Posted on: Tuesday November 4, 2014

Part III in a three-part series.

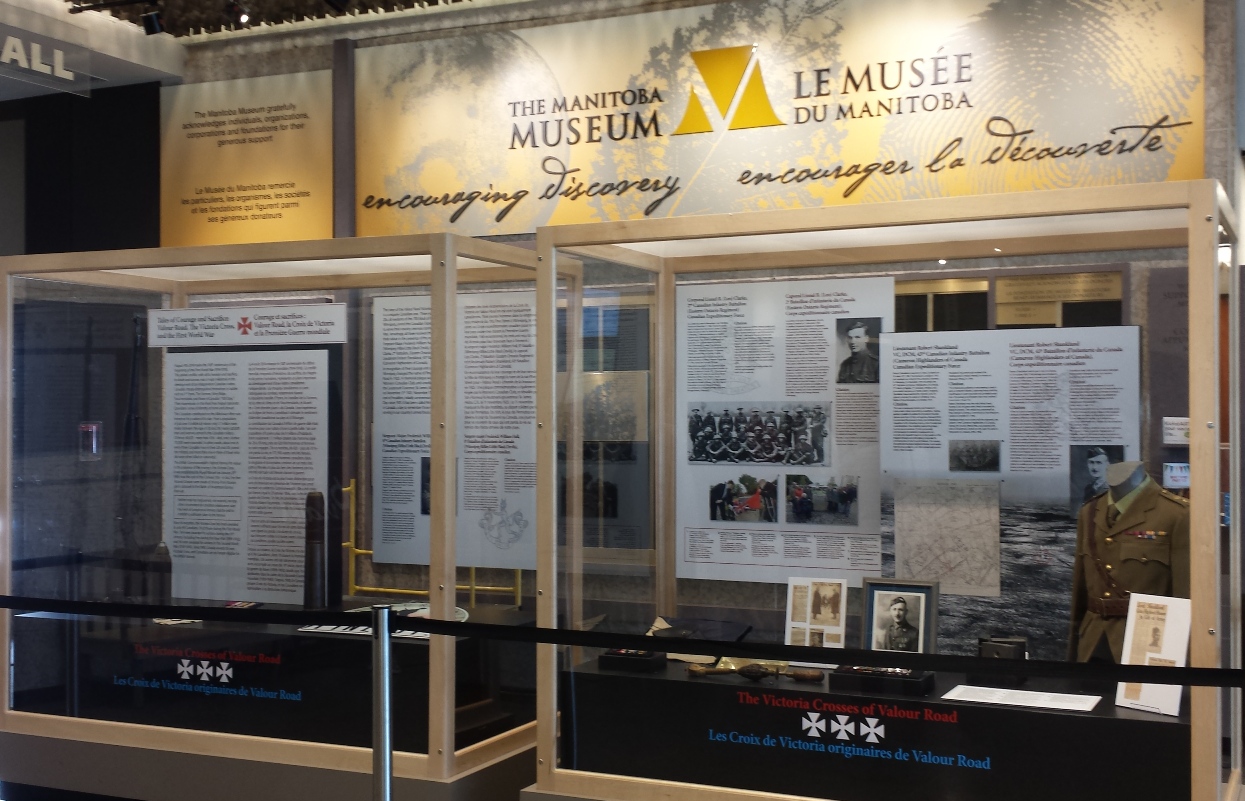

As we enter the last weeks of our exhibit “Victoria Crosses of Valour Road”, which ends on Sunday, November 16, I want to give some attention to how the First World War ended and some of its implications. My blog entry is illustrated with WWI postcards from the Museum’s collections.

In the summer of 1918 the Germans and their allies had made their final push against the west, and they had failed. Their troops, finances, and population were exhausted and there was serious unrest at home. The counter attack by the Allied forces, strengthened by a major influx of Americans, stormed over western Germany in the fall of 1918. On the eastern front, Bulgaria had decided to leave the German alliance, opening a route for attack as well. Austria-Hungary, which had started the war, was being torn apart by military desertion based on multiple ethnic-nationalist movements. By the end of September, the highest levels of German command were recommending an armistice of some sort, but not “surrender”. They felt a treaty could be negotiated, but in fact they had no position of strength from which to negotiate. By the end of October, revolutions were breaking out around Germany, led initially by the German navy. Wilhelm’s authority was broken, and he was “informed” that he had abdicated on November 9.

This postcard was sent to Mrs. Manchester, of 32 Lipton St., Winnipeg MB. The soldier is probably her son Stewart John B. Manchester, born in Souris, MB in 1888. He survived the war and went on to become a trainman for the CNR in Winnipeg. H9-21-755. Copyright The Manitoba Museum.

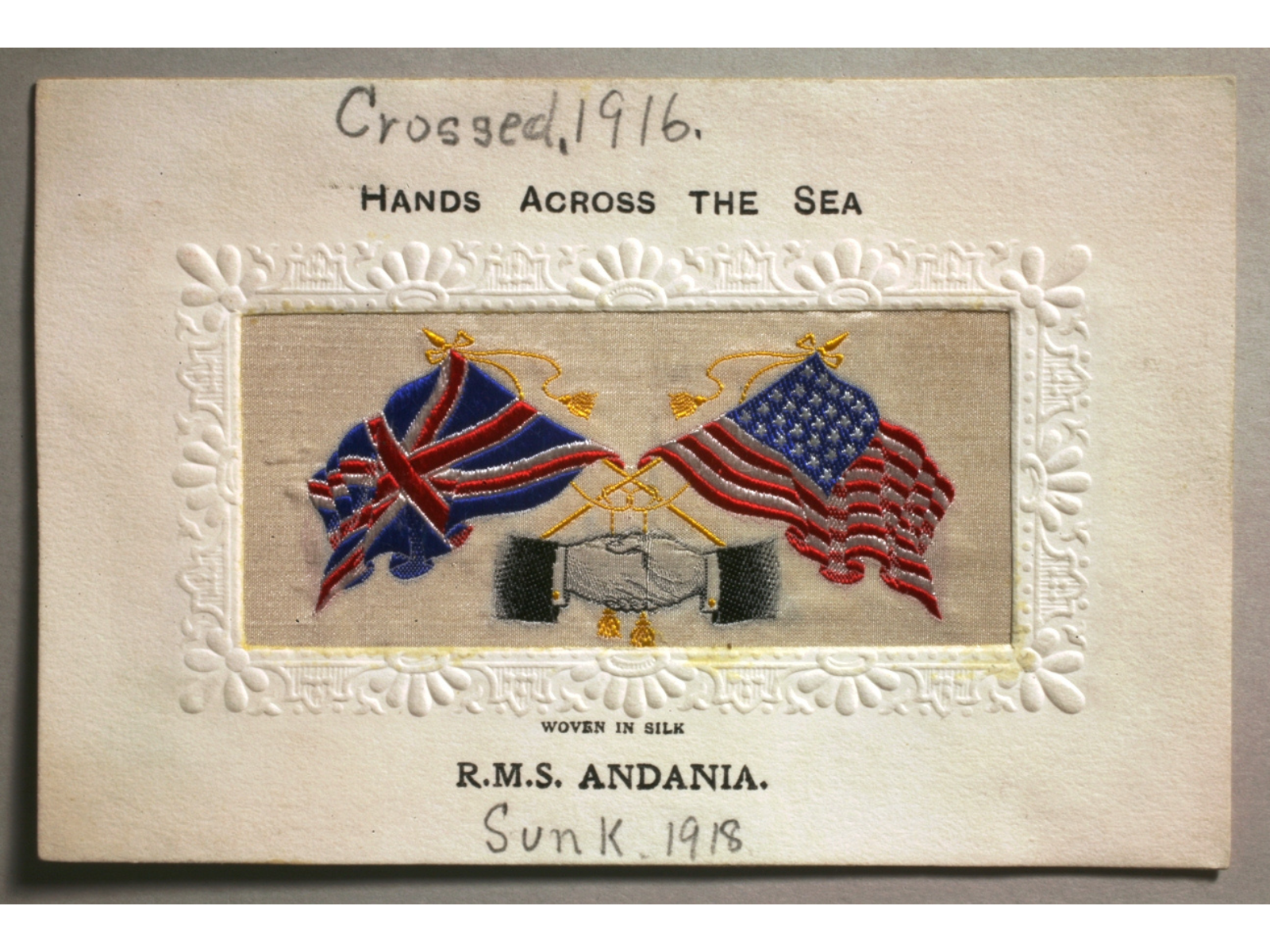

The RMS Andania was a passenger ship that was used to transport Canadian soldiers to Europe. In 1917 it returned to passenger service, but was torpedoed by a German submarine in 1918. The continued destruction of passenger ships by the Germans infuriated the Americans and the British and strengthened their resolve in the final days of the war. H9-15-697. Copyright The Manitoba Museum.

The black humour in this Belgian postcard is unmistakable. Translated as “God is with us”, it makes fun of the German belief that God was on their side during the slaughter of WWI. H9-16-66. Copyright The Manitoba Museum.

At 11 am on November 11, the guns on the Western front were at long last silent. Unfortunately the greatest killer, the Influenza Pandemic of 1918, which would claim at least 20 million lives worldwide, was just getting underway…

What was accomplished by the Great War? On the surface, nothing. Germany retreated to its former borders, with a few small areas controlled by the allies, and their army and navy were decimated. But the allies suffered even more human losses.

To make it all “worth it”, the allies concocted the Treaty of Versailles, a punitive arrangement in which Germany and its allies, though not believing they had “lost”, were forced to pay massive amounts in reparations to the French and Belgians in particular. Regular Germans were furious, since it was their government, not they themselves, who were responsible for the war. These reparations, which Germany could never afford, led in part to a collapse of the German monetary system and widespread poverty, and helped to fuel the rise of the Nazis less than 20 years later. Remember that Hitler enlisted in the First World War, and used Germany’s treatment at the hands of the Allies as justification for many of his later actions.

Not surprisingly, many British and Canadian troops also believed God was on their side. H9-15-470. Copyright The Manitoba Museum.

This postcard depicts Great Britain as the lion, and the colonies and dominions as his “cubs”. Canada is the cub on the right. They are attacking a German general to help defend Belgium. H9-16-140C. Copyright The Manitoba Museum.

Back in Canada, tales of heroism and sacrifice, along with the thousands of dead and missing family members lost in the war, seem to have provided Canadians with a new sense of national identity that, while not divorced from the British Empire, was perhaps more robustly independent. On a more practical side, tens of thousands of soldiers returned home looking for work, to find that women had entered the workplace. In a bid for “fairness”, many women were laid off to make room for men. The Communist Revolution in Russia had also inspired workers worldwide to feel that labour could make social change. In Winnipeg, many of the strikers in the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 were returned soldiers.

The political and social ramifications of the First World War seem endless, but certainly “old” Europe, with its aristocracy and its entrenched class systems, was severely tested and in some cases swept away.

War Memorial, Wawanesa, Manitoba. Photograph by Roland Sawatzky.

This postcard depicts both dead soldiers and a heartbroken family. The postcard as a form of public mourning was a powerful acknowledgement of the real-life effects of the war. H9-15-469F. Copyright The Manitoba Museum.

Now the common man was seen as the suffering hero. Seventy-one Victoria Cross medals were awarded to Canadians for their service in WWI. Memorials were built by the thousands to commemorate the soldiers who lost their lives with an emphasis on names, dates of death, and ranks. To the best of its ability, society attempted to remember the individual. Governments around the world encouraged this trend, seeing it as conservative and socially integrative – and a far cry from the radical social movements they feared, like Communism (or the Winnipeg General Strike). These memorials can be seen all over Manitoba, from Memorial Boulevard in Winnipeg to many rural town parks (like Wawanesa). These memorials became the focal points of public mourning, such as Armistice Day, which was largely observed by families and friends of the deceased at Thanksgiving. It was not until 1931 that Remembrance Day as we know it was created by the federal government on the annual date of November 11.