Posted on: Monday August 29, 2016

Blog by Debbie Thompson, past Diorama and Collections Technician (Natural History)

Note: This blog contains descriptions and images that may not be suitable for sensitive individuals.

Most people pass by a dead bird, rarely giving it a second thought and leaving it where it lies. But there are many members of the public who notify the Manitoba Museum of the dead birds they do find, often from fatal encounters with windows. The Manitoba Museum appreciates the opportunity to salvage these, as it does not hunt birds to add to its Ornithology collection.

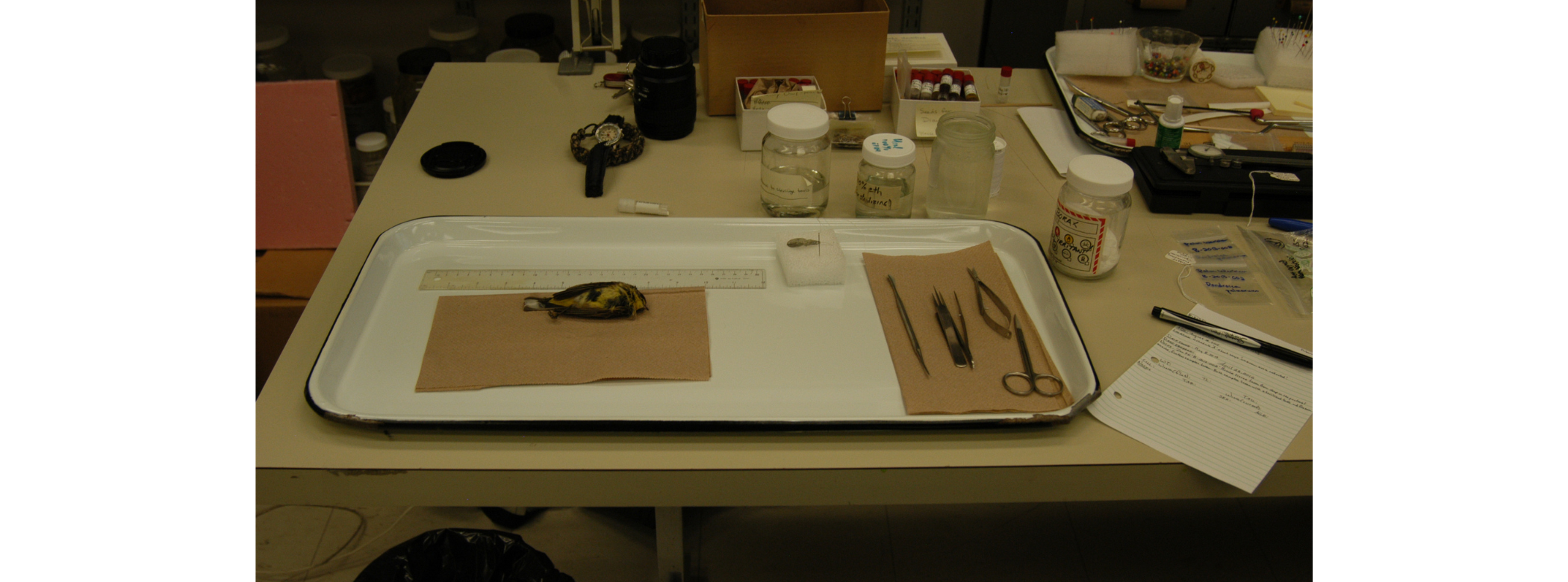

Before I start to process a bird, notes are taken: donor, collector, location, date of acquisition, when it was found and prepared; observations (broken bones, external parasites, molting, etc.); then scientific data, including weight, total length, tail length, wing size, beak and leg length. If possible, sex and age are determined by plumage and feather conditions, which are later confirmed through dissection. I use tools ranging from a simple ruler to surgical blades and scissors.

Tools laid out before beginning work on Palm Warbler. © Manitoba Museum

The first incision is along the breast bone, and then I free the skin from the abdominal cavity without puncturing the abdomen. I carefully free one leg at a time, removing muscle from the femur (= thigh bone) and then wrapping it in cotton and pushing it back into place with a bit of borax. The cotton recreates the muscle I have just removed to retain the bird’s natural shape. The borax aids in drying and preservation.

Once both legs are done, I work to free the skin from the rump/back, and then cut through below the pelvic area. The wings are done much the same as the legs. During this whole time, I am constantly taking notes on the amount, colour and location of fat deposits, locations of molting, any old injuries and internal parasites and anything else that may be out of the ordinary.

Image: Femur wrapped in cotton. © Manitoba Museum

The pattern on the top of the skull can reveal the age of the bird. If a large area is soft and transparent, the bird is a juvenile; if it’s hard and opaque, it indicates an adult. The brain and the eyes are removed and the skull filled with cotton.

The body is reshaped with cotton wrapped around a wooden dowel and the skin is pulled up around it. The incision along the breast bone and abdomen is sewn up. Often, the feathers need a gentle cleaning, with special attention to primp the plumage. The bird study skin is wrapped in a cloth ribbon to hold the wings in place and is pinned to a foam sheet to dry in a special drier.

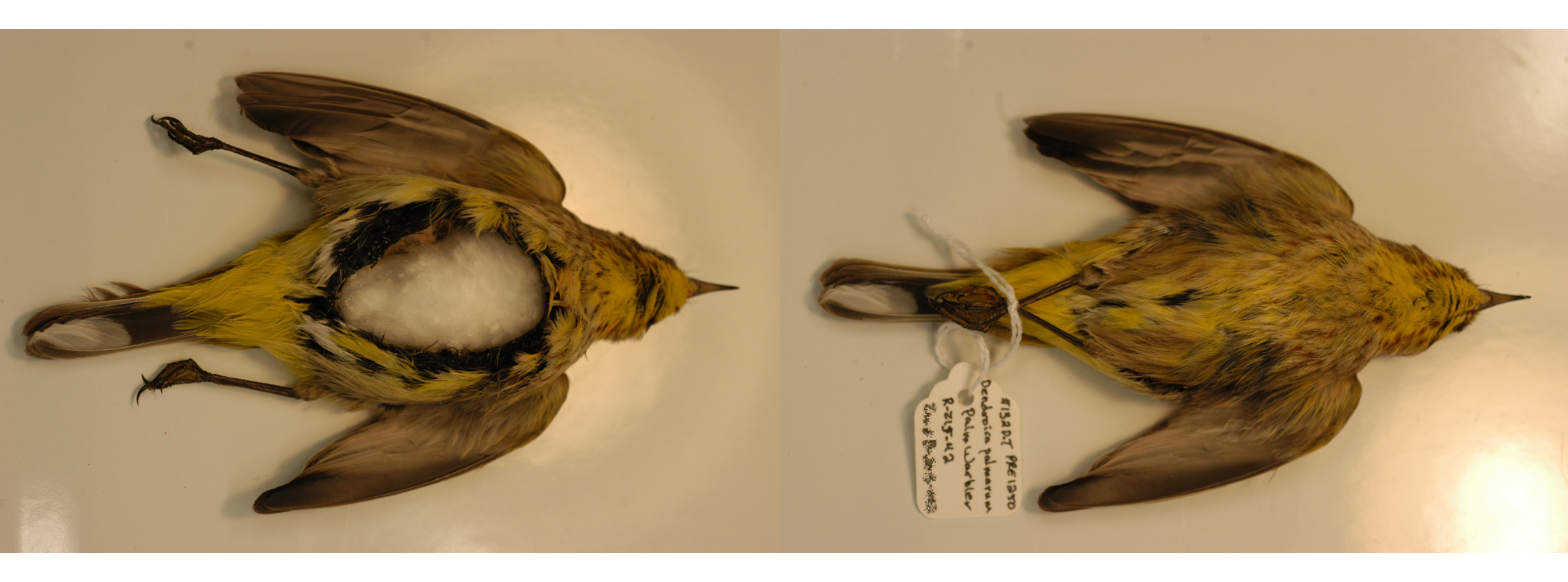

Left to right: Palm Warbler (#132 DT) – body cavity filled with cotton; body cavity sewn closed and feathers primpted. © Manitoba Museum

Left to right: Palm Warbler (#132 DT) – study skin wrapped and pinned to foam; finished bird study skin. © Manitoba Museum

Using a microscope, I confirm the sex of the bird and measure the testes or ovary. Determining whether the female bird has laid eggs, I search for the nearly invisible oviduct. If it’s straight, then the female hasn’t laid a clutch, but if it appears convoluted, she has laid eggs. I also look for internal parasites (such as roundworms), and then examine the stomach contents, noting everything found within. By far, the scariest of the stomach contents have to be spiders. Eye to eye and larger than life under a microscope, I jump every time I find one!

With patience and respect, it takes about 3 ½ hours to prepare a bird the size of a warbler. The study skin and data collected will aid researchers in the future, and any and all information I am able to collect is invaluable, a lasting legacy of a bird’s untimely death. The contributions to research are greatly enhanced when the public becomes involved, sharing with us their own discoveries and interest in the environment around them.