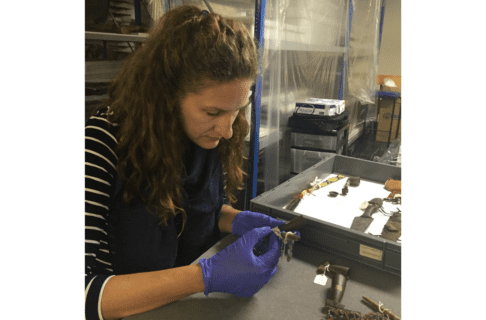

By Cortney Pachet, Collections Registration Associate, Human History and former Assistant Curator for the HBC Museum Collection when Amelia was on parental leave.

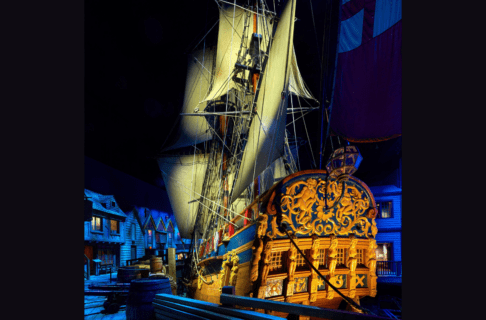

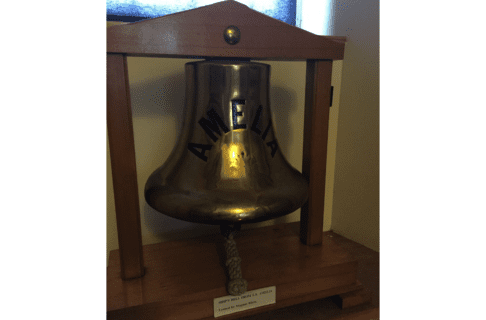

The Hudson’s Bay Company has a long nautical history, from the Nonsuch to countless canoes and York Boats to steamers, paddlewheels and schooners. While the majority of HBC’s travel and transport took place on water, we also see a pattern of the Company’s vessels meeting untimely ends in tragic wrecks.

Princess Louise (aka Olympia) – sank

Anson Northup (aka Pioneer) – sank

S.S. Beaver – Wrecked

Cadborough – Wrecked

Labouchere – Sank

Baymaud – Sank

Mount Royal – Wrecked

Aklavik – Caught fire, sank

Nascopie – Wrecked

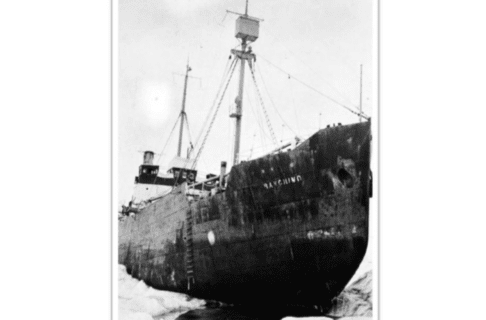

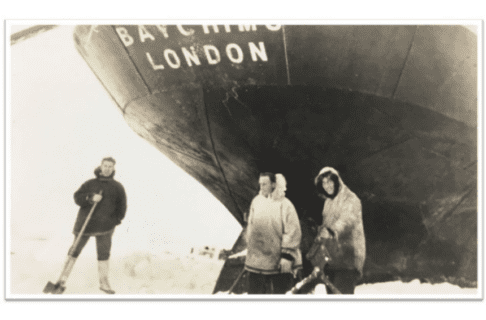

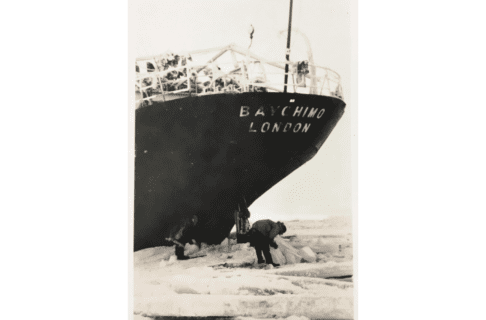

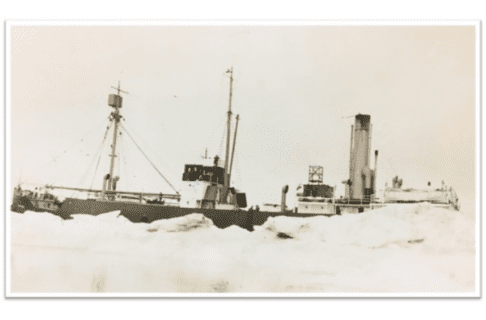

The Baychimo, a steamer based in the Western Arctic, finds herself amongst these ill-fated vessels, but exactly how she met her end remains one of the biggest mysteries in HBC history.

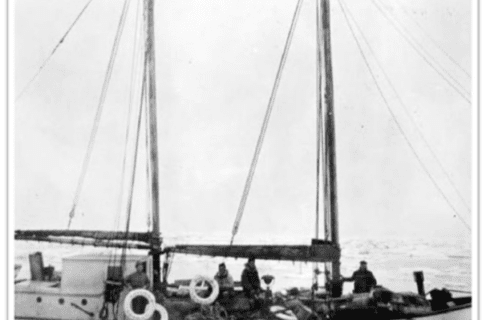

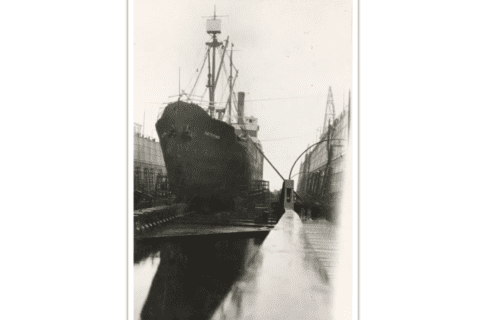

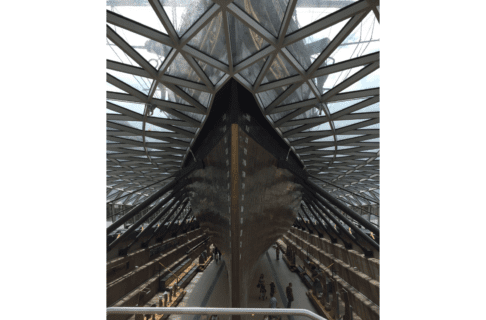

Designed and built at Lindholmens Verkstad AB (Aktiebolag) in Gothenburg, Sweden, she was originally christened Ångermanelfven after one of Sweden’s longest rivers, Ångerman. The vessel had a steel hull, was 230 ft (70.1 m) long, and powered by a triple expansion steam engine. She was also outfitted with schooner rigging.

Ångermanelfven launched in 1914 and was used as a trading vessel for her German owners around the Baltic Sea. The ship continued to serve Germany’s Baltic posts through WWI, protected by the Imperial German Navy.

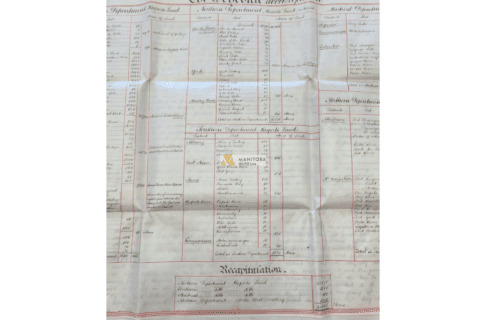

Following the Great War, Ångermanelfven was ceded to the British government by Germany in 1920 as part of war reparations negotiated at the Treaty of Versailles, article 244, Annex III: “Germany recognizes the right of the Allied and Associated Powers to the replacement, ton for ton and class for class, of all merchant ships and fishing boats lost and damaged owing to the war.”

Consequently, all German ships over 800 tons were confiscated and divided between France, Great Britain and the US. Ångermanelfven was sailed out of the Baltic Sea for the last time by a British crew, destined for London where she was put up for sale to commercial interests. The Hudson’s Bay Company purchased the Ångermanelfven for 15,000 pounds and she was renamed Baychimo, joining the company’s fleet of cargo ships.

Her first voyage for HBC took place in 1921, were she served in the Eastern Arctic, coinciding with the establishment of Pond Inlet. The following year, the Baychimo was sent to Siberia with Captain Sidney Cornwell at the helm. Cornwell enlisted with HBC to serve as Master of the Baychimo at the onset of the Kamchatka Venture in 1922. The Kamchatka Venture aimed to trade furs in Siberia, but a changing political climate caused the HBC to withdraw after only two years.

Like other HBC vessels, the Baychimo’s homeport was Androssan, Scotland and each year, she would travel to Scotland for the winter, returning to Canada by way of the Panama Canal. In 1924, the Baychimo sailed to the Western Arctic by way of the Suez Canal, meaning that in the course of her career, she accomplished global circumnavigation (Achievement Unlocked!).

Following the dissolution of Kamchatka Venture at the end of 1923, Baychimo was reassigned to the Western Arctic, traveling between Vancouver and HBC posts along the Yukon and Northwest Territories northern coast from 1924 to 1931. Later in her career, she would winter at Vancouver, including 1930 to repair damage to her rudder, propeller and steering.

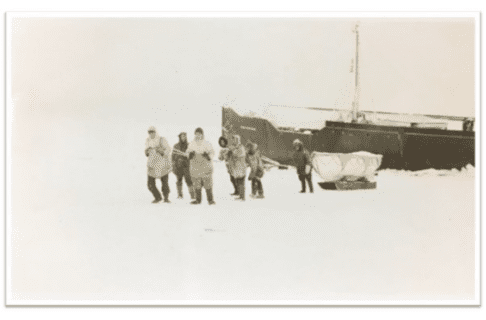

The Baychimo carried cargo to these Western Arctic HBC, RCMP, and missionary posts but also occasionally took a small number of passengers, who were listed as part of the crew since the vessel wasn’t classified as a passenger ship. The passengers would do jobs to pay for their room and board. On average, the Baychimo had a crew of 32.

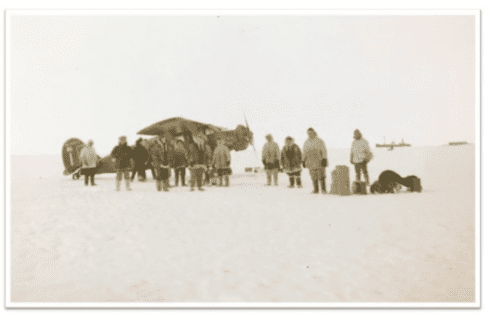

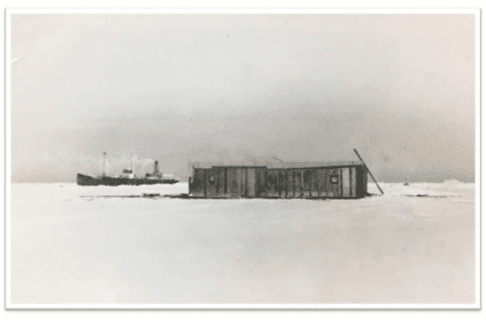

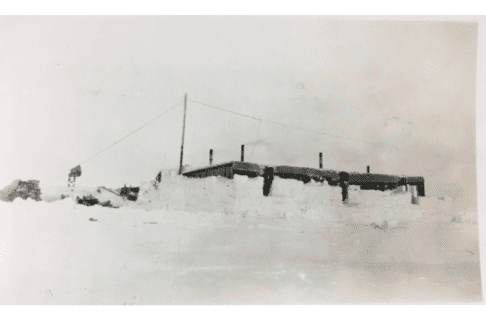

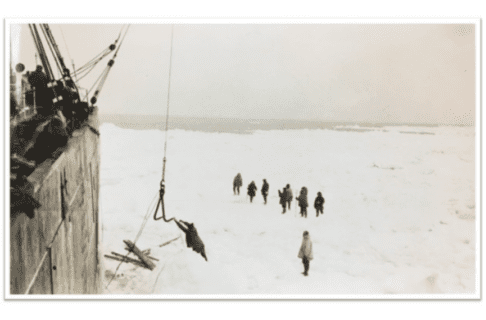

In late September, 1931 on her way back to Vancouver, the Baychimo was surprised by a blizzard at the Sea Horse Islands, near Point Barrow on Alaska’s northern coast and the crew was forced to anchor the Baychimo to weather the storm. It soon became apparent that the steamer was caught in ice and would have to overwinter in the Arctic. Using parts of the ship, the crew began construction on winter accommodations for the crew that would remain behind with the ship until the spring. The large Baychimo couldn’t be heated all winter long, so the wooden and snow structure was a warmer and safer alternative. The crew removed food and other supplies from the vessel as they set up camp. Her passengers and some of her crew were flown to Kotzebue, Alaska and on to Vancouver. Maintenance of the ship’s rudder was a daily chore for the remaining crew, keeping ice from building up around this critical piece of equipment.

At the end of November, another storm swept through and when it cleared, the Baychimo was gone. The captain and crew assumed the vessel had sunk, but they soon received word that an Inuk hunter had spotted the Baychimo, once again packed in ice, roughly 72 km south of their encampment. Captain Cornwell and the crew made their way to the Baychimo and boarded the vessel, removing a large quantity of furs and abandoning the ship for the last time, determining that she was no longer seaworthy after ricocheting solo through the icy waters of the Beaufort Sea. Furthermore, the Baychimo was caught in ice once again, so she wouldn’t be going anywhere anytime soon, right?

WRONG!

Captain Cornwell and the remaining crew were flown back to Vancouver in March of 1932, where paperwork was filed for the loss of the vessel and the negligible cargo left behind. Shortly thereafter, the Baychimo was spotted again but about 480 km to the east of where the crew had last seen her. The following March, she was seen floating peacefully near the shore of Alaska by Leslie Melvin, a man travelling to Nome with his dog sled team.

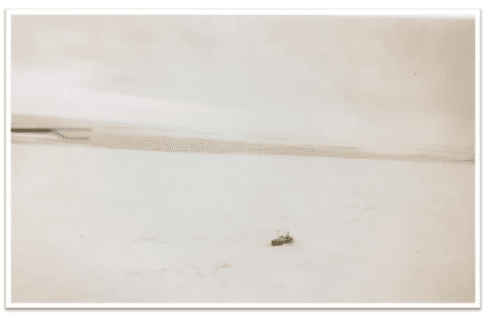

In the decades that followed, many people would spot the Baychimo, now dubbed the “Ghost Ship of the Arctic” as she traveled long unencumbered by crew and cargo.

- March 1933, she was found by a group of Indigenous Alaskans who travelled to her, boarded her and were trapped aboard for 10 days by an unexpected storm.

- In the summer of 1933, she was boarded by the crew and passenger of Trader, a small schooner from Nome, Alaska. The single passenger was a Scottish botanist named Isobel Wylie Hutchison on an expedition to collect Alaskan and Arctic wildflowers. The crew of Trader reported that at the same time, a group of Inupiat boarded the ship, having travelled out to her by umiak and removed mattresses, chairs and other items like Sunlight dish soap, tarpaulins, a bucket of sweet pickles and a silver toast rack from the vessel. The following day, the Baychimo had once again disappeared, although Trader crewmembers repeatedly spotted her “hurrying north in her private ice pan” later in their journey toward Herschel Island in Yukon.

- September 1935, she was seen off Alaska’s northwest coast.[1]

- November 1939, she was boarded by Captain Hugh Polson, wishing to salvage her, but the creeping ice floes intervened and the captain had to abandon her. This is the last recorded boarding of Baychimo.

- After 1939, she was seen floating alone and without crew numerous times, but had always eluded capture. Recorded sightings slowed during WWII and in the subsequent years.

- March 1962, she was seen drifting along the Beaufort Sea coast by a group of Inuit.

- She was found frozen in an ice pack in 1969, 38 years after she was abandoned. This is the last recorded sighting of Baychimo.

In 2006, the Alaskan government began work on a project to solve the mystery of “the Ghost Ship of the Arctic” and find an estimated 4,000 ships lost along the coast of Alaska. She has not yet been found, but given that 50 years have elapsed since her last sighting, it’s likely that the Baychimo is resting at the bottom of the Beaufort Sea.

Although the Baychimo’s impact on HBC operations was fairly uneventful, her legacy as the Ghost Ship of the Arctic is one that persists in the narrative of the company’s history.

Images: Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba, HBHL photo collection subject files, 1987-1363-B-1111-751922-1931, H4-198-4-6