Posted on: Thursday February 6, 2025

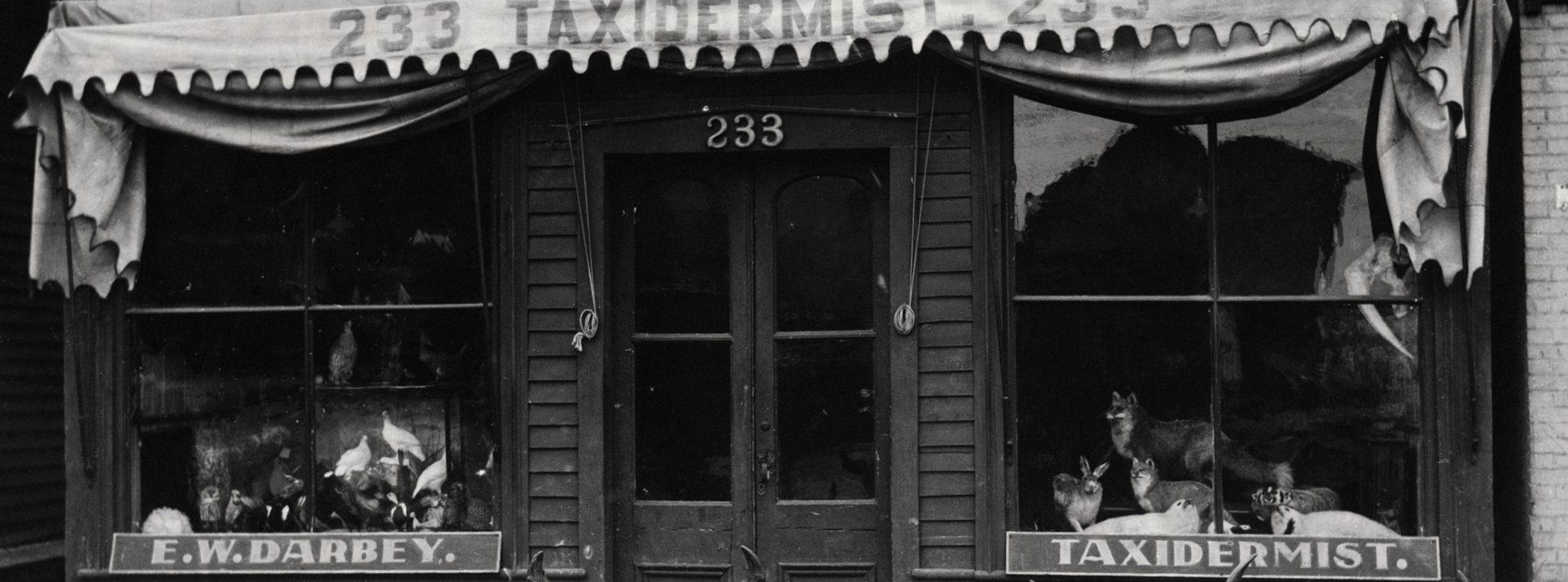

Taxidermy storefronts, like that of E.W. Darbey on Main Street in 1911, were stuffed with unusual animals and birds (note the seals and walrus, far right), beckoning casual visitors as well as buying customers. Detail, L.B. Foote Collection N1660, Archives of Manitoba.

The Manitoba Museum recently opened a “new” store in the Winnipeg 1920 Gallery, the Darbey taxidermy shop. Today, a taxidermy shop would be considered a minor player in our digital world of cell phones, apps, and AI. But from 1880 into the 1920s, taxidermy was an important element of Manitoba society. Many homes, particularly wealthy ones, displayed hunting trophies and stuffed birds. These functioned as conversation pieces and expressions of social status. Public spaces were adorned with game heads as symbols of the province’s natural riches. Government-sponsored travelling exhibitions used taxidermy to promote Manitoba as overflowing with resources awaiting exploitation and profit. The aim was to attract businesses and immigrants from other parts of Canada and from around the world.

The Golden Age of Winnipeg Taxidermy

Through this promotion, Manitoba became a destination for big game and bird hunters, even royalty. Trophy hunters from further west, on their return to the east, would stop at Winnipeg to have their prizes prepared. This meant taxidermy was in high demand in the city. By as early as 1891 there were at least four separate taxidermy businesses operating within just a few blocks of each other, right along Main Street – and the population of Winnipeg was only about 26,000 at the time!

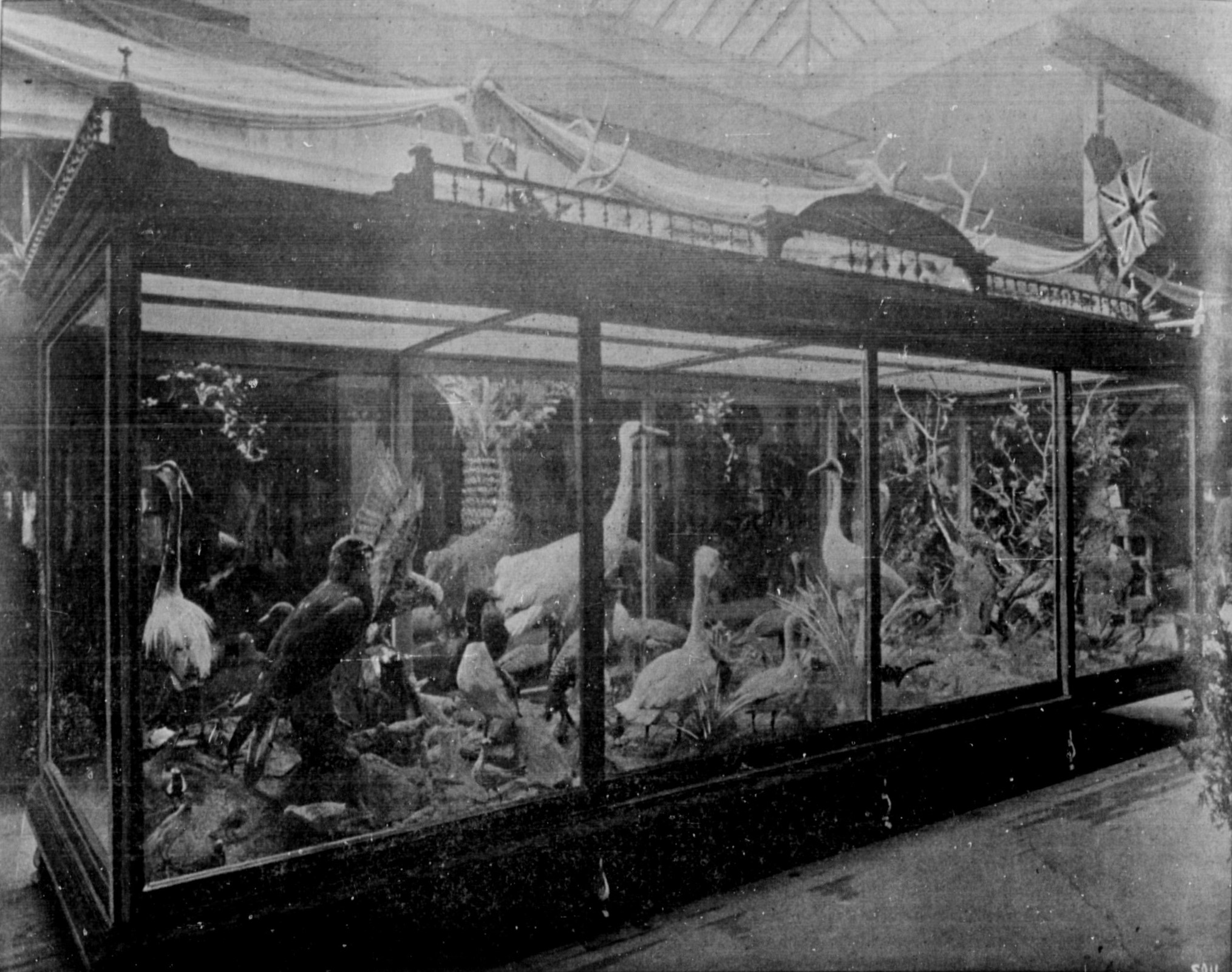

Image: Taxidermy exhibited in the Manitoba Pavilion at Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, much of it likely the work of the Hine family of Winnipeg. Such displays emphasized the natural bounty of the province to attract visitors, sportsmen, and immigrants. From Winnipeg Daily Tribune Supplement, August 26, 1893.

It was page-one news in the (then) Manitoba Free Press, albeit accompanied by sarcastic humour, when Winnipeg’s first taxidermist, George Nagy, arrived on the scene in August of 1879:

Nagy did not advertise as a taxidermist, but as a furrier who also “stuffed” moose and deer heads, and birds. Nagy was soon replaced by those specializing in taxidermy, with the first listing of “Taxidermists” in the classifieds of the 1882 Henderson Directory naming the Hine family – father Abel and son William – under that category. They were later joined by Abel’s younger sons Calvin and Ashley. This family received acclaim in England and across North America for their work, with Ashley becoming a noted bird taxidermist for Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History in the 1920s and 30s.

Competition from additional taxidermists began in earnest between 1890 and 1900 with the arrival of George Grieve, Alexander Calder, Edmund Wilson and his sons, William White, and smaller operators. There was substantial cross-pollination of talent; the hired help, or the main players themselves, often moved between establishments. For example, Calvin Hine worked variously with his father and brother, with Grieve, with White, and also independently. One of White’s employees, Edward Darbey, was able to learn taxidermy and marketing from some of the best, and he used that experience to full advantage.

An example of Darbey’s work, an albino crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) now in the Manitoba Museum collection. MM 3-6-452 © Ian McCausland, Manitoba Museum.

Darbey himself in his field attire. Winnipeg Free Press, August 26, 1922.

The Rise of Edward Darbey, “Official Taxidermist to the Manitoba Government”

Edward Wade Darbey was born in 1872 in southern Ontario and arrived in Winnipeg with his parents in 1887. By 1892, he had become an apprentice and clerk to William Fenwick White, a well-known taxidermist and “curio” dealer on Main Street. The early 1900s saw significant upheaval on the Winnipeg taxidermy scene. The untimely deaths of long-time taxidermists George Grieve (in 1901, age 49) and William White (in 1905, age 45), along with members of the Hine family leaving Winnipeg for England, Alberta, or British Columbia, created a void – and opportunity. Edward Darbey took the taxidermied bison by the horns, as it were, and purchased Grieve’s established business. Darbey’s skill, business acumen, and ambition had him named as Manitoba’s official taxidermist, a unique position he held until his death in 1922. Darbey’s wife was equally ambitious and managed the business, using Darbey’s name and title as advertising, for several years after his passing.

Darbey’s letterhead proclaiming his title as taxidermist to Manitoba’s government. Taxidermy held a different place in society at the turn of the 20th century. From the C. Hart Merriam papers, p. 426, The Bancroft Library.

Taxidermy shops as “Museums”

Until 1932, there was no provincial museum in Manitoba. Before then, taxidermy and “curio” shops assumed that role. These were filled with an intriguing assortment of mounted birds and mammals. Some also carried an array of beautiful Indigenous beadwork, leatherwork, and archaeological items. They attracted not only buying customers, but interested visitors as well. And, as noted, there were several competing taxidermy shops to browse. One proprietor, William Fenwick White (where Darbey got his start), even advertised his shop as “White’s Free Museum.” Taxidermists were also sought for their knowledge on animal behaviour, distribution, and, paradoxically, conservation.

Winnipeg newspaper advertisements posted at the turn of the 20th century by William Fenwick White for his “Free Museum” of taxidermy, including two-headed calves along with more traditional mounts. First Nations beadwork and clothing was also featured. From left to right: Winnipeg Tribune, Sept 1, 1893; Winnipeg Free Press, Dec 12, 1894 and Dec 21, 1901.

Darbey’s Taxidermy Shop and the first Manitoba Museum

It was in this social atmosphere that Darbey’s taxidermy shop became a centre for local naturalists. His rise to prominence and resultant receipt of interesting specimens added to the attraction. Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946), the famous Canadian/American writer and Chief Naturalist for Manitoba, visited Darbey’s shop and relied on Darbey for bird and mammal records for his books and reports. Working under Darbey were excellent preparators and collectors, like Cyril Guy Harrold, who had local, national, and international connections. By 1920, informal get-togethers had led to the formation of the Natural History Society of Manitoba. It was members of this organization that championed, and won, a dedicated space for a provincially recognized museum in 1932. Although it had humble beginnings, just a small room in the Civic Auditorium (now the Archives of Manitoba), it was the predecessor to the present Manitoba Museum. Many of the collections in our vaults and on exhibit were inherited from this earlier incarnation.

Image: A peek through the window of Darbey’s shop as reproduced in the Winnipeg 1920 Gallery and into an important era of Manitoba history. © Manitoba Museum.

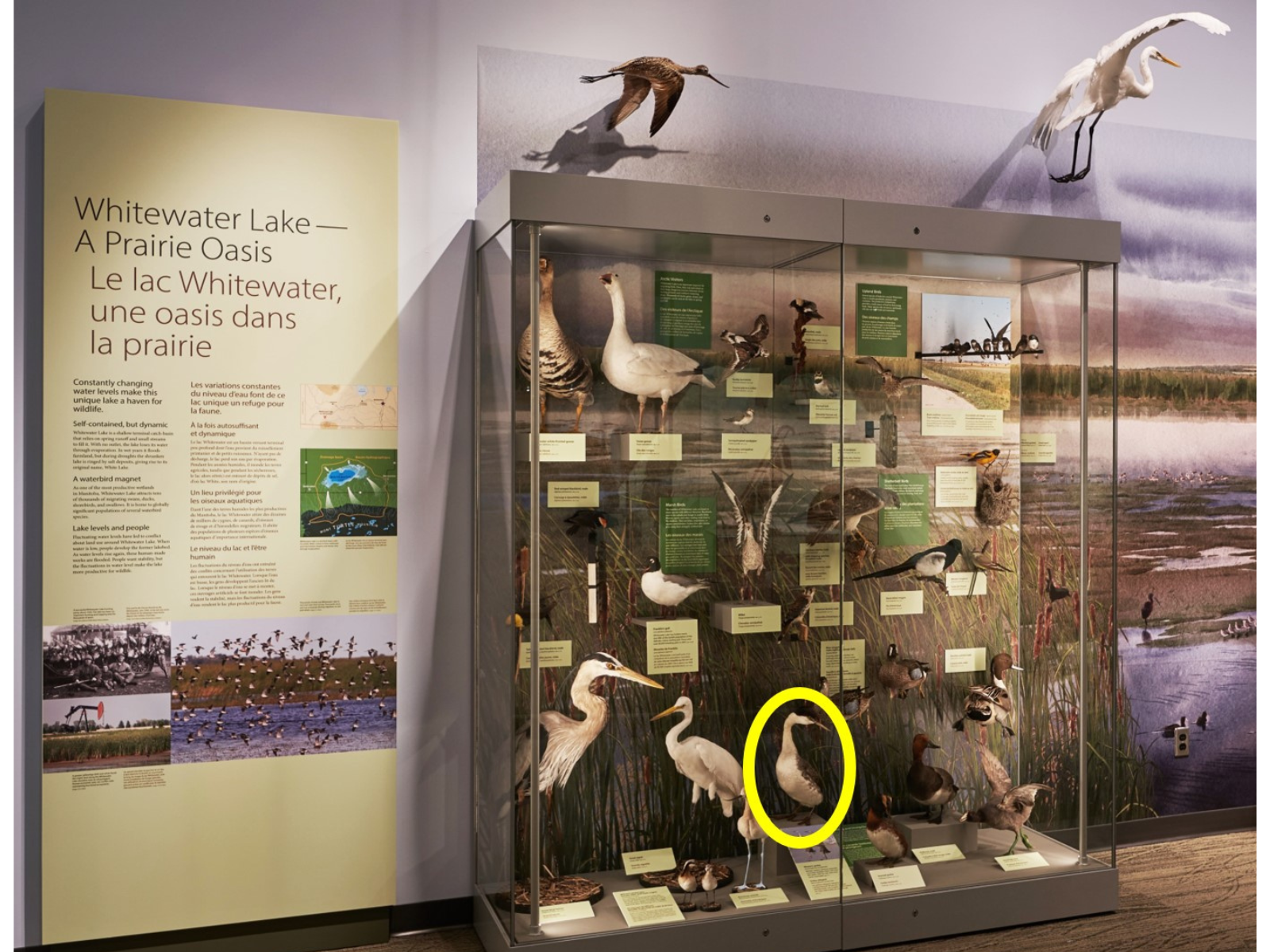

A beautiful Darbey mount of a western grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis) – circled in yellow on the left and as a closeup on the right – currently seen in the Whitewater Lake exhibit in the Prairies Gallery. Even after more than 100 years, Darbey’s work continues to have purpose and educate. © Ian McCausland, Manitoba Museum

We invite you to visit Darbey’s taxidermy shop reproduced in the Winnipeg 1920 Gallery and explore its amazing contents through the window it provides into the Winnipeg of over 100 years ago. And you can see some of Darbey’s original work in the Prairies Gallery, still drawing the eyes of intrigued visitors.