Posted on: Friday November 16, 2018

by Janis Klapecki, Collections Management Specialist (Natural History)

The Manitoba Museum receives calls daily inquiring if we are interested in receiving artifacts or specimens for our collections. They may have collected some clam shells while on a family outing to the beach, or have found some “treasure” in Great Aunt Muriel’s attic. We never know what to expect until we actually see the item.

In the spring of 1993, we received a call from a woman near Arborg (Manitoba) asking if we would be interested in receiving a butterfly collection. That may sound unusual to some, but for museum staff that work with insects, it’s a common conversation and potentially a good acquisition. What WAS unusual was where the butterflies were currently being stored…… the caller described that they were in a derelict van on the property they had recently purchased! After hearing this, we imagined the worst and didn’t expect to bring much back to the museum. Dried insect collections are highly susceptible to mould and live insect activity. A collection that is exposed to either of these factors can be completely destroyed within days.

Not actual derelict vehicle, but you get the idea. © Andy F / Austin van decaying in a derelict shed, Broadwell / CC BY-SA 2.0 / Geograph.org

Butterflies from this collection still in their original glassine envelopes. © Manitoba Museum

Once back at the Museum, the entire collection was placed in our large freezer for pest treatment. This is done to ensure that we aren’t inadvertently bringing in any live insect pests that could damage the Museum’s galleries and collections. When the 2 week freezer treatment period was complete, we started the massive task of inventorying the collection. The collection consisted exclusively of butterfly and moth specimens. There were upwards of 400 expertly pinned specimens with data labels, and approximately another 200 specimens still in their original glassine collection envelopes. As our work progressed further into documenting and cataloguing each individual specimen, we realized that it included some very special and rare specimens.

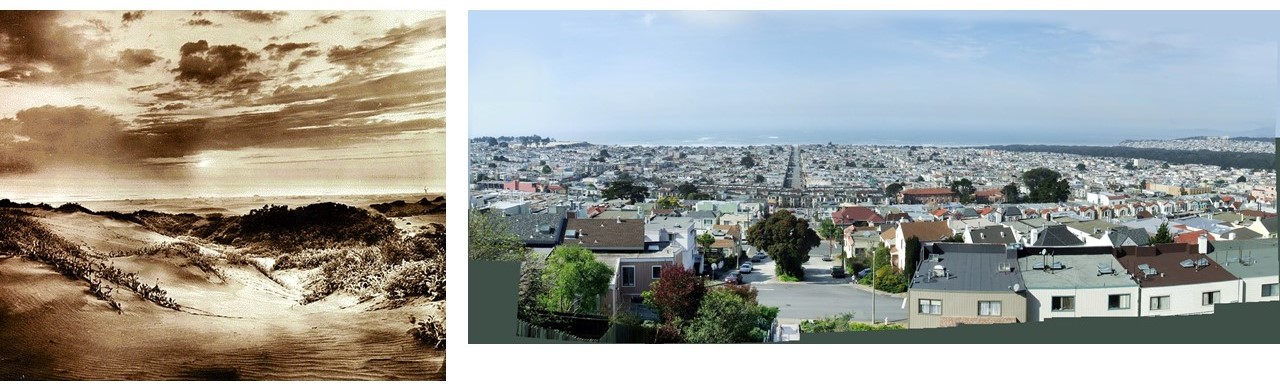

Among the many specimens of this collection, one species stood out. There were 26 specimens of an extinct butterfly, the Silvery Blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus xerces; Family Lycaenidae). They were collected in the 1920s by R.F. Sternitzky from the dunes of what is now the Sunset District of San Francisco, CA. This butterfly was endemic to the almost uninhabited coastal sand dunes of this area at that time. The species was first documented in that area in 1852, and is believed to have become extinct by the mid 1940s, when the dunes were scraped clear and houses completely replaced the dunes. Its extinction was directly attributed to urban development and habitat loss that included dune plants that the species relied upon for food and egg laying.

Image: Glaucopsyche lygdamus xerces butterflies collected by R.F. Sternitzky in San Francisco, c. 1920s © Manitoba Museum

Among the many specimens of this collection, one species stood out. There were 26 specimens of an extinct butterfly, the Silvery Blue (Glaucopsyche lygdamus xerces; Family Lycaenidae). They were collected in the 1920s by R.F. Sternitzky from the dunes of what is now the Sunset District of San Francisco, CA. This butterfly was endemic to the almost uninhabited coastal sand dunes of this area at that time. The species was first documented in that area in 1852, and is believed to have become extinct by the mid 1940s, when the dunes were scraped clear and houses completely replaced the dunes. Its extinction was directly attributed to urban development and habitat loss that included dune plants that the species relied upon for food and egg laying.

L-R: Sunset area dunes, San Francisco, circa 1900. San Francisco sand dunes, c.1900, /Foundsf.org / CC BY-NC SA 3.0. Sunset District, San Francisco, today. © Mike Woods / Urban Sunset / Flickr/MikeWoods / CC BY-SA 2.0.

The majority of the butterflies and moths were collected by R.F. Sternitzky in the coastal regions of California in the years ranging from the 1920s to the 1940s. There isn’t a lot of personal information on the web about R.F. Sternitzky, other than he was born in California (1891-1980) and spent a life time collecting mostly butterflies and moths (also some bees, flies, and ants) in parts of California, including the San Francisco Bay area, and in his later years, Arizona. He contributed significantly to Lepidopteran (moth and butterflies) collections and subsequent research as is evidenced by the numerous ecological and taxonomic publications online that refer to his specimens. His specimens are deposited in several large American museum collections including the the Essig Museum of Entomology (University Of California, Berkeley, CA), Bohart Museum of Entomology (University of California, Davis, CA), Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (New Haven, CT), the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (Washington, DC), the Harvard Museum of Natural History (Cambridge, MA), the American Museum of Natural History (New York, NY), as well as in Canadian museums such as the Canadian National Collection (Ottawa), and now the Manitoba Museum (Winnipeg).

These specimens, and in fact all specimens of permanent scientific collections all over the world, represent invaluable time capsules of the flora and fauna of that time, and of that space. We cannot go back and reproduce those dune habitats prior to human encroachment and development.

Thankfully the donor of this butterfly collection recognized that these specimens should be inspected by the Museum experts – otherwise they may have ended up in the local dump.

The mystery still remains….

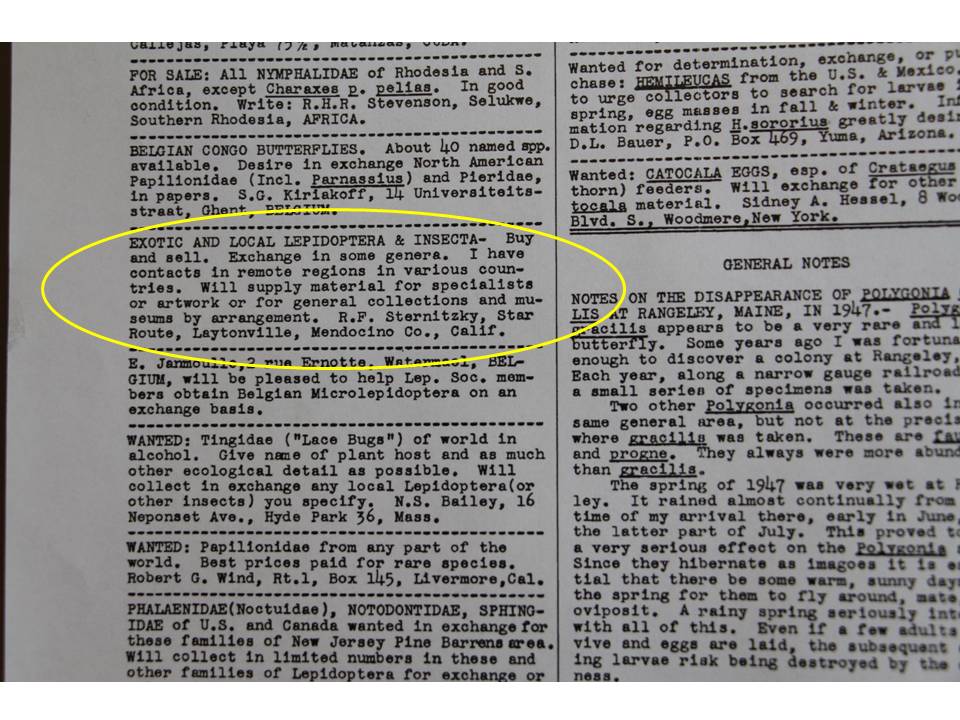

How and why did these specimens arrive in Manitoba? Did the previous owner of the property correspond with R.F. Sternitzky through his ad?

Image: Ad placed by R.F. Sternitzky, in The Lepidopterists’ News, 1948. From The Lepidopterists’ News, May 1948, Vol. II, No. 5 (Edited).