Explore the stars from your own backyard! This page has resources for budding astronomers and scientists of all ages. Build your own star clock, track the International Space Station, connect with local Manitoba astronomy groups, and more.

The Northern Lights

- SpaceWeatherLive.com offers forecasts for northern lights visibility on their website or via an app for IOS and Android.

- On Facebook, the Manitoba Aurora and Astronomy group tracks local sightings and shares information on how to observe and image the northern lights in Manitoba.

Safe Sun Viewer

Use a cardboard box to safely view the sun during a solar eclipse! Follow the bilingual instructions at the Canadian Space Agency!

Build a Star Clock

- Build a Star Clock to tell time using the Big Dipper. Download the file here.

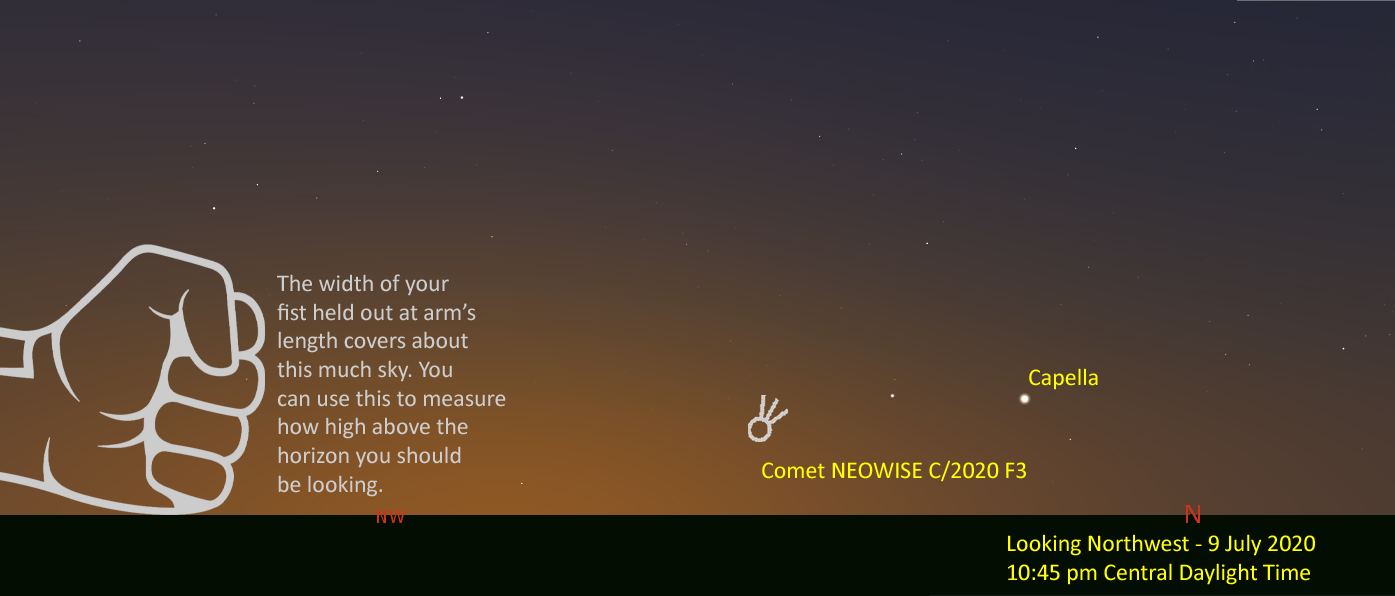

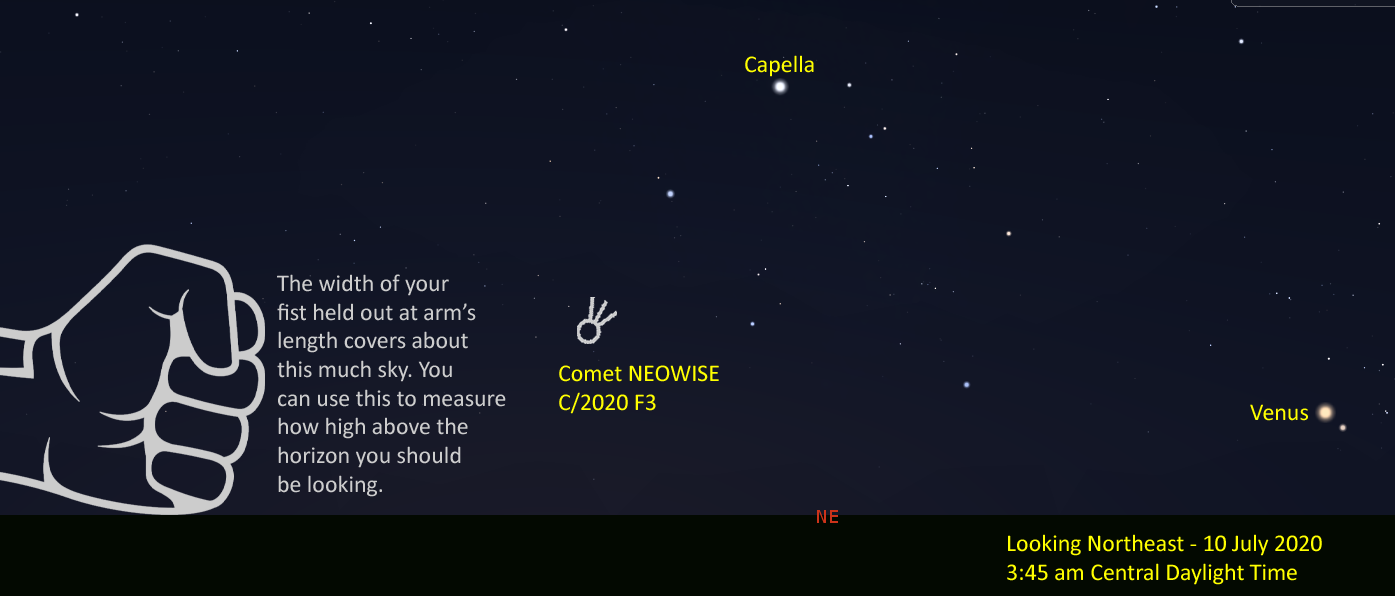

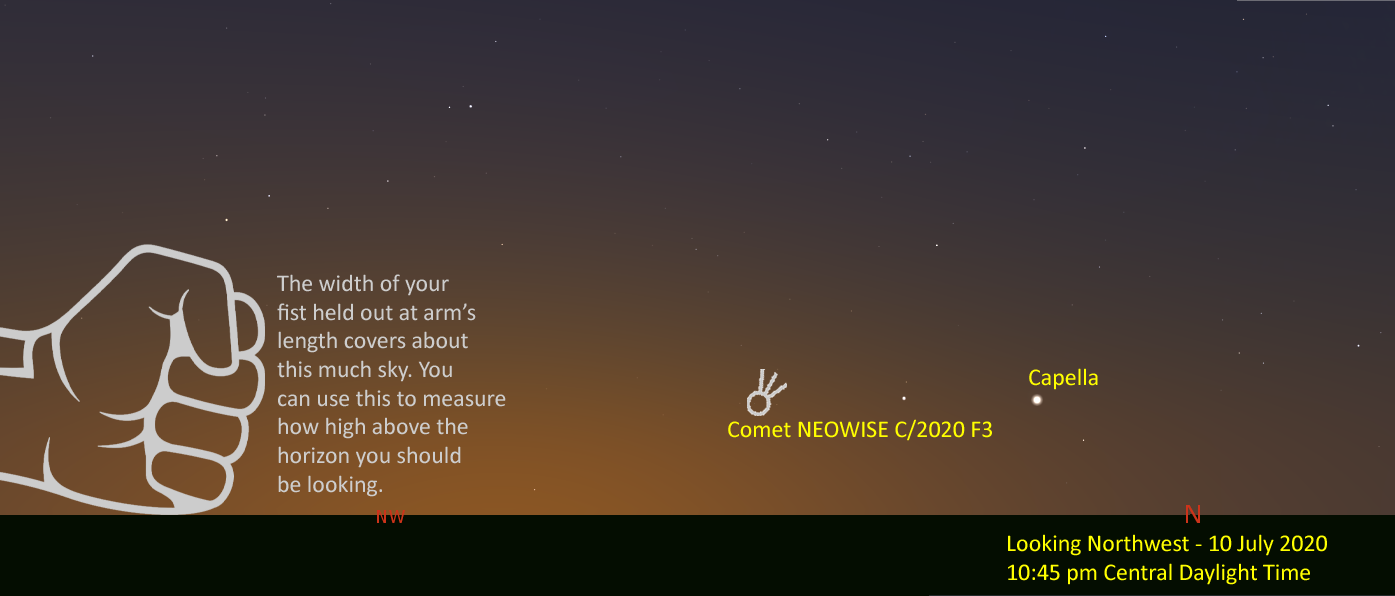

Exploring the Sky

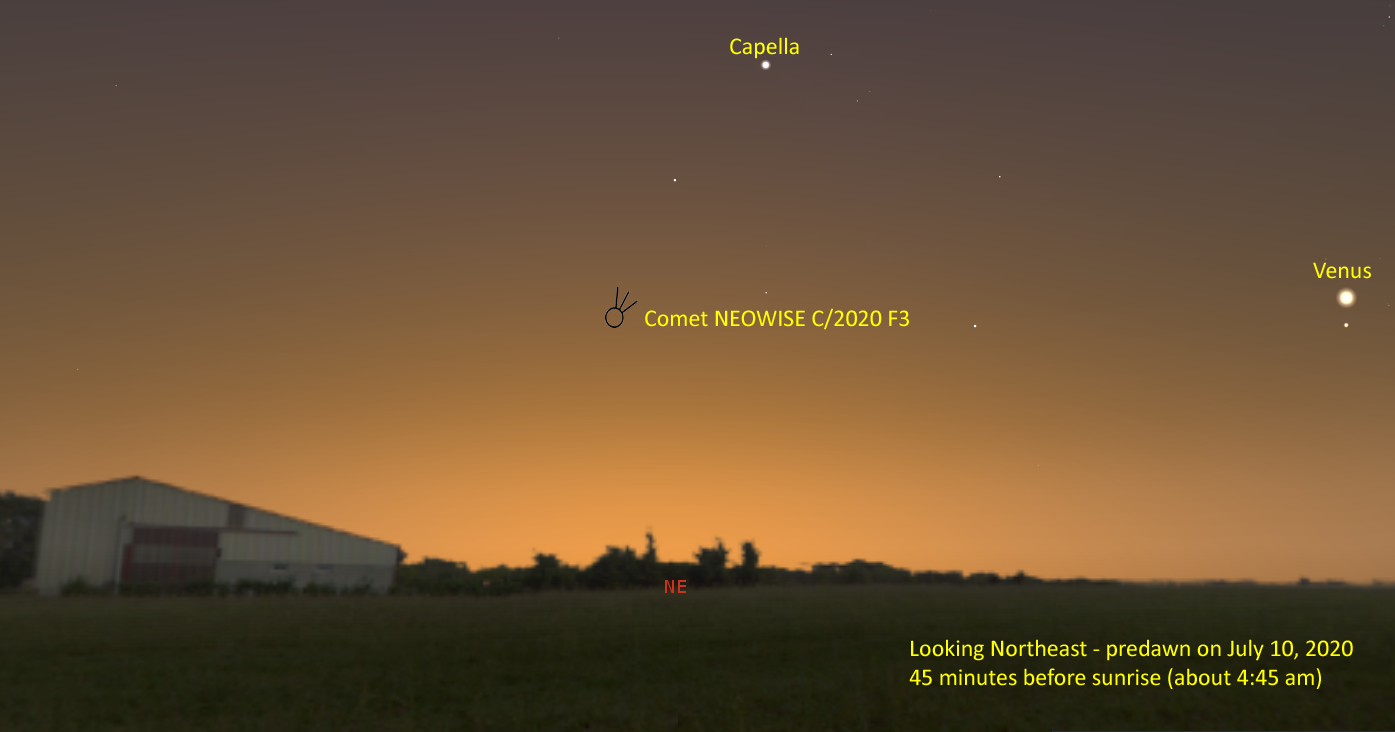

- See what’s up in the night sky with Manitoba Skies, our monthly sky blog!

- International Space Station sightings from Winnipeg

- Cloud Forecast for Astronomers – astronomy-specific cloud forecast for Winnipeg.

- Create your own star map at Heavens Above.

General Astronomy Information

- Buying a telescope: recommendations on how and where to buy a telescope in Manitoba.

- SpaceWeather.com: information on solar activity and northern lights visibility.

- Sunrise and Sunset times for cities in Canada

Astronomy Groups in Manitoba

- Royal Astronomical Society of Canada: Winnipeg Centre – the local astronomy club, with over 200 members from all walks of life.

- University of Manitoba Astronomy Group – information on the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Manitoba.

- Other Canadian Astronomy Clubs

Astronomy Publications

- SkyNews Magazine – the Canadian magazine of amateur astronomy. Lots of current information and useful links for amateur astronomers of any level.

- The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada publishes several books useful to amateur astronomers in Canada.

- Sky & Telescope Magazine – daily information updates, star maps, and a wealth of information for the amateur astronomer.

Astronomy Education Resources

- The Astronomical Society of the Pacific – excellent site for teachers with lots of resources, lesson plans, and products for astronomy education. The site is based on the American curriculum but is still useful for Canadian teachers.

Space Exploration

- The Canadian Space Agency (CSA) – bilingual site covering Canada’s contributions to the exploration of space.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) – general NASA sight with everything you need to know about the space shuttle, space station and more. Lots of links to other NASA sites.

- Hubble Space Telescope – images and history of the Hubble Space Telescope.

First step: educate yourself. Pick up

First step: educate yourself. Pick up