Celebrating Canada’s first 150 years does not usually involve thinking about the environment or biodiversity, and certainly Confederation is a human history event. But human actions have an impact on our environment and the creation of Canada was no exception. Our latest exhibit, Legacies of Confederation: A New Look at Manitoba History, offers an opportunity to explore those impacts, those legacies, from a natural history perspective. Given the massive changes to Manitoba’s environment since 1867 (and 1870 when we became Canada’s fifth province), it is easy to focus on the negative effects; indeed, grasslands and many of their component parts have become rare or have even disappeared. But becoming a nation can also bring substantial resources to bear on mitigating those impacts through policy, funding, social conscience and national pride.

Outlaw #5 is a magnificent bison head that hung in the Winnipeg City Council Chambers in 1912 and is now hanging for all to see in the Legacies exhibit. This seems the beginning of a depressing story rather than a positive one, and in some ways it is; this bull bison is an unlucky representative of one of the last significant herds of plains bison (Bison bison bison) in North America at the turn of the 20th century. But it also represents the beginning of an incredibly successful conservation story – bringing bison back from the brink of extinction. I have introduced this specimen before, but this amazing mount has so many incredible stories to tell that I can’t resist an encore presentation.

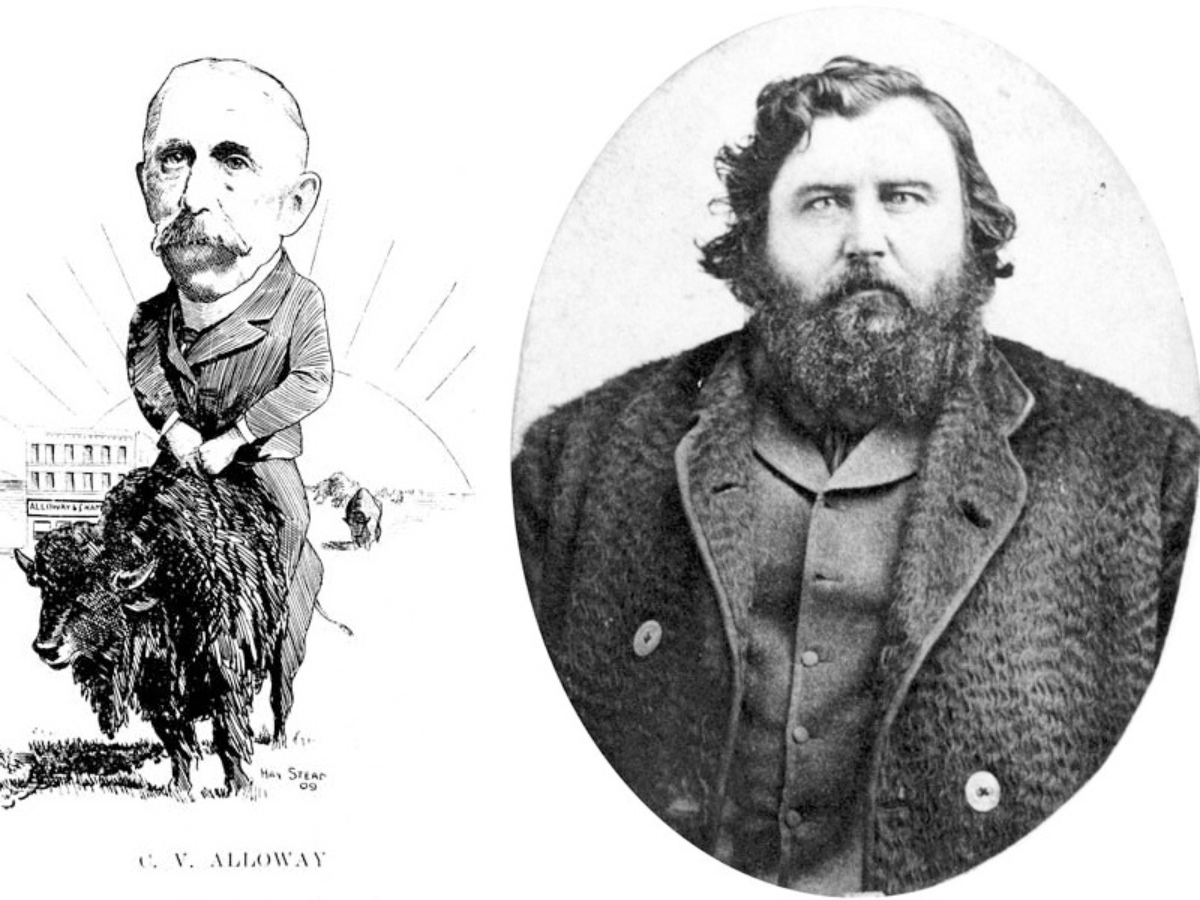

Caricature of Charles Alloway (Manitobans As We See ‘Em, 1909) and photo of James McKay (Archives of Manitoba), owners of a bison herd in Manitoba that, in part, found its way to the Pablo-Allard herd in Montana.

The big bull once roamed the grassy hills of Montana as part of the Pablo-Allard herd. Much of this herd, perhaps all, was made up of what were originally Canadian bison (although nationalities are irrelevant to the animals!). The initial herd was the offspring of a few calves brought from near the Alberta/Montana border in the early 1870s. Others arrived through a rather circuitous route, likely from calves caught near Prince Albert, Saskatchewan by Charles Alloway (brother of William Alloway, founder of the Winnipeg Foundation) and James McKay (Manitoban politician, Treaty negotiator) also in the early 1870s and kept at Deer Lodge in Winnipeg. These went to Stony Mountain Penitentiary under the care of Samuel Bedson (warden), becoming a herd of perhaps 100 over about ten years. Most of these were sold to Charles “Buffalo” Jones in the late 1880s and brought to Kansas before eventually becoming part of the Pablo-Allard herd in Montana through sale. Here the herd grew to several hundred, but Pablo (Allard had passed away) was notified by the U.S. government that his lands could no longer be used for bison. He offered them for sale to Washington but negotiations bogged down.

Canada came to the rescue. Alexander Ayotte, a Manitoban working for Canadian Immigration in Montana at that time, heard that the bison were up for sale and he notified Canadian officials. A deal was struck and Canada bought the herd in 1907. There is some suggestion that purchasing the Pablo-Allard herd was as much an opportunity for the government in Ottawa to poke a stick in the eye of the United States as it was to preserve a species, but there is little doubt that the individuals directly involved with the transfer, as well as the general public, were genuinely committed to conservation. Regardless, the end result was that over 700 bison were brought by train to Alberta, the nucleus of essentially all plains bison we see in Canada today and the basis of a conservation success story.

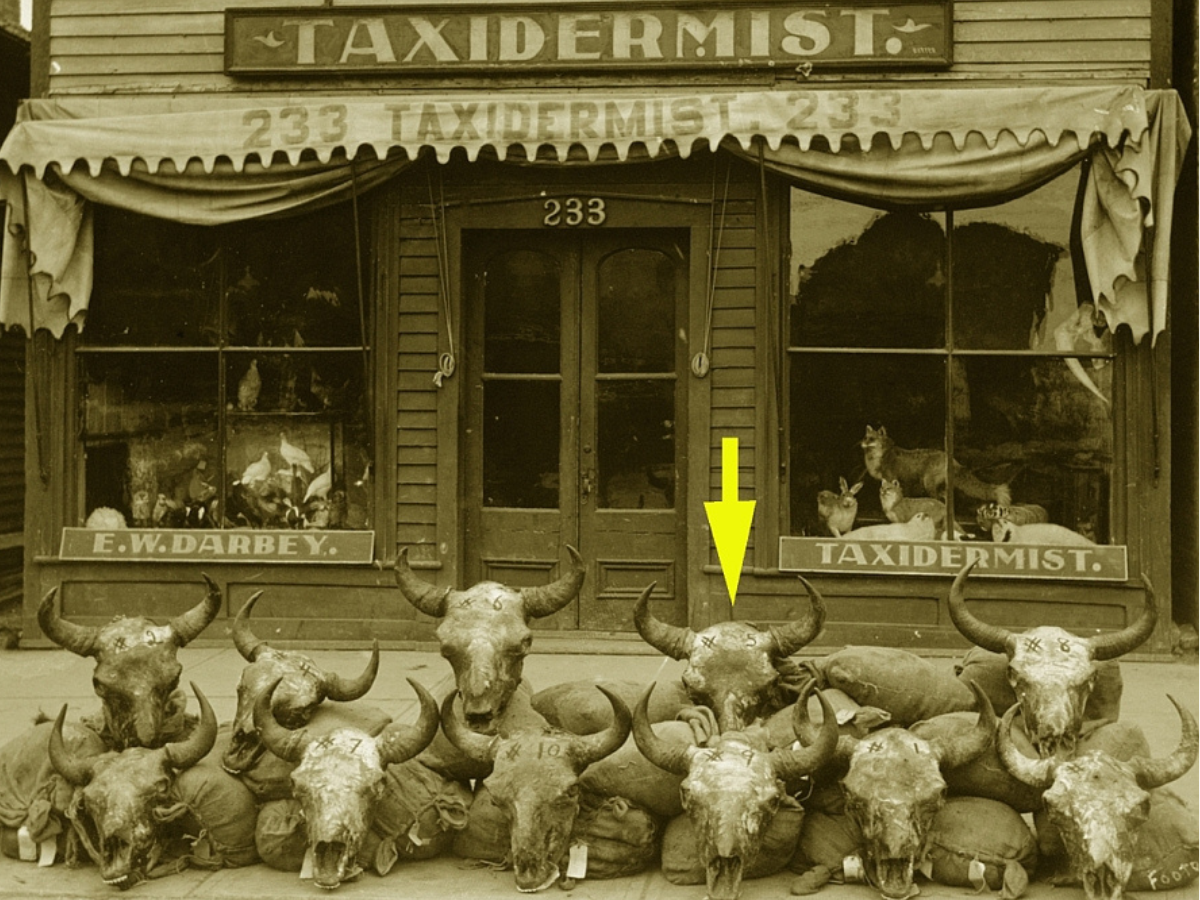

Finished bison heads on an outside wall in Winnipeg ready for auction in November 1911.

(Archives of Manitoba)

So where does Outlaw #5 fit in? As you might imagine, getting wild bison onto a train to Canada is no easy feat and some of them, the “outlaws”, refused to board. These remaining animals had no home and they were shot. At least thirteen outlaw bulls found their way to Winnipeg and into the skilled hands of Manitoba’s Official Taxidermist (yes, we had one of those), E. W. Darbey. He mounted these in his shop at 233 Main Street and they were auctioned in the fall of 1911.

E.W. Darbey’s shop on Main Street with bison skulls on the sidewalk in 1911. The yellow arrow points to skull #5, the Museum’s “outlaw” originally identified by the shape and patterns of the horn sheaths. (Archives of Manitoba)

As I noted in my original blog, I used the horn patterns from the archival photographs and those on the Museum specimen to identify it as #5, marked by the yellow arrow in the image above, a task that was none-too-easy or even certain. To prepare the specimen for exhibit, it required careful conservation to repair damage on the skin, nose, and ears, as well as stabilization of the backboard before we could hang it. Carolyn Sirett, our conservator, had to remove the backboard from the mount and the first thing she saw was that the mount was numbered. She immediately called me to say I should come up to her lab. To my relief (and some satisfaction), in large black writing was “No. 5”! Carolyn repaired the mount, and removed an incredible amount of dirt from the fur to make the specimen look much as it must have over 100 years ago.

Conservator Carolyn Sirett uncovered the “No. 5” beneath the backboard (at left) while repairing the mount for exhibit, confirming (thankfully!) my original identification from the Main Street photograph of skulls.

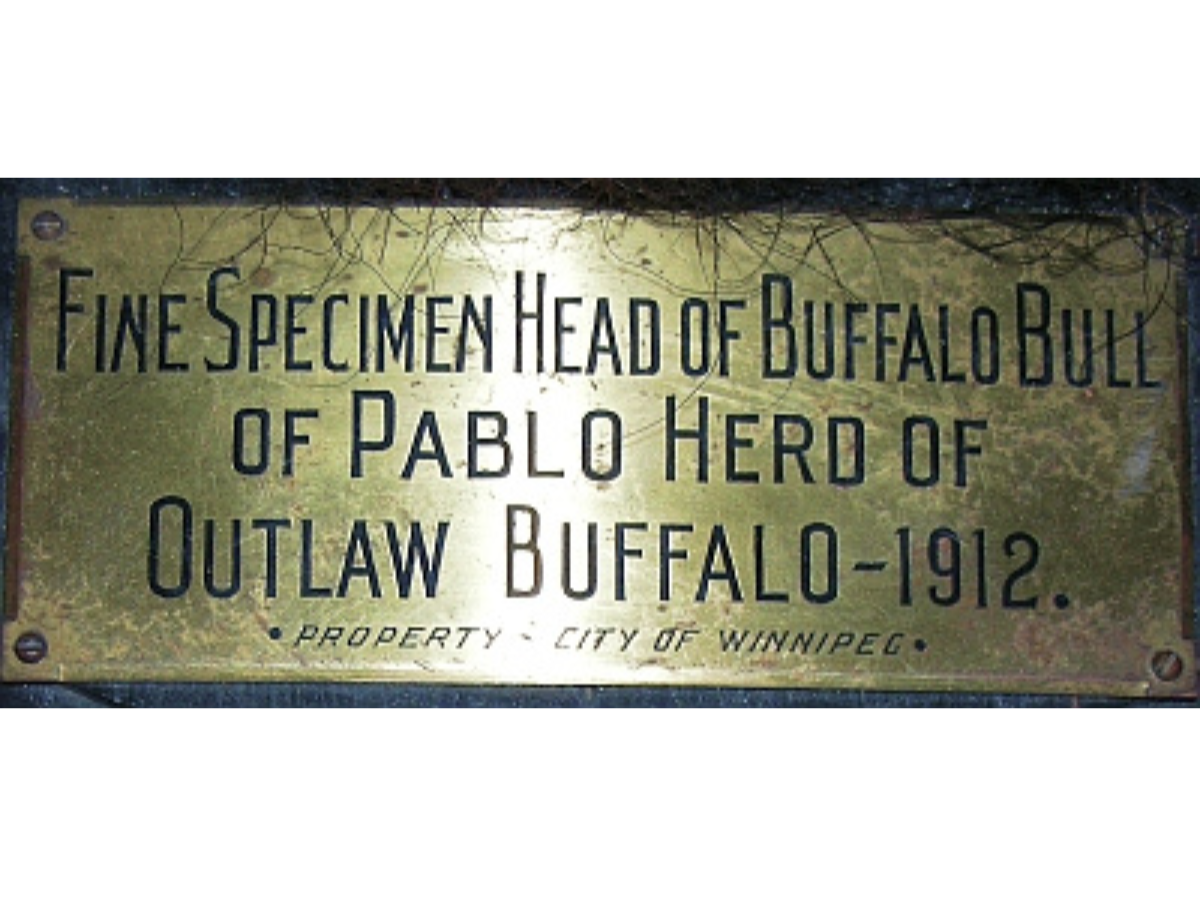

Although I have not yet determined how Outlaw #5 came to be in the possession of The Hingston Smith Arms Co. Ltd. (they are not listed as purchasers at the auction), documents generously shared by the City of Winnipeg Archives show that in January of 1912 that company offered to hang the head in the City Council Chambers. This was in order for it to “be seen to advantage” and determine if Council would be willing to purchase it. After all, it was “the finest specimen of Buffalo Bull Head” and “the best one of the lot of out-law bulls of the Pablo herd.” It seems most of the Council agreed, as only one month later they voted 10 to 7 to buy the head for $750 – equivalent to over $18,000 today! And they engraved the description much as boasted by the company onto the plate that adorns the backboard:

So as Outlaw #5 stares haughtily down on visitors today, he is both a symbol of our capacity to destroy and an incredibly important symbol of our potential, as Manitobans and Canadians, to be better stewards of our nation’s spectacular natural world.

Affectionately dubbed “Pablo” by Programs staff, the Museum’s outlaw bull of the Pablo-Allard herd is an impressive reminder of change since Confederation and ironic symbol of national conservation efforts. (MM 24175)

Confederation has fostered the diversity of perspectives that will help us through environmental challenges and that will work towards solutions over the next 150 years. Our exhibit might not provide the kind of birthday celebration we are likely to see on July 1st, but instead encourages a more sobering and reflective look at Confederation from a Manitoba viewpoint – how it happened, where we’ve been, and where we’d like to go. The incredible artifacts and specimens we have had the privilege to exhibit and interpret provide signposts to guide that thoughtful reflection.

Legacies of Confederation: A New Look at Manitoba History is open until January 7, 2018 and is free with admission to the Museum Galleries.