Posted on: Wednesday May 6, 2015

Last time I blogged, I listed five of the most popular food plants that were cultivated by America’s First Nations peoples. Today I bring to you the final five.

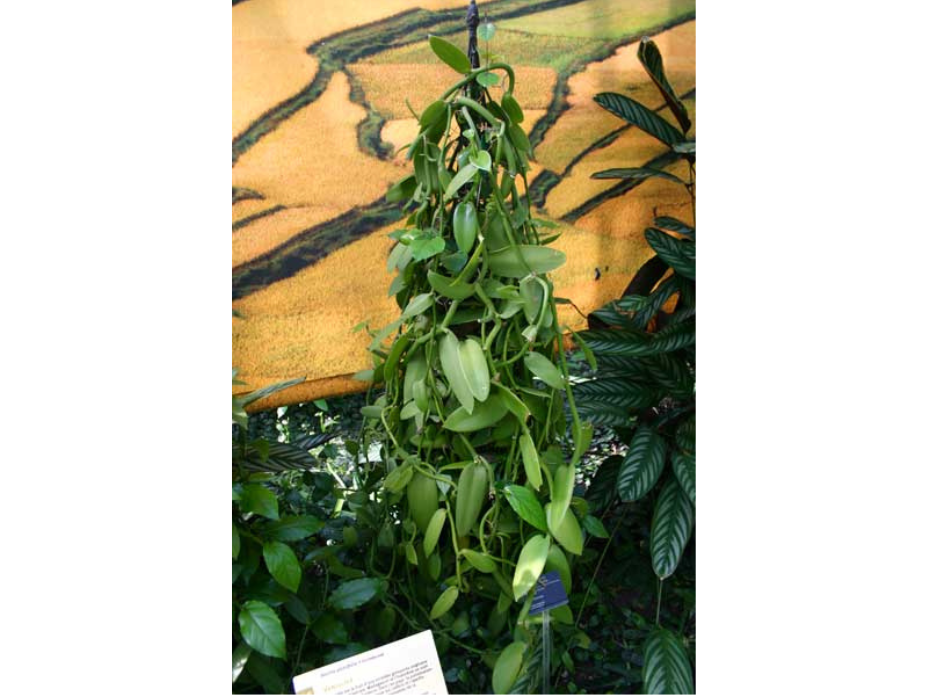

5. Vanilla (Vanilla planifolia)

Vanilla is considered to be the world’s most popular spice as well as the most popular ice cream flavour. It was the Totonac peoples of eastern Mexico who first began cultivating vanilla; eventually this spice was taken to Europe by Hernán Cortéz in the 1520’s. Initial attempts to cultivate vanilla orchids outside of central and South America were unsuccessful because the plant can only be pollinated by wild, stingless bees. Once hand pollination was discovered, vanilla plantations outside the Americas were created. Although we call the vanilla fruits “beans” they are not related to the legume family at all; vanilla fruits are actually capsules.

Image: A vanilla orchid plant growing in the greenhouse at the Montreal Botanical Garden.

4. Corn (Zea mays)

What visit to a movie theatre would be complete without a big bag of popcorn? Corn is the most widely grown plant in the world. It was originally cultivated in central America starting about 7,600 years ago. Archaeological evidence indicates that corn was being cultivated by Manitoba’s First Nations in the 1400’s (Learn more about Manitoba’s First Farmers here). Corn is eaten directly as a fresh vegetable, and dried as cornmeal or flour. Indirectly it is an ingredient in many processed foods. When not overly processed, corn is healthy, containing fibre and polyphenols.

Image: Corn plants were traditionally used by First Nations to make shoes and dolls. These shoes are in the First Nations Garden at the Montreal Botanical Garden.

3. Tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum)

Imagine a world with no pizza, no ketchup, no salsa, no ratatouille, no chilli! It would be awful! It is precisely because tomatoes have been absorbed into the cuisines of so many cultures that we tend to forget that they came from central and South America. Ironically, the healthfulness of the much lauded Mediterranean diet is at least partly due to the embrasure of this American plant as a key ingredient in many dishes.

2. Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum)

The most widespread and important vegetable in the world is the humble potato. Cultivated for over 7,000 years by the Incas of South America, potatoes were brought to Europe by the Spanish. Many Europeans were initially suspicious of the potato because it is in a plant family with many poisonous species. But once they accepted it there was no turning back. Potatoes have found their way into just about every cuisine and are prepared in a multitude of ways. Let’s see, there’s boiled potatoes, fried potatoes, mashed potatoes, sautéed potatoes, potato pancakes, potato curry…

1. Chocolate (Theobroma cacao)

Quite probably the most loved food plant of all for its ability to induce feelings of bliss, chocolate was discovered and cultivated in Amazonia and Mexico over 2,000 years ago. Traditionally cocoa was mixed with corn, chillies, vanilla, and water to make a spicy beverage. The Spaniards brought chocolate to Europe in the 1500’s but the chocolate bar as we know it wasn’t invented until the late 1800’s. Nowadays dark chocolate is considered healthy due to its high polyphenol content (woo hoo!), and hot chocolate has become the traditional beverage for winter sporting events.

Image: These are the flowers of the cocoa tree. Soon they will become cacoa beans. Mmmm cacoa, most beloved of beans!

I haven’t exhausted the list of First Nations crop plants that are still being cultivated today which includes allspice, amaranth, avocado, papaya, pecans, sunflowers, and sweet potatoes to name a few. Clearly, world cuisine would be much poorer without the crop breeding efforts of the First Nations.