Posted on: Wednesday March 5, 2014

Recently, Melissa Pearn, our Cataloguer of Natural History collections went on maternity leave. She wrote this blog entry before she left.

As a Natural History cataloguer, I have the opportunity to work with some very interesting specimens. I love that my job involves all three areas of natural history – botany, zoology (mostly entomology), and palaeontology/geology. Having studied pollination and reproduction of Lady’s Slipper orchids for my Master’s thesis, I especially enjoy working with the botanical and entomological specimens. It’s fascinating to get to see some of the plants and insects that I have heard or read about, but have never had the opportunity to see in nature.

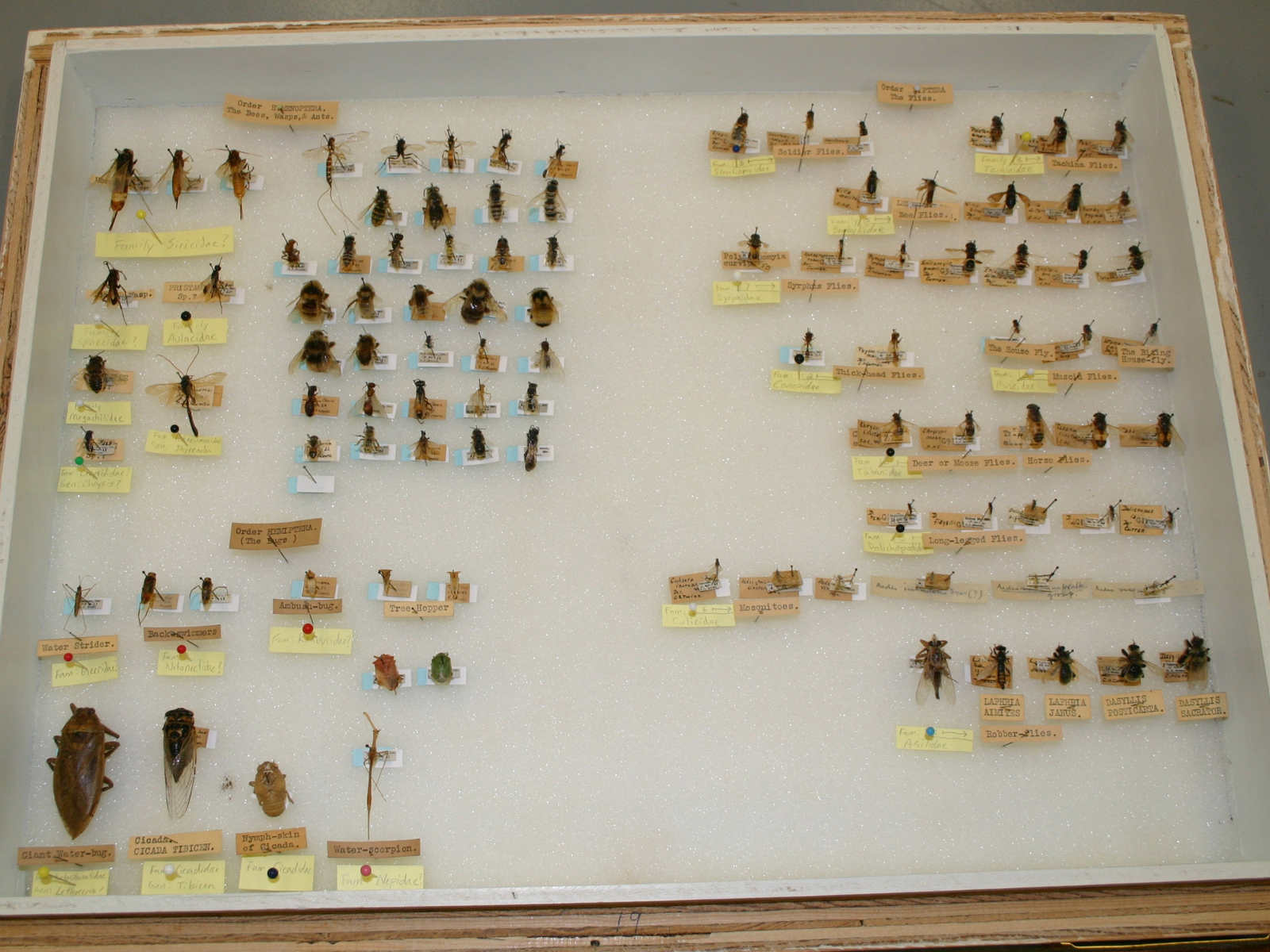

I’ve recently been cataloguing an interesting collection of Manitoba insects. The specimens were collected in the 1920’s and 1930’s, in places such as Victoria Beach and Winnipeg (especially Transcona). Not only is the collection fascinating because of its age and local origins, but also because of its diversity. Many of the specimens belong to the Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), but the collection also includes insects from 11 other groups such as Hymenoptera (ants, bees, and wasps), Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), Hemiptera (the true bugs), and Odonata (dragonflies), among others.

The collection was assembled by Manitoban naturalist and entomologist George Shirley Brooks. He was born in Wrentham, Surrey, England in 1872 and came to Manitoba around 1913. He was not only a founding member and president (1932-1934) of the Natural History Society of Manitoba, but also co-founder of The Manitoba Museum and author of “Checklist of the Butterflies of Manitoba”. He died in Winnipeg on October 20, 1947 and is buried at Brookside Cemetery.

Older collections such as this one are very valuable for the information that they contain. Because many specimens have a collection date and location, they can help researchers to evaluate and determine population trends over time, or to determine the status of rare species for example. In order to maintain the integrity of these types of collections, proper storage and handling are very important. In Natural History, specimens are stored in a collections room that is controlled to create just the right temperature, light, and humidity conditions. Under less than ideal conditions, or when on display for long periods of time, specimens can become altered, as can be seen with the faded coloring of some of the moths and butterflies in the Brooks collection.

Insect case with Hymenopterans (bees, wasps), Dipterans (flies) and Hemipterans (true bugs).

Storage case with insect groups Lepidoptera (moths) and Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies).

Two Luna Moth specimens. Though approximately the same age, the one on the left has become severely faded.

NOTE: Melissa had a healthy baby girl on Feb. 3. She is named Ivy. The Museum staff wish her family all the best.