By Dr. Graham Young

Past Curator of Paleontology & Geology

Walking into the Manitoba Museum’s Earth History Gallery, you see an enticing undersea scene in the middle distance. Passing through an opening, you find yourself in a small room that feels like an underwater observatory.

Here in the Ancient Seas exhibit, a giant curved screen wraps around two walls, and on that screen you see projected a coral-lined boulder shore, with strange and wonderful sea creatures: large cephalopods similar to a “squid in a shell” swim in the water, flower-like crinoids wave in the dappled sunlight, and giant trilobites related to crabs and spiders plough through seafloor sediment. This submarine world represents our best understanding of what the Churchill area looked like about 450 million years ago during the Ordovician Period, long before polar bears or mosquitoes appeared on this planet.

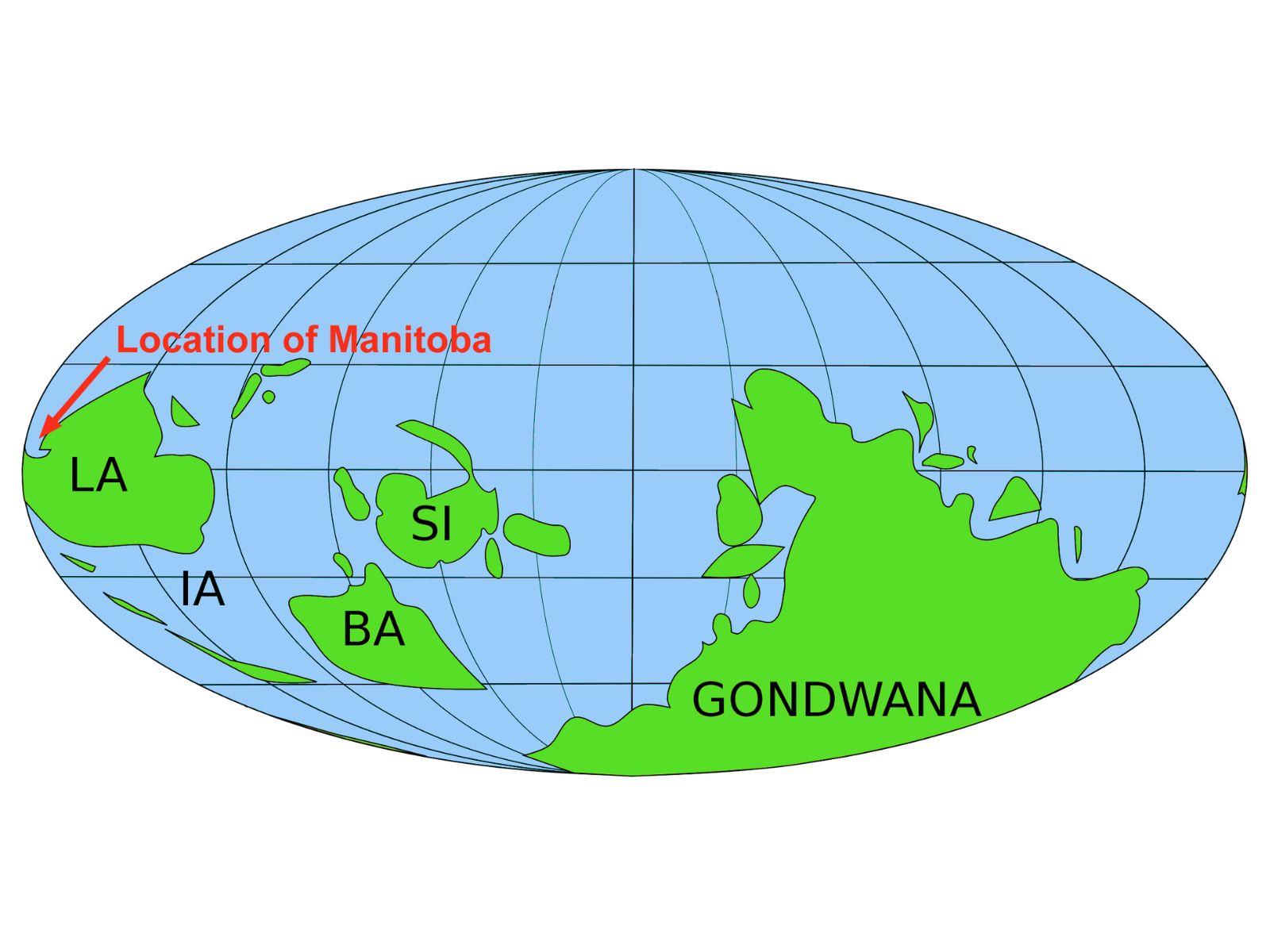

In this beautiful exhibit, one of the things visitors find most remarkable is the statement that Churchill was tropical, that “Manitoba straddled the equator and had a warm climate.” How can Manitoba have moved so much? The simple answer is that Manitoba has moved as part of a much bigger land mass. In the Ordovician Period, the heart of North America was already a distinct continent, called Laurentia by geologists.

Just like continents do today, the ancient continents were moving by the process of plate tectonics. Land masses move toward or away from one another at about the same rate your toenails grow, an average of about 1.5 cm per year. If you move a continent at that speed over 450 million years, it can travel a very long way! Ordovician Laurentia was moving toward ancient parts of Europe and Africa, and more than 100 million years later this resulted in the formation of Pangaea (the “world supercontinent”) about 335 million years ago. After Pangaea pulled apart 200 million years ago, North America moved northwestward, eventually arriving where we are now!

During the Ordovician Period, 450 million years ago, what is now the “heart of North America” formed the ancient continent of Laurentia (LA), and Manitoba was near the equator. As time passed, Laurentia would move toward the other ancient continents such as Baltica (BA) and Siberia (SI), closing the Iapetus Ocean (IA). These land masses would eventually join with Gondwana to form the “world supercontinent” called Pangaea.

Exhibits like Ancient Seas tell us about this place in very different past times. Many of the people in Manitoba came here from distant places, and now we also know that the land itself has travelled, and changed almost beyond recognition. At the Museum you can see some of that distant past, and appreciate our former worlds.