As part of the Manitoba Museum’s entomology collection, we house over 60,000 pinned insects, true bugs, and arachnids. In addition, there are a further ~3000 invertebrates preserved in alcohol, also referred to as “wet” specimens. While the majority of the collection are pinned insects in their adult form, there are also examples of the many and varied life stages that occur prior to the adult form, including egg, larval, nymph, and pupal forms. It is important that a scientific collection contain representatives of these life stages (including males and females of each), as they can and do look very different within any given species.

The Manitoba Museum is a research and collections-based museum whose mandate is to collect and preserve both the natural and human histories of the province for present and future generations. Curators conduct research throughout the province in their respective fields of expertise. Specimens are collected during field seasons and are brought to the museum for preparation and subsequent study. Before specimens can be handled and made accessible for study, they must be prepared to maintain their long-term preservation. Fossils need to be exposed from their matrix, plants need to be dried and mounted, and birds and mammals transformed into skins and skeletons. Insects too, must undergo a preparation process in order to stabilize them for storage, and to make them safer to handle. This is where skill meets a bit of art, and sometimes a little luck!

The Manitoba Museum’s entomology collection represents most of all the very diverse groups and species that occur in Manitoba. Image: © Manitoba Museum

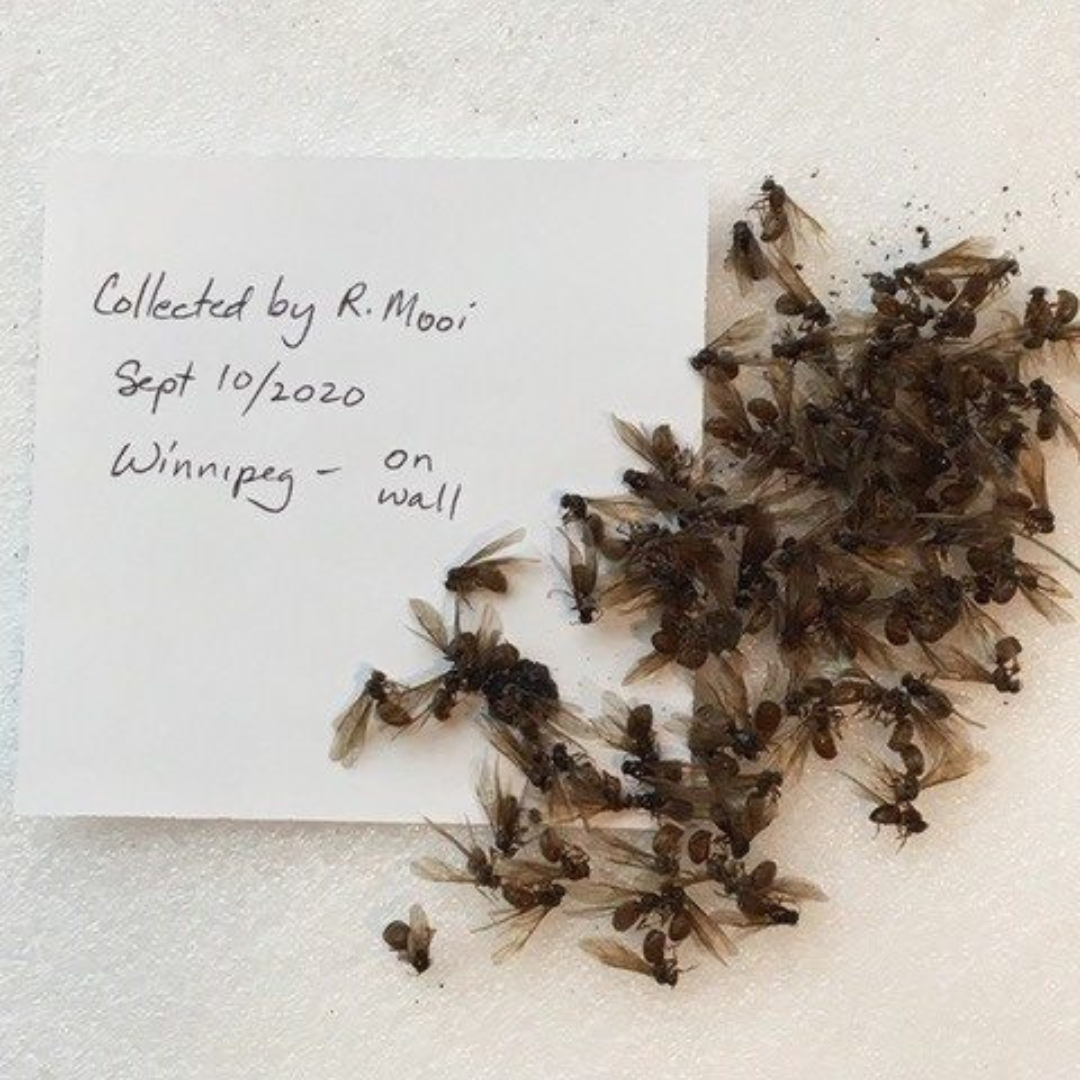

It all starts here – Dr. Randy Mooi, Curator of Zoology, has brought in some dead carpenter ants with collection information. Image: © Manitoba Museum

Once specimens are carefully collected and brought to the museum, a decision must be made on how a particular insect will be preserved. Part of this decision is based on what type of insect (invertebrate) it is, but also how we may want use the specimen afterward. Typically, insect specimens for scientific use are pinned in a traditional manner according to international museum standards where all parts are positioned symmetrically, and anatomy used for identifying characteristics are not obscured. If a specimen will be used for educational purposes, or included in an exhibition in one of our galleries, the pinning is slightly different so that a more life-like pose is achieved. Certain groups or forms, such as a caterpillar (larva), or other worm-like animals, would simply shrivel up if it was pinned, and would not be very recognizable. These types preserve better as a whole body stored in a vial with alcohol as a wet specimen.

I pinned this Confusing Bumblebee (Bombus perplexus) in a life-like pose, as it would naturally be, collecting nectar. Our Diorama Specialist, Deborah Thompson then attached it to a Darkthroat Shootingstar plant model she expertly made. This pair is now installed in the new Prairies Gallery. Image: © Manitoba Museum

When adult insects are collected, they typically become very dry and brittle by the time they are brought into the museum. Handling them is difficult without causing damage, as tiny legs and antennae can easily break off. In order to manipulate and pin them in the correct position, they must first be re-hydrated into a softened state. Plastic containers with good sealing lids are used as a re-hydrating environment. The container is filled with a couple of centimetres of distilled water with some alcohol added to guard against any mould growth. Insect specimens are then placed on top of a piece of rigid foam which is floated within the container. After a few days, the specimens are checked to see if they are pliable enough for the wings and legs to easily be moved. Small flies could be ready in a few days, large beetles with thick exoskeletons and strong ligaments, could take several days.

Insects are placed in a re-hydrating container to soften, and make them pliable for the pinning process. Image: © Manitoba Museum

Once in a softened state, the insect is ready for the pinning process. The insect is gently held while a main pin is inserted through the thorax, just below the base of the forewings, and placed perpendicular to the plane of the body. Special entomology pins are used as they are made of metals that will not corrode when in contact with the insect. They come in different gauges to be used with the varying sizes of insects. A large insect, such as a butterfly, will require a thicker pin for sturdiness, and a very thin gauge pin would be used for smaller insects. Anything even smaller, or extremely fragile is “pointed”. That is, where an insect is too small to have a pin inserted, it is instead carefully glued to the ‘point’ of a small triangle of archival card stock and the main pin is then inserted through the point. This main pin is now the only way the specimen can safely be handled.

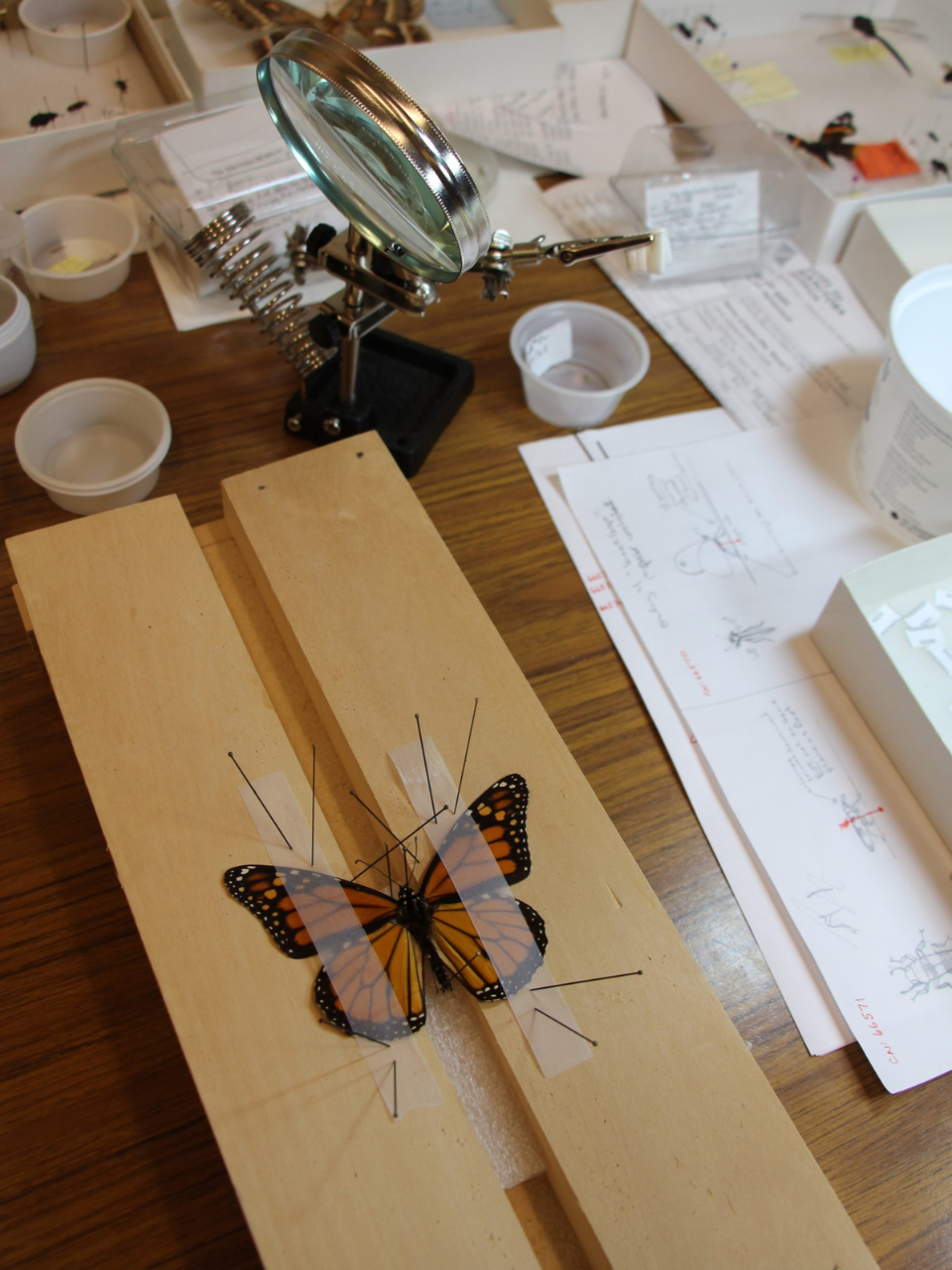

A pinning board is used to properly position a large butterfly specimen. Image: © Manitoba Museum

Numerous support pins are used to position the legs and wings of this fly specimen. Image: © Manitoba Museum

When the main pin has been properly placed, the legs, wings, and antennae must then be positioned. A pinning board made of soft balsa wood or dense foam is used for specimens with large wings such as butterflies, moths, dragonflies, or grasshoppers. It has a trough where the body can be lowered, and the wings can then be spread over the flat surfaces of the boards on either side and supported. Spreading the wings properly is a bit like the game “Twister” for the fingers. Insect wings are incredibly fragile, so carefully coaxing them away from the insect’s body without damaging them takes some practice. Add to that, the wings of Lepidopterans (butterflies and moths) are covered in fine, microscopic scales that aid in flight, waterproofing, and coloration that will break off, like dust, if touched. Forceps are gently used to spread the forewing out from the body on one side, and while holding that in place, the hind wing on the same side, is brought out and positioned. Once both wings on one side are in the proper position, a strip of glassine is placed gently over them. Glassine is a smooth translucent paper that will not abrade the scales of the wings. Pins are then inserted just through the paper and into the underlying pinning board to hold everything in place. This process is then repeated with the wings on the other side. The antennae and legs are then moved into place, slightly away from the body, and support pins are inserted into the board to hold them there. This is done so that the legs do not obscure any important identifying characteristics.

After the insect is pinned into the correct position, it is left to dry. Depending on the size of the insect, it may dry in a few days, larger beetles and dragonflies could take over a week. When it is dried, the positioning pins are very carefully removed and it is now ready for data labels to be attached on the main pin below the specimen. Labels are printed on archival paper and contain all the pertinent data about the specimen such as the identification, who collected the specimen, and when and where it was collected. This data is also entered into our collections management database. As with all specimens in our collections, it is extremely important to keep each specimen together with its data. The data proves that this exact species occurred in this time and place – it’s recorded proof of that biodiversity snapshot of that time. If the data labels ever became separated from its specimen, its intrinsic scientific value is greatly diminished, or completely lost.

The vast diversity of insects of Manitoba’s Boreal Forest is showcased in the Boreal Gallery and contains over 700 invertebrates. Image: © Manitoba Museum/Ian McCausland

Museum collections all over the world apply these same international techniques and standards when preparing and storing specimens for study. This aids in maintaining consistency between museum collections, and have changed very little over the past several hundred years.

Left: Sir Joseph Banks Insect Collection (1743-1820) Image: © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London. Licensed under the Open Government Licence

Right: Present-day insect collection at the Manitoba Museum. Image: © Manitoba Museum