Posted on: Monday September 12, 2011

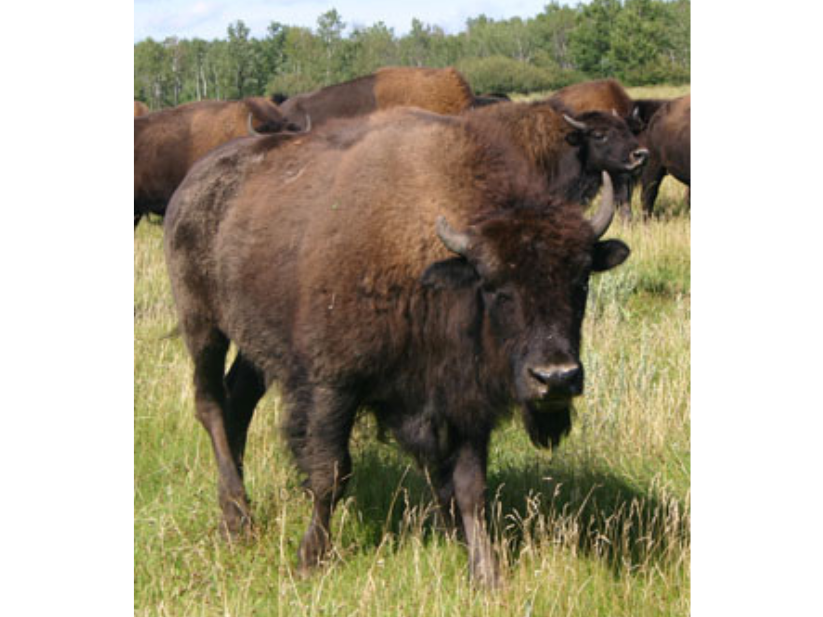

A lot of conservation initiatives around the world involve fencing off areas to “protect” the wild species contained within. Although that strategy can work well in ecosystems that are rarely disturbed, like tropical rainforests, it doesn’t work as well in ecosystems that evolved with natural disturbances. North American prairies used to contain migratory herbivores (e.g. bison, antelope) that consumed large quantities of the vegetation. Bison are unique in that they also engaged in extensive wallowing activities, creating permanent bowl-shaped depressions on the landscape. Old journal entries from some of the first European explorers describe bison herds as taking days to pass and leaving huge swaths of trampled and disturbed soil in their wake. Wild fires following drought and lightning strikes were also common. Native annual plants like ragweed, goosefoot, and bugseeds were likely adapted to colonize these disturbed areas.

Some human activities mimic those of bison.

Buffalograss benefits from heavy grazing.

Nowadays certain human-related disturbances mimic those of the bison. Cattle grazing is somewhat similar to bison grazing and is likely responsible for the continued persistent of the rare Buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides) in the Souris River valley. Without grazing, Buffalograss would likely be outcompeted by taller grasses and exotic weeds.

In sand dune habitats, where I was doing field work last week, I found rare plants like Bugseeds (Corispermum sp.), Hairy Prairie Clover (Dalea villosa), Winged Pigweed (Cycloloma atriplicifolium) and Bearded Nut-sedge (Cyperus squarrosus) growing on the sandy edges of gravel roads, on fire guards, in sand pits, and on beach dunes where the feet of many a bikini-clad pedestrian had trodden. Clearly certain human activities can help provide habitat for these rare annuals, acting if you will as substitutes for wild bison.

Image: Trampling by humans may help create habitat for rare bugseed plants at Grand Beach.

Although a moderate amount of disturbance is necessary to create the habitat these rare plants need, too much disturbance is a bad thing. I was unable to relocate some of the historical populations of bugseeds because the areas where they had grown in the past were now heavily impacted by humans and our machinery, being dominated by weeds introduced to Canada from Europe and Asia. Clearly, finding the right balance of disturbance, not too much and not too little, is important for the conservation of certain rare plants.

Dune cutaways along roadsides in sandy areas provide habitat for rare bugseed plants.

Bearded nutsedge grows on bare sand.

The observation that disturbances are sometimes beneficial has led many scientists to conclude that both controlled burns and the re-introduction of bison (or the tolerance of cattle grazing) is essential for the conservation of prairie habitats. Sand dunes are in particular need of disturbance as nearly a quarter of the rare species on Canada’s endangered species list are restricted to open or lightly vegetated sand dunes. Less than 1% of the sand dune ecosystems in the prairies consist of open dunes. So ironically, protecting a species may mean tolerating and even facilitating a little bit of what appears to be destruction.

Image: Winged pigweed grows on natural sand dunes and on fireguards at CFB Shilo.