Like many of you, I enjoy walking through my neighbourhood and smelling the sweet fragrances of the summer flowers. Unfortunately, like many things, flowers are ephemeral. When I see a flower, I am always reminded of the Robert Herrick poem urging us to:

“Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today,

Tomorrow will be dying.”

Since most wildflower field guides only feature pictures of the flowers and leaves, it is difficult, and sometimes impossible, to identify plants in the fruiting stage. So, to help our visitors identify the fruits of some of the most common plants in our province, a new case in the Museum’s foyer, called “The Importance of Being a Flower” recently opened. This case features 14 species of fruits juxtaposed with a photograph of the flower. Although fruits and seeds are not always attractive to look at, they are just as important as the flower, perhaps even more so, for they carry the DNA of another generation of plants in them. Flowers may only last a day, but seeds can last for decades or even centuries. The oldest seed to ever germinate was a 2,000 year old date palm collected by archaeologists in the 1960’s from a fortress that had been build by Herod around 35BC and destroyed by Romans in 73AD (click here to read more)!

A new, temporary exhibit on seeds is in the Museum’s foyer.

In severe drought years, like the one we are experiencing this year, some summer- and autumn-blooming perennial plants will not produce flowers or seeds at all; they conserve scarce water resources by foregoing reproduction altogether. Doing so increases the likelihood that the adult plants will survive. Although most spring-blooming plants did produce flowers, they may produce fewer seeds to reduce water stress on the adult plant.

Museums and other institutions like gene banks and University herbaria, protect and preserve fruits, seeds and other storage tissues of economically important species, as well as wildflowers. You may have heard of one of these facilities, the so-called “doomsday vault”, formally known as the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. This Norwegian facility has ultra-cold storage freezers that keep the DNA in seeds from degrading rapidly, the way they would at ambient temperatures. However, that facility is our last line of defence; other collections are also needed to adequately protect plant genetic diversity, including the Plant Gene Resource of Canada in Saskatoon, (click here to learn more). Many of our most important crop species are stored in gene banks for use in breeding programs, or to use if natural disasters negatively affect crop fields or wild plant populations.

The Museum collection contains the fruits and seeds of many species.

The fruits and seeds of each species are displayed on top of a picture of the flower. MM 45580

Museum designer Anastasiia Mavrina tests the specimen layout for the case.

Another important thing to remember is that plants are constantly evolving to adapt to new conditions. Therefore, it is important for botanical institutions to continue collecting new samples to capture this evolution. As well, seeds stored in the vaults must be periodically grown, to allow them to generate newer, fresher seeds for preservation.

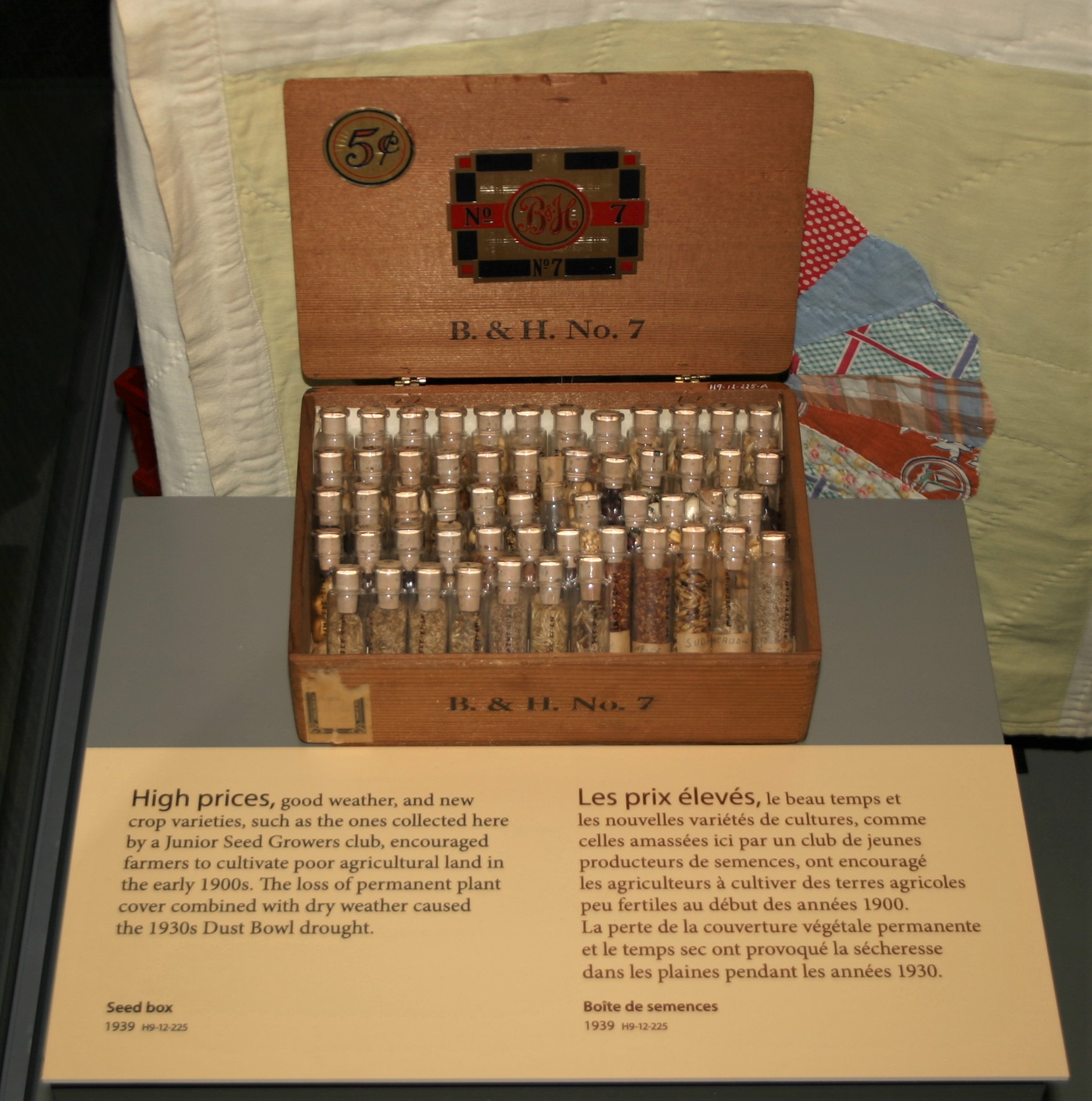

In addition to the foyer case, several of the Museum’s old seed collections are on display towards the end of the brand new, Prairies Gallery. Wildflower seeds collected in the 1920’s by naturalist Norman Criddle, are in the Breaking the Land case, and a collection of crop seeds made by a Junior Seed Growers Club in the 1930’s, are in a case on the Great Depression.

Some of the seeds in the Museum’s collection are so small that I marvel at the fact that all the information needed to build a new plant is actually inside. Life is truly amazing! Now, get out there and carpe diem!

This collection of crops seeds is in a case on the Great Depression in the new Prairies Gallery. H9-12-225

Norman Criddle collected the seeds of many species of wildflowers in the Carberry Sand Hills in the 1920’s. H9-23-142