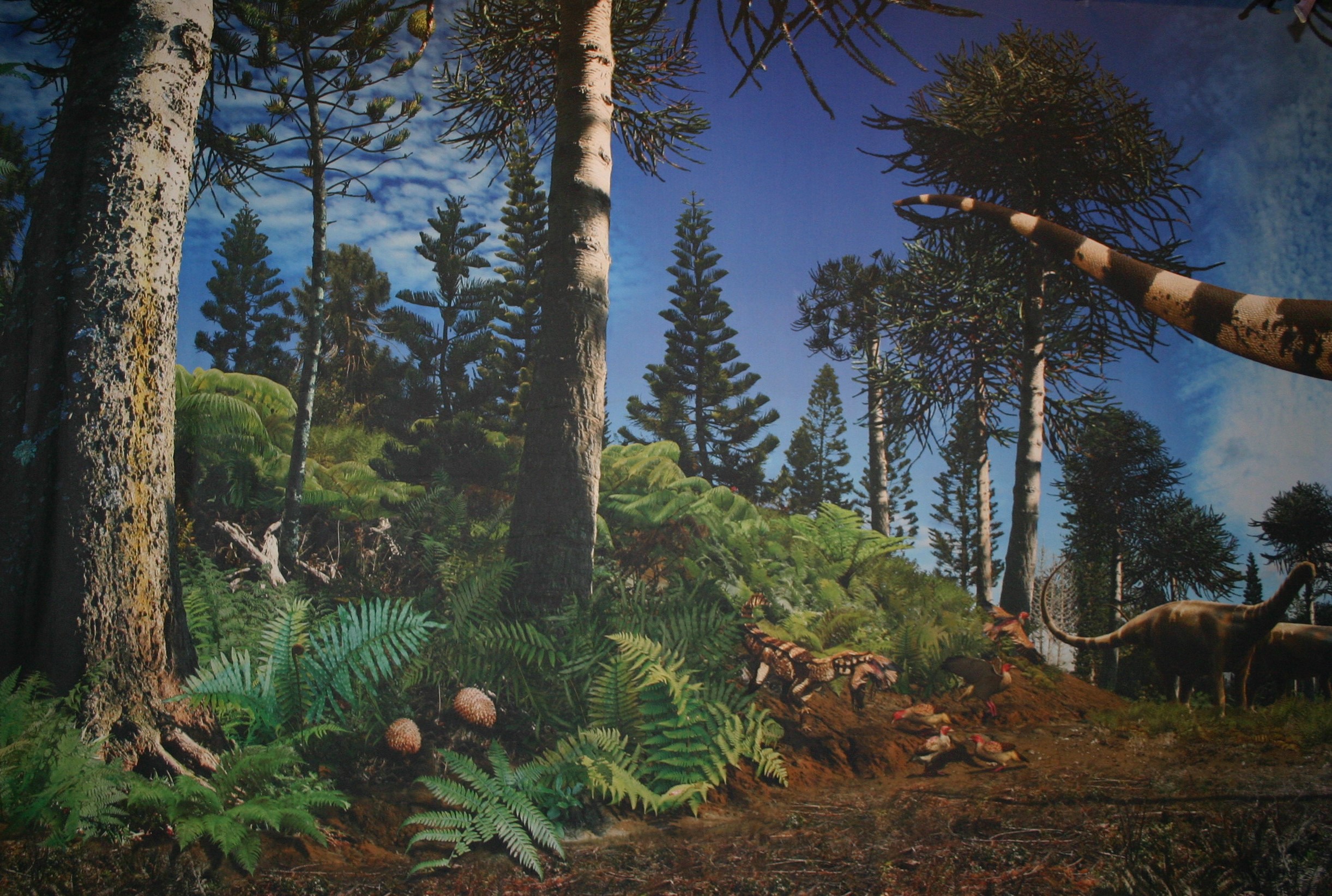

So, when you visit the Ultimate Dinosaurs exhibit at the Manitoba Museum during summer 2022, remember to look closely at the murals behind the dinos. They accurately portray the kinds of plants that supported those ancient creatures so long ago.

Mural art from the Ultimate Dinosaurs exhibit showing ancient vegetation communities. © Ultimate Dinosaurs Presented by Science Museum of Minnesota. Created and Produced by the Royal Ontario Museum. Mural Artist: Julius Csotoyi

References

Benton, M.J., Wilf, P. and Sauquet, H., 2022. The Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution and the origins of modern biodiversity. New Phytologist, 233(5), pp.2017-2035.

Condamine, F.L., Silvestro, D., Koppelhus, E.B. and Antonelli, A., 2020. The rise of angiosperms pushed conifers to decline during global cooling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(46), pp. 28867-28875.

Cui, D.F., Hou, Y., Yin, P. and Wang, X., 2021. A Jurassic flower bud from the Jurassic of China. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 521.

Palmer, D., Lamb, S., Gavira Guerrero, A. and Frances, P. 2009. Prehistoric life: the definitive visual history of life on earth. New York, N.Y., DK Pub.